What kind of mother abandons her children?

Few things seem more unnatural than a mother abandoning her child. It’s enough to send a shiver down your spine. But are we judging women more harshly than men?

Maggie Gyllenhaal’s 2021 film The Lost Daughter, which was based on Elena Ferrante’s novel of the same name, followed a middle-aged woman, Leda (played by Olivia Colman), on a solo holiday in Greece.

She befriends a young mother called Nina (played by Dakota Johnson); in time, she confesses that when she was younger she grew tired of the relentlessness of motherhood and abandoned her children for several years, to have an affair.

Few things seem more unnatural than a mother abandoning her child. It’s enough to send a shiver down your spine.

The Spanish journalist Begona Gomez Urzaiz has felt that same shiver. When faced with stories of absconding mothers, she couldn’t help thinking, “What kind of mother abandons her child?” and hating herself for the judgment that rests within the phrase.

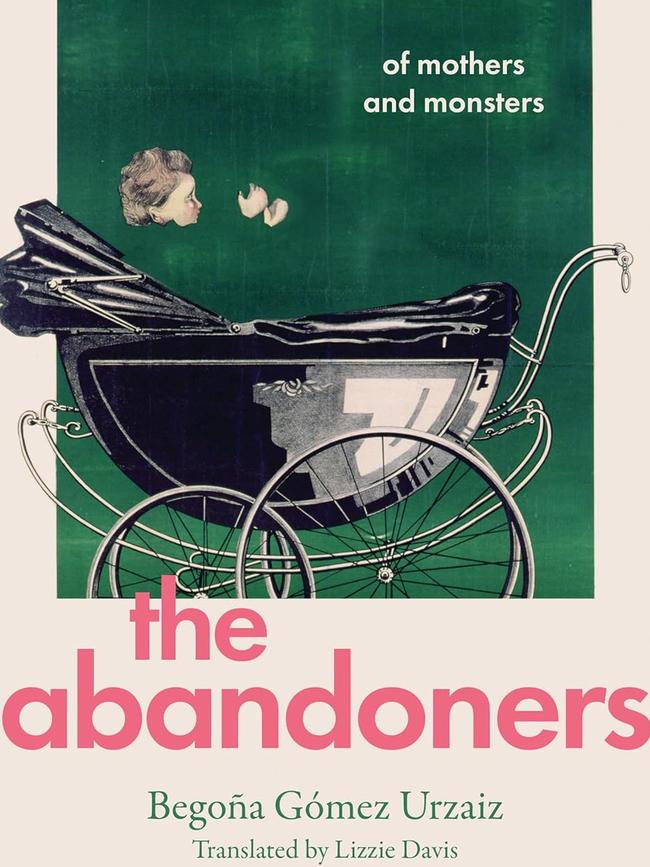

The Abandoners is her way of answering the question. It is a rogues’ gallery of women, real and fictional, whom Gomez Urzaiz classifies as “bad bad mothers” (not the “good bad mothers” who sometimes forget to contribute to the school bake sale); mothers who prioritised their careers, freedom, romance or personal happiness over their children.

Their stories are interspersed with Gomez Urzaiz’s own experiences of motherhood and musings on the sexual inequality that asserts itself the moment you become pregnant.

So we meet Muriel Spark, for instance, in a desperately unhappy marriage with a mentally unwell man and trapped in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). She begged her husband for a divorce, which he refused, so the only valid grounds were adultery or desertion.

“He was not going to desert me, so I deserted him,” Spark wrote. In the process she also deserted her four-year-old son, Robin, who was placed in a convent school.

Spark, of course, went on to become a successful and prolific writer – most famously of The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. But her relationship with Robin never recovered, not even when he followed her to Britain. One of her lovers, observing the interaction between the pair, noted that “Robin is frequently rude and unpleasant to Muriel”, while she “prefers being financially responsible but having no other ties”.

As an adult, Robin sold stories to the press about his mother, leading Spark to respond that her son had “never done anything for me, except for being one big bore”. When she died in 2006, Spark didn’t leave Robin a penny.

Doris Lessing was even less apologetic. She too had abandoned her family in Rhodesia to escape an unhappy marriage, leaving behind three-year-old John and one-year-old Jean. She was 21 at the time.

Asked about them in an interview, Lessing snapped: “The truth is people are angry because I didn’t go on at length about how terrible I was to walk out on my children ... On the contrary, I’m very proud of myself that I had the guts to do it.”

But why? For Lessing, it was simple: “There is nothing more boring for an intelligent woman than to spend endless amounts of time with small children.” Putting her talent first had its rewards, not least the Nobel prize for literature, which Lessing won at the age of 87. But although Gomez Urzaiz does her very best to extend sympathy, or at least ambivalence to Lessing, you come away from the chapter feeling that she was a pretty unpleasant individual.

Does it matter that Lessing was a bad mother? Should that affect how we think about her work? Does it make The Golden Notebook any less great? Should we be donating to Barnardo’s every time we read The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie?

Of course not, Gomez Urzaiz concludes, rightly. But this prompts the question: what is the purpose of her book? Gomez Urzaiz skips lightly from Spark and Lessing to a whole host of negligent mums. There is the actor Ingrid Bergman who left her daughter, Pia, behind to begin a relationship with the director Roberto Rossellini, suffering the “daily sadness” of separation in exchange for his love.

Then come the “momfluencers”, women who make a living from posting content about their children. One, Myka Stauffer, made huge sums out of her experience adopting an Asian child only to give him up when it was discovered that he was autistic. There are even a few fictional characters: Anna Karenina and Emma Bovary are among the literary mothers put in the dock for their mothering failures.

The stories are fascinating, but Gomez Urzaiz offers little analysis beyond comparisons with her own life (she sometimes feels fed up with her two young children too).

Such a painful and sensitive topic requires an argument to tie together these sad tales – and one a bit stronger than “It’s hard to be a mother sometimes”. It would be like writing a book about refugees, then complaining that you miss your family in Shropshire since moving to London for a job – not really the same thing and not that helpful.

This is only compounded by Gomez Urzaiz’s truly moving final chapter, which consists of interviews with women who were forced to leave behind their children in developing countries because they couldn’t afford to support them. These women make up “98 per cent” of the mothers who abandon their children, Gomez Urzaiz estimates.

One woman left her daughter in Nicaragua to become a nanny in Spain, and laments that “the love you have, you give it to these other children”. Another had to leave in the middle of the night because she couldn’t bear to say goodbye. She worries that when she eventually returns to her daughter, “she won’t be able to sleep, afraid I’ll leave her again in the night”.

It’s an incredibly upsetting series of anonymous confessions, one that illuminates the disparity between these women and the writers and actors Uzaiz profiles earlier. In fact, it undermines Uzaiz’s entire project. For the bulk of the book, her readers will probably strain to feel sympathy for Lessing and co. And then we’re presented with these utterly devastated women with no choice but to leave their children behind. For me, it obliterated any shred of sympathy I had for the former.

But my ultimate feeling was one of unease, not dissimilar to the shiver I got from watching The Lost Daughter.

Why is Uzaiz so intent on collecting these women – “my abandoners”, she calls them – in this bizarre but intriguing book? Why does she want to compare their sins and struggles? We live in a confessional age, but some sad stories, I think, are best left to sink into the past while the victims lick their wounds.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout