When your husband gets cancelled and you realise you don’t want him anymore

In a new novel, a woman realises – perhaps too late – that she doesn’t love her husband when other people don’t.

Writer Emily Perkins has always been fascinated by the place and role of women, and in this respect Lioness, a first-person novel and her sixth book, is no different. The premise is fascinating. Therese, the childless 50-something protagonist, is married to Trevor, a wealthy, sexual, significantly older man. She begins to question her priorities only when his business dealings are unexpectedly investigated. There are questions about a hotel development in relation to social housing. The council launches an inquiry. Construction halts.

Therese’s response to the puncturing of her husband’s professional probity is as undramatic as their relationship, which features her near-climaxing by visualising “the linen in the soft morning light, his tousled silvery hair, the thick curve of his shoulders, my blonde streaks spread across the pillow” – the sex mature upper north shore couples would have if they had sex with each other: weekend magazine sex, partner-at-a-law-firm sex, with sustainably sourced jasmine and bergamot reed diffusers, a DeLonghi PrimaDonna Elite coffeemaker, and brioche.

A “bourgeois pig” to the bone, Therese revels in her own complacence. Her husband, stepchildren and step-grandchildren pose alongside her in photo shoots for her quarter-of-a-century-old homewares franchise, one pivoting on “an artfully imperfect life, illuminated by pontoon lights, outdoor candles and shafts of golden sun” that “sold the fantasy of time to read poetry and handwrite letters to women who scrambled to make it through the day”.

As Gwyneth Paltrow said while discussing the architecture of her Los Angeles mansion, “I think having spent so much time as an expat in Europe, and really falling in love with Georgian proportions … I really wanted the entryway to feel like its own special room.”

Therese’s marriage, like Paltrow’s special neo-Georgian entryway, is a space for real estate conversations and parties held to make their hosts feel a little less beige.

As she notes, a mixture of people is necessary: “rogue politicians from left and right, philanthropists, architects, civil engineers, property developers, maybe a visiting ambassador. Old satirists and their new wives, gallerists with favourite artists, Trevor’s children, any non-weird city councillors and, occasionally, the Mayor. Wine merchants. Antique dealers. Actors. My hairdresser. A student we sponsored to study jazz performance at Juilliard, who might be persuaded to sing. An old school friend of Trevor’s I privately called Flat Tax because he could talk of nothing else.”

Yet it is the dreary Flat Tax who ushers in that which Therese mistakes for emancipation from the stifling patriarchal suburbia through which she, in linen, drifts.

Even the most tasteful neutrals, however, cannot save her from the righteous left-wing turd discharged “in the middle of the rug I had brought back from a walking trip in Nepal”. People, she realises, no longer like Trevor very much, meaning, clearly, that she can’t, either. Therese observes how quickly her now 70-something husband, once an exciting frequenter of the Venice Biennale and sex parties in Berlin, has been cancelled – why, in some circles, no one “gave a f..k about him. He wasn’t a powerbroker in this room – not even a villain. He was an irrelevant old man. A gnat. The idea was breathtaking.” This recognition causes her “hot shame” to cool to the degree that she is “nothing but a pulse with eyes”.

A flair for description serves to accelerate the weightless narrative’s pace. Praise is carried for decades “like a barley sugar in my handbag”; a “rectangle of blue light” flashes through a pocket as a phone registers a message; childbirth is “a creature inside you fighting to escape”.

The dialogue, too, can whistle like a blade. When Claire, Therese’s only “authentic” friend, describes a cosmetic surgery flub as capitalism ejaculating on her face, Therese is so shocked that she actually laughs. Claire explains the bold statement as the result of having stopped taking antidepressants (“I can finally have orgasms again”). The only reason she remained medicated for so long, Claire adds, was because her children preferred her that way, but now the last one has left home (“It’s great being a mum”).

Claire, who was at university “when women’s studies was something to do”, “knew it was binary and essentialist to associate women with nature” and “reductive to separate nature and culture and technology and to believe that the structures by which she lived were laws of the universe”, but she does so nonetheless because it’s “tiring trying to change the material world, it was so slow, and she had to do something while she was waiting for old men to die”.

Intended, perhaps, to justify Therese’s lack of agency, this paragraph also encapsulates the fundamentally inconsequential denouement. On one level, Lioness is a quiet – neutral, even – rejection of male supremacy; on another, it is a book seemingly composed between other, better, books, something like an extended character study. As if understanding this, Perkins writes, “For a second, I saw this tiny dot of Earth as if from Jupiter, zooming in through space until the colour appeared in the oceans, finding … this speck of city and the cell that was this hospital and the atom inside it that was me. I could see just how little and light my life was.”

Follow Antonella Gambotto-Burke on www.instagram.com/gambottoburke

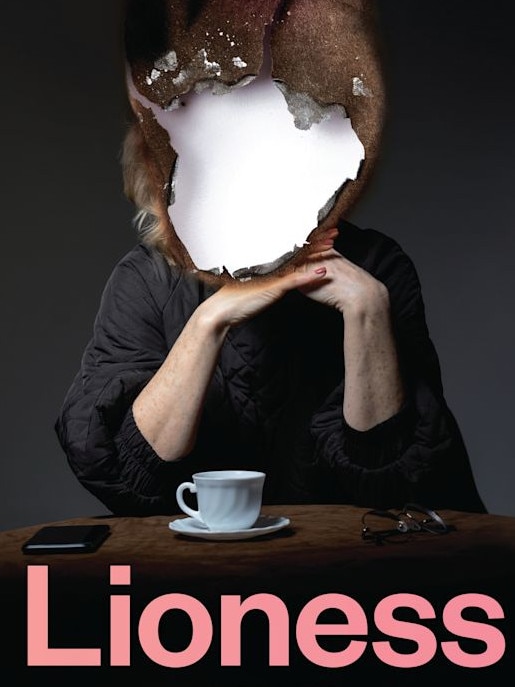

Lioness

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout