Was bad boy photographer Helmut Newton a sexist or feminist, asks new film The Bad and the Beautiful

A new documentary asks whether photographer Helmut Newton – famous for his female nudes – championed women or just objectified them.

On one side of a photographic diptych titled Evi the Cop, Beverly Hills, a woman is dressed as a Los Angeles police officer. She is equipped with a gun belt, truncheon, oversized sunglasses and a stern expression, while her arms are tensed as if ready to grab her weapons. In the adjoining panel, Evi adopts the same defensive pose and official uniform – except that she is naked from the waist down.

In another photograph, related to a Pina Bausch ballet, the bare buttocks and elegantly positioned legs of a headless ballerina protrude from the mouth of a huge crocodile. And in a cover shot image for German magazine Stern, a naked black woman – the Jamaican-American model and disco diva Grace Jones – is crouching, naked and smiling, despite the thick chains wrapped around her ankles …

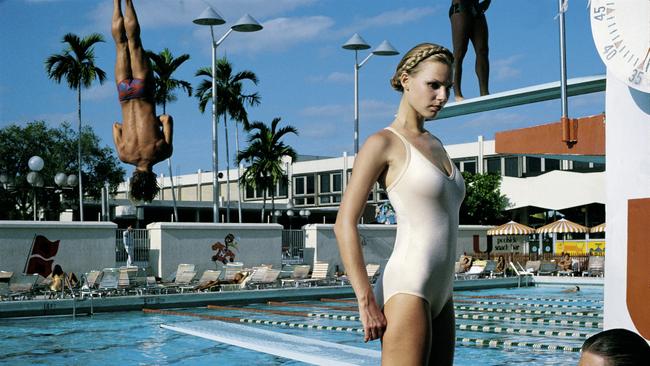

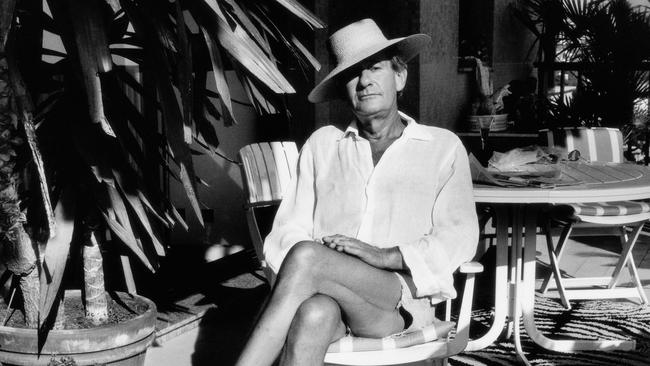

Welcome to the insistently transgressive oeuvre of German-Australian provocateur Helmut Newton, who spent 17 years in this country before he evolved into one of the 20th century’s most influential fashion and celebrity photographers, cannily blending art, commerce and “porno-chic”.

Christened the king of kink, Newton produced erotically-charged nudes and other provocative images that were celebrated in high-end art books (1999’s Sumo weighed in at 35 kilos), gallery exhibitions in venues including London’s The Barbican and Berlin’s Neue National Galerie and a string of glamorous magazine assignments for Vogue, Vanity Fair and Stern. From the 1960s to the early 2000s, Newton trained his lens on top-drawer celebrities and public figures including Raquel Welch, Catherine Deneuve, David Bowie, Elizabeth Taylor, Nicole Kidman and former German Chancellor Gerhard Schroder.

However, the photographer, who died in 2004, is most remembered for his photographs of beautiful, Amazonian women, often naked but for their skyscraper heels. Newton frequently introduced attention-seeking props to these and other images, such as a saddle placed on the back of a kneeling woman, or a model wearing million-dollar Bulgari jewels while ripping apart a strangely sexualised roast chicken.

Now, a new documentary asks Newton’s famous female muses, models and collaborators whether he was a feminist – as he claimed – or a career chauvinist. Helmut Newton: The Bad and The Beautiful is set to be unveiled in Australia at next month’s Melbourne International Film Festival and at cinemas later this year. It features extensive interviews with June Newton – Helmut’s Australian wife, who died recently; legendary Vogue editor Anna Wintour; and women who posed for him including Isabella Rossellini, Charlotte Rampling, Claudia Schiffer, Marianne Faithfull and Jones.

With a playfulness Newton would have admired, Jones declares: “He was a little bit (of a) perv but so am I, so it’s okay.” The singer says he “told stories” through his nude portraits of women, including her. “It was never vulgar,” she insists, although she reveals he initially didn’t want to photograph her, claiming her breasts were too small.

In the late 1970s, his Stern cover photograph of Jones naked and in chains provoked uproar and accusations of sexism and racism. Jones didn’t see it that way. “I never felt that at all,” she says, arguing that the contentious image reflected German society’s sexist and racist undercurrents.

The documentary is directed by German filmmaker Gero von Boehm. Asked for his verdict on Newton’s alleged sexism, von Boehm tells Review: “I’m not sure if a documentary should have a verdict … It’s up to the audience to define it for themselves.” However, he goes on to say: “Helmut Newton definitely was not a sexist. On the contrary, in many of his pictures he wanted to show us how strong women are.”

The director has studied thousands of pictures held by Newton’s estate and concluded the photographer admired women for their beauty and emotional intelligence. “Of course, some of his photos certainly provoke a male gaze, male fantasies,” he concedes, “but that is natural.”

As for Newton’s claim to be a feminist, von Boehm says, “one could ask if that’s the right word, I admit, but it was not cynical”. He mentions the Newton diptych Dressed and Naked.

In one image, a quartet of models strike catwalk poses in couture outfits, and in its twinned image, they adopt identical poses and are nude, “as if a magician had taken their clothes away. It’s not only a gag, he wants to tell us that women are strong even without those expensive clothes.”

Speaking from Germany, von Boehm explains that his biopic aims to “give carte blanche” to the women who worked with Newton to speak about him. He says mostly male curators and editors have done this but “rarely women, because obviously they were never asked. They gave wonderful answers. After so many years, the memories were so sharp and precise.”

Known for his aesthetic brilliance and calculated perversity, Newton, a Jewish refugee who escaped from the Nazis in 1938, brought fetishist and sadomasochistic subtexts to mainstream commercial photography. He describes himself in the film as Wintour’s “favourite old naughty boy” and boasts: “I am a professional voyeur … I am interested in face, breast, legs.”

He insisted his super-sized nudes depicted their subjects as self-confident and haughty – looking down on the men watching them. Feminists have disputed this and accused him of objectifying his models and pushing mass market photography towards pornography. The Bad and the Beautiful includes footage from a television interview in which renowned feminist Susan Sontag tells Newton his photographs are “very misogynous”.

Newton replies: “I love women. There is nothing I love more.”

Sontag counters smoothly: “The master adores his slave. The executioner loves his victim.”

Blue Velvet actor Rossellini is also a feminist, and she argues that Newton’s images of women exposed western society’s “machismo”: how men’s attraction to women could make them feel weak and threatened; an attitude of “I like you. Damn you.”

Wintour says engaging Newton for a Vogue assignment meant “you obviously weren’t going to receive a pretty girl on a beach”. She acknowledges his work “sometimes upsets people”. “I personally considered it necessary,’’ she says, adding that his images were more dangerous than those of other celebrated fashion photographers Irving Penn and Richard Avedon.

Newton once said “I love vulgarity. I am very attracted by bad taste”, and von Boehm says another objective of his film is to show “how important a certain amount of provocation is in photography, in the arts”. He feels that because of political correctness, photography has become too tame.

“I would be happy if the documentary encourages young photographers and artists to go to the limits, to have the courage to be a little more anarchistic and not be politically correct all the time,” he says. He reckons the threat posed by cancel culture is “terrible. We need freedom of art. We need freedom of expression.”

June Newton, a former Australian theatre actor who married Helmut in 1948, plays a prominent part in the film. She passed away earlier this year in Monaco, aged 97, and von Boehm knew her well.

June says in the film that Helmut’s photography was “a passion”, “obsession” and buffer between him and the world; as the couple aged and underwent various operations, he always took his camera to hospital. “It is a protection,” says June, who, working under the pseudonym Alice Springs, was a successful photographer in her own right.

According to von Boehm, Australia remained important to the couple, who met, married and worked here before moving to London and Paris in the late 1950s: “June remained Australian to the very end,” he says.

“Wonderful memories – they both started their careers there. They left because they wanted to have an international career. They were always talking about Australia.

“Australia was a symbol for their symbiosis. Helmut was the playful boy from Berlin with thousands of ideas, and June gave him the structure he needed in life. She edited his books and was curator of his exhibitions; she was choosing the models often.”

Even so, the film suggests their relationship could be rocky, given he was hanging out with young, beautiful women. Von Boehm says of this: “I asked him about it and he always said, ‘Business is business and schnapps is schnapps’. He separated his private life strictly from his professional life. He would never have touched a model, never.”

Newton says on camera that he didn’t mind causing others “pain” in order to get a memorable photo. We see one unsettling photo shoot with a young, naked model clambering onto the shoulders of a male model in a scuba-diving suit and goggles. Later Newton says jokingly to the male model: “If you get a hard on all the better; you’ll get more money.” Such remarks put a question mark over Newton’s claim to be a feminist.

The Bad and The Beautiful is an authorised bio-pic, made with the co-operation of Newton’s estate. Von Boehm, a German TV presenter who made his first documentary about Newton in 2002, was given access to a trove of images, notebooks, contact sheets, and intimate footage of Newton shot by June. He says he exercised “complete” editorial freedom: “Nobody interfered ever.”

The documentary candidly explores how Newton’s images of Amazonian women with athletic, almost sculptural bodies, were inspired by the work of Hitler’s favourite filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl. This seems counterintuitive, when you consider Newton and his Jewish family fled Nazi Germany in 1938.

Von Boehm explains that the Nazis exploited glamorous images reflecting “the cult of the body”, and Newton, then a budding photographer living in Germany, was “interested by that visual world. In the film he admits that for the first time. Up to the end (of his career) his playing with shadows has hints of Riefenstahl … He admired her artistic achievements, and hated her at the same time because she was a very important part of the Nazi regime.’’

Newton’s innovative use of light and shadow and his melding of shock tactics, fashion photography and celebrity portraiture saw his works collected by leading museums and galleries, among them London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, Paris’s Bibliothèque Nationale, New York’s Museum of Modern Art and the National Gallery of Victoria.

The photographer was born in Germany in 1920 into a wealthy Jewish family that owned a button factory. He says his mother encouraged his interest in photography while his father was horrified by it. Nonetheless, when he finished school, Newton was apprenticed to the pioneering Berlin photographer Yva (Else Simon), who is thought to have later perished in a Nazi concentration camp.

In 1938, aged 18, Newton left Nazi Germany, and eventually made his way to Australia via Asia. From 1940 to 1945 he served in the Australian Army, and after settling in Sydney, he met and married June. He remained in Australia for 17 years, setting up a studio in Melbourne and working as a fashion photographer, before he was drawn overseas to work for the British, French and Australian editions of Vogue, and other magazines.

In their later years, the couple split their time between Monaco and Los Angeles. Before he died in 2004 following a car crash in Los Angeles, Newton set up the Helmut Newton Foundation in Berlin. The Foundation exhibits his and June’s images “in dialogue” with other photographers’ work. In a poignant irony, it’s housed in a building neighbouring the railway station from which the photographer escaped from Nazi Germany soon after Kristallnacht.

Newton’s oeuvre, says von Boehm, will continue to spark spirited debate: “That’s good because art should be the subject of debate and we are now entering an era where debate is no longer really possible because everything is too prudish, too politically correct. He contributed a lot to the history of photography. He changed fashion photography completely at the end of the 1960s and 1970s.” He shook things up, says the filmmaker, because “he was playful enough, he was courageous enough … and a little bit anarchistic. And the magazines loved that.”

Helmut Newton: The Bad and The Beautiful will screen at Melbourne International Film Festival, held in August 5-22. It will be released in cinemas later this year.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout