When politics and culture collide

THE bloody crossroads, where politics and literature meet, is never particularly bloody in Australia.

THE bloody crossroads, where politics and literature meet, is never particularly bloody in Australia. That is partly because most of our literary writing that attempts to be directly political is so utterly lacking in merit. Nonetheless, politics and culture collide all the time. Politicians try to reflect the culture, and also to mould it.

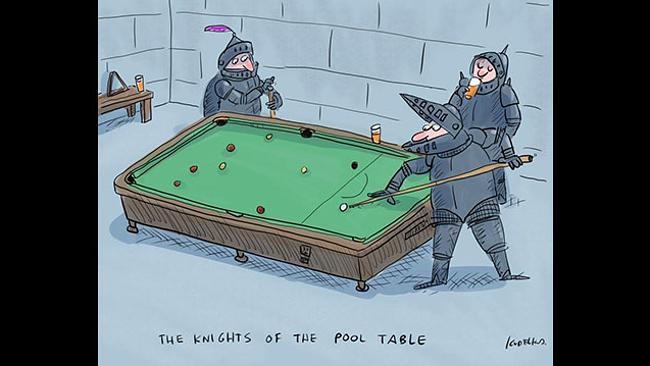

It is no great secret that in a general sense I am an admirer of the Prime Minister; perhaps that’s a minority position but it is by no means an unrespectable one. However, the singular decision he has taken in attempting to shape our culture — the restoration of knights and dames — is the most culturally mistaken of any in his life.

There is always a good deal of sham in national honours. Gerard Henderson hilariously skewers this with his good-hearted persecution on his blog of all those Australians who make a fetish of adding their post-nomials — that is the little bits and pieces of honours bestowed on them by some government committee or other.

Back when we had knighthoods they often made people ridiculous. Barry Humphries for a long time had a wonderfully corrupt and revolting trade union official, Lance Boyle, among his repertoire of fictional characters. I remember attending a Humprhies show back in the years of the Fraser government.

Fraser’s treasurer, Philip Lynch, a perfectly unexceptional politician of reasonable ability and achievement, had allowed himself to be knighted and was thus the rather ridiculous figure of Sir Philip. There was a moment when Lance was talking to his wife who was holidaying in the Boyle beach house, procured of course with corrupt money from Lance’s many union rackets. In style, if not in detail, Lance was based on Norm Gallagher of the Builders’ Labourers Federation, who was a Maoist.

Lance remarks to Mrs Lance that their holiday home is near the Lynch’s home.

“Make yourself known to Lady Lynch,” Lance said, in one of those devastating lines of Humphries satire which has a kind of inexplicable force.

Fraser destroyed an effective anti-Left union leader, Jack Egerton, by giving him a knighthood. Sir Jack became a laughing stock and his career and influence in the labour movement ended.

There was a debate early in Australian life about whether to produce Australian titles. It was rightly thought that this would be ludicrous. But many Australians craved British honours, if not actual titles. Eventually, in 1986, Bob Hawke abolished knighthoods altogether. John Howard didn’t reintroduce them. Australian knighthoods now are not imperial but notionally Australian honours. Yet they are still utterly ridiculous. We have never been as egalitarian in our citizenship as Americans, but the idea, culturally and socially, that no one is inherently superior to anyone else has always been at the heart of Australian life.

It is worth looking to, in my opinion, our greatest prime minister, Alfred Deakin, for guidance. Deakin repeatedly refused a knighthood. He saw Australia as an integral part of the British Empire and he wanted that empire to be a federation of self-governing nations, a strikingly liberal position for the time. He certainly did not want any imperial baubles for himself. He also felt that no foreign government, not even the British government, should have any role in Australian politics.

Deakin also refused an honorary doctorate of laws from Oxford University, in part because Oxford was ultimately an organ of the British government and he didn’t want to be under an obligation to a foreign government. The Oxford vice-chancellor wrote back to Deakin, shocked, saying the degree had only ever been refused once before.

This was in 1887, before Deakin became prime minister. Deakin politely refused an honorary doctorate from Oxford a second time, surely a unique occurrence, and cut off an effort by Cambridge to similarly honour him. He didn’t do this out of hostility. He just felt the system of accepting foreign honours was absurd.

Much later, in retirement, he accepted an honorary doctorate from the University of California because it offered practical benefit to work he was doing for Australia. But he was generally not interested in honours. Deakin remains our most fascinating, complex and literary political leader. His place at the bloody crossroads where politics and literature meet is too little studied.