What to read this week

Notable Books: this week’s reading guide includes books on meteorites, refugees, and song lyrics

This is just fascinating. The author says: “These days, the Heide Museum of Modern Art is a popular place to visit, but in 1969 it was home to John and Sunday Reed, who were close friends of my parents, John Sinclair, and Jean Langley. In February of that year, Jean (my mother) escaped her difficult marriage to live in London, taking my younger sister and me with her.” Jane didn’t return to Australia until she was 15; this book is her mother’s story, told through letters to Sunday. Jane remembers her childhood, dashing about the lovely gardens of what is now the museum. The book includes lovely paintings of flowers, and amazing 1960s photographs. Can’t wait to get stuck in.

I knew absolutely nothing about “the Cranbourne meteorite” before the author wrote to me to tell me he’d written a book about it, which he then sent. It’s a fascinating story: first, a meteorite lands, near Melbourne. It was, at the time, the largest known iron meteorite in the world. It’s believed to have fallen around 1780, and it seems that colonial settlers knew of its existence from around 1836. Indigenous tribes probably saw it first, but it’s on private land when examined, and so, the battle for ownership begins. What a great idea for a book.

Rosemary Lewis is a first-time author at the age of 94. Isn’t that brilliant? Her book features the gorgeous “Portrait of Rosemary” by Cynthia Breusch on the cover. The book is a nonfiction work, based on Rosemary’s many adventures. She fled a suffocating marriage, and restarted her life at the age of 51. I love how she described this: “I had been angry in a dead way for years. I behaved like an efficient martinet. The blackness that oozed from me drove my friends away.” So she upped and moved, developing twin passions for a man, and a house, which she turned into a B&B, in Tasmania. Bravo, Rosemary! A wonderful achievement.

The idea here was to distil, as much as possible, a marvellous selection from David Brooks’s long career, which includes five previous volumes, and The Peanut Vendor, a collection of 48 new poems. Brooks is concerned with the natural world, and the relationship between human and non-human animals. The collection spans 50 years. It has a strong message of justice, and humility, both of which are so often missing from national conversations.

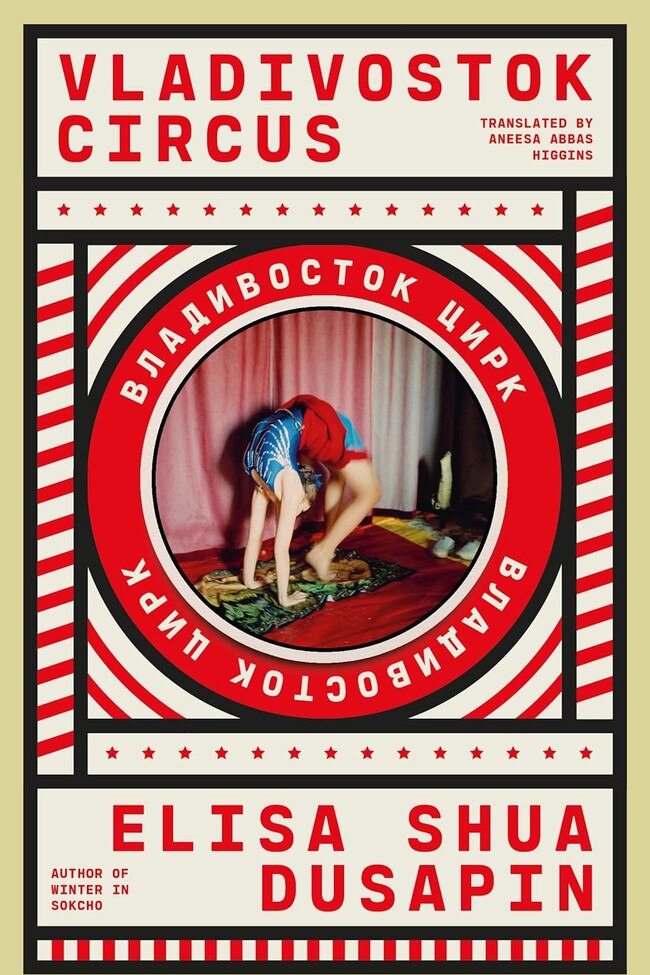

Critics and prize judges swooned over Elisa Shua Dusapin’s first book, Winter in Sokcho. Her new work begins on the opening night of the circus. Our protagonist is there, fresh from fashion school in Geneva, to design the costumes for a trio of artists, who are set to perform a ridiculously dangerous routine on the bars. It’s about artists, learning to trust each other, and the prose is musical.

This felt very close to home for me: it’s about an Australian grandpa, born in the 1920s in Berlin. I had one of those, and I called him Opi, and I loved him dearly. Tessa Scholfield-Peters had one, too. She called him Mutzi. As a teenager, he fled Germany and came to Australia. His parents, who stayed behind, were murdered in Nazi concentration camps. This book is the result of years of painstaking research. A labour of love, for sure, but this man’s story will feel so very real to so many Australians whose families came from Europe before and after the war.

“I’ve built a reputation over the years as a writer of stories but I started out writing songs.” That’s Kazuo Ishiguro, introducing this gorgeous new work. It’s a hardback, with illustrations by Italian cartoonist and illustrator Bianca Bagnarelli, who produces highly regarded comic novels. Inside, you’ll find 16 songs, written by Ishiguro, a Nobel laureate who has also won the Booker Prize, for American singer Stacy Kent. The songs have also been set to music by her composer partner, Jim Tomlinson. What a lovely collaboration. And Ishiguro has written an introduction, which is sublime all by itself.

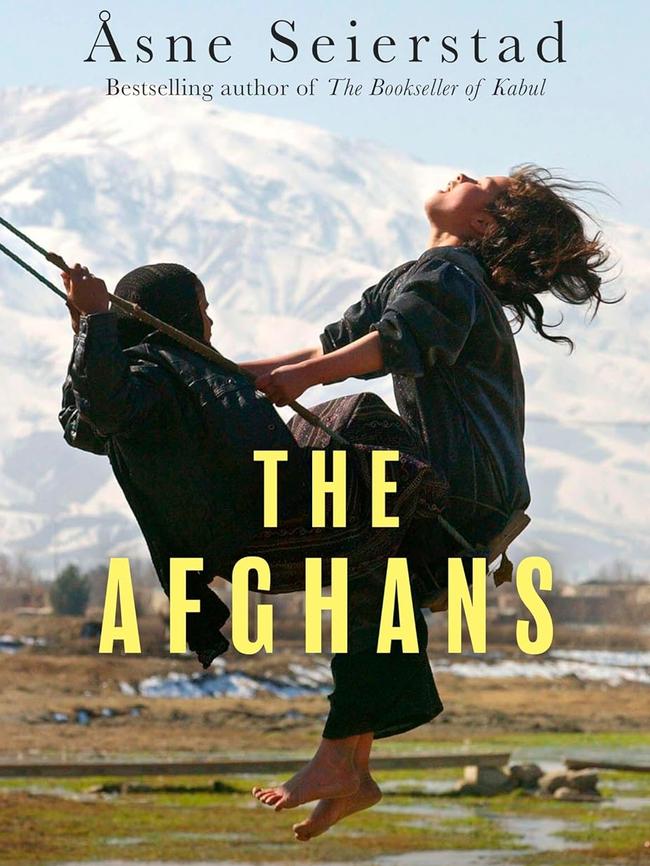

Asne Seierstad wrote the international bestseller The Bookseller of Kabul, which was a study of life in Afghanistan before and after the fall of the Taliban regime in 2001. Twenty years later, she returned to write about life after the Taliban returned. Seierstad tells the story of three women - Jamila, a women’s rights activist; Bashir, a Taliban commander; and Ariana, a law student “who had one semester left when the Taliban came to power”.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout