Wake in Fright: a vision of a grotesque, untamed and merciless culture

Outback thriller Wake in Fright was a commercial disaster when it was first released, but 50 years on it’s firmly regarded as a classic.

It’s revered by critics as one of the greatest Australian films of all time, a disturbing precursor to an era now widely described as Australia’s film renaissance. But when Wake in Fright first screened in Australian cinemas half a century ago, audiences were shocked. Here was a vision of a grotesque, untamed and merciless culture, one which spurned the quaint motifs of traditional bush life and embraced the archaic barbarity at the heart of the Australian outback.

Wake in Fright took all that was sacred about the outback and turned it on its head. It was, as one contemporary critic noted, “the most savage comment on Australia ever put on film”.

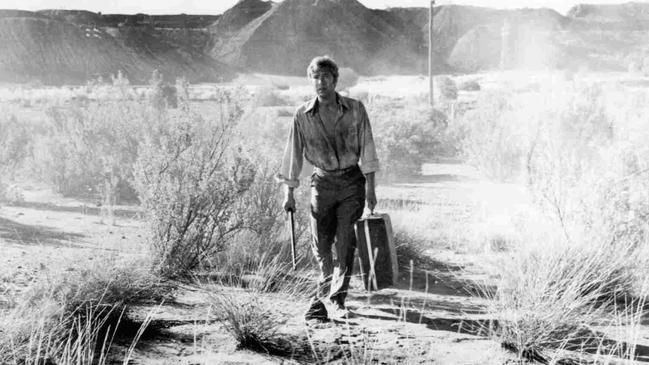

Based on Kenneth Cook’s 1961 novel, Wake in Fright tells the story of a few days in the life of teacher John Grant (Gary Bond), who finds himself marooned in the remote town of Tiboonda until he can serve out his bond to the education department.

Grant is a city-dweller and despises everything about the outback: its heat, its isolation and its people.

At the end of term, Grant plans a trip to Sydney to meet his girlfriend, but before he can fly east, he must first stop over at the remote mining town Bundanyabba — known as The Yabba.

The night before his departure, Grant meets the town’s policeman, Jock Crawford — played by a barrel-chested Chips Rafferty in his final big-screen performance. After some heavy drinking, Grant encounters Doc Tydon (Donald Pleasance), a chilling and sepulchral creature, a kind of Iago of the outback, whose sole purpose is to drink, manipulate and play fool to his benighted masters.

Grant tries his luck playing two-up, hoping to win enough money to pay off his bond, but by the end of the night he loses everything. Drunk and penurious, Grant is stranded. Now The Yabba has him.

In desperation, he turns to the dim-witted drunk, Tim Hynes (Al Thomas), who invites him back to his house for further liquid refreshment. Soon enough they’re joined by local miners Dick (Jack Thompson) and Joe (Peter Whittle) and later by Tydon himself. The five consume enough beer to fill a small aquarium, and the night descends into a blur of sexual misadventure and homoerotic tension.

The film’s climatic sequence comes as Grant joins a drunken kangaroo shoot, which, 50 years on, has lost none of its savagery or vividness.

Even as late as 1984, when the film first appeared on late-night television, Wake in Fright’s reputation as a cult classic was by no means assured. While it drew favourable reviews, commercially it was a disaster. In Britain the film flopped, and in America no one showed up. “I find the film excites disgust — period,” wrote English critic Dilys Powell, “yet if that is what you want in a film, testicles to you.”

It was the French who championed the film first. Following a successful premiere at Cannes, Wake in Fright enjoyed a 10-month run at a Paris cinema, under the title Reveil dans la terreur. But while the French seemed to embrace the film’s sense of existential dread and anomie, its tepid reception elsewhere condemned it to obscurity.

But why for so long?

For acting legend Jack Thompson, the answer is simple enough: “I honestly don’t think Australians were prepared for the shock of it,” he tells Review. “We’d grown accustomed to this mythology that we were really just good blokes — ‘you beauty, mate’ and ‘up the digger’ — and the film presented us, for the first time, in a way that was direct, raw and intimate.”

In Thompson’s view, the film came too close to the bone, striking at the very heart of the cultural cringe.

“We had a view of ourselves as a polite British outpost, and when people saw the depiction of the Australian ethos as it was presented in Wake in Fright they were gobsmacked … People were coming out saying, ‘That isn’t what we’re like, that isn’t us’.

“Many of the people who walked out would’ve experienced some of that nightmare themselves and, in fact, recognised it … they didn’t want to believe that there might be a strong element of who we are.”

Thompson, 80, who made his film debut in Wake in Fright, recalls the shooting as formative: “I remember one occasion Donald Pleasance was standing next to myself, Peter Whittle and Gary Bond while the three of us younger actors were discussing the differences between stage and film acting. Pleasance was listening in. He walked off and then came up behind me and whispered: ‘Feed the camera, Jack … just feed the camera.’ And I have never forgotten that advice.”

After more than 45 films, the veteran actor still considers Wake in Fright as top of the heap: “I consider it the spark that lit the fire of the Australian film renaissance.”

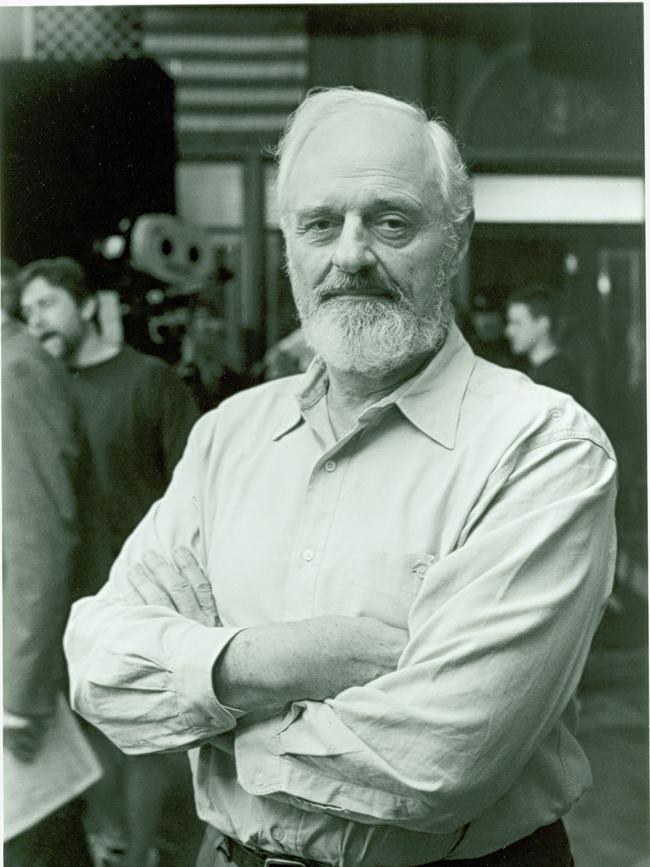

Yet despite its status as a quintessentially Australian film, Wake in Fright brought an international flavour. Alongside Pleasance, there was Anglo-Jamaican writer Evan Jones, Anglo-Norwegian producer George Willoughby and, of course, its Canadian director Ted Kotcheff.

According to Thompson, Kotcheff’s perspective was the clincher. “The British thought they really knew us, but Kotcheff saw the outback from his own Canadian perspective … it made it real and authentic, not cliched in a way that might have happened with a British director.”

By any standards, Kotcheff’s outback reconnaissance was impressive.

“Initially I was worried about making a film depicting a world whose customs and mores I knew very little about,” he admits in his memoir, Director’s Cut. But after arriving in Broken Hill, he began to recognise a world not unlike his own.

For months, Kotcheff traversed the red interior in search of the perfect location. He befriended local journalists and undertook boozy drinking expeditions of his own.

“I understood and admired the men of the outback: their fortitude, their camaraderie, their generosity, their support of each other.”

While Kotcheff’s film remains remarkably faithful to Cook’s text, it deviates at important points, especially when it comes to describing the men of The Yabba. Whereas Cook’s contempt is thinly veiled, Kotcheff’s portrait suggests a crew of misunderstood larrikins, victims of place and circumstance.

In the case of Grant, a similar tension between text and film holds true. For Kotcheff, he is an enlightened figure, a shiny beacon amid a cultural wasteland. In Cook’s eyes, however, Grant is a churlish snob, tainted by hubris and certainly no better than his outback acquaintances.

To the very last detail, Kotcheff was determined to present the outback in its most authentic form. Thus, cool colours were forbidden, faux Aussie accents were out and, where possible, locals would be engaged as extras rather than trained actors. Hundreds of sterilised flies were sent in from a Sydney lab to reinforce the film’s sense of heat and discomfort.

The intense feeling of claustrophobia amid limitless space was essential. For Kotcheff, the landscape was imbued with a sinister life force of its own. It stared back at you, drawing you in with prurient eyes, making Grant’s downfall seem almost inevitable.

When it came to shooting the notorious kangaroo hunt, Kotcheff knew there was no escaping it: “The scene was critically important, but I was not going to kill or harm kangaroos to realise it.” After persuading two hunters to join a late-night shoot, Kotcheff decided he would film the hunt as if he was “shooting a documentary”.

“It was a harrowing experience. We rode standing in the bed of one of the trucks with a camera mounted on top of the cabin next to the spotlight. For the first five hours, they were incredible marksmen. But then they were missing everything. I leaned over to look into the truck below to see what was happening. On the dashboard was a half-empty bottle of whiskey.”

By the late 1990s, Wake in Fright had already gained a reputation as a lost classic. For decades the negatives were thought missing, perhaps even destroyed. It wasn’t until 1994, when the film’s editor, Anthony Buckley, took up the challenge, that the hunt gathered serious momentum.

Realising its cultural significance, Buckley, 84, embarked on a decade-long search for the film. “I assumed the negatives were in a laboratory somewhere in London or Dublin,” Buckley tells Review. “And it wasn’t until I got in touch with UA in Pinewood, who said they’d lost the film rights, that I really began to worry it was gone forever.”

But in 2000 Buckley struck gold after an American contact delivered a breakthrough lead, suggesting the negatives might be buried in a film vault in Pittsburgh.

“I was put in contact with Harvey Rappaport from CBS. He was confused about all the fuss surrounding this obscure Australian film and after a couple of years of back and forth he eventually – probably to get rid of me – headed to Pittsburgh himself to search for the negatives.”

It was there that the negatives were finally uncovered among a sea of barrels marked “For Destruction”.

“It was literally on the cusp of oblivion,” says Buckley, “and there they were, after all that time, in can after can marked Outback.” However, the journey to full restoration was far from over. In 2006, the negatives were delivered to Anthos Simon of Deluxe-Atlab.

“They were in a horrible state,” Simon explains. “If it was restored through a simple preservation process, where you take the negatives and duplicate them, it would’ve failed. They were delicate and damaged. I was worried they’d break during the scanning process.”

The only option, Simon argued, was to undertake a full digital restoration, wherein the film would be restored frame by frame. “If you think there are 24 frames per second, and we had more than 130,000 frames to work through … it was a monumental task.”

When Wake in Fright was re-released in 2009 it was hailed as a triumph. In Sydney, the red carpet was rolled out and the stars returned, almost four decades on, to celebrate its restoration. Audiences flocked to the cinema to catch a glimpse of the “lost classic”.

News of its rescue so impressed the cognoscenti of The Cannes Film Festival they requested a print of their own, leading them to declare Wake in Fright a Cannes Classic.

Now a new generation has since embraced the film, prompting a fresh edition of the novel and inspiring a play and a 2017 miniseries reworked for a contemporary audience. But for Buckley nothing comes close to the original – anything less is pastiche.

Asked what he thinks of the recent adaptations, he offers a wry grin: “I haven’t seen either,” he confesses. “But then why would you bother remaking something like Casablanca? Pointless.”

It’s pleasing to note that, half a century on, the beer-soaked bowels of the Bundanyabba have lost none of its potency – or its menace. Somewhere, out in the shimmering haze, the Yabba is still calling: “how about another beer, mate?”

Wake in Fright is available for streaming on Stan, YouTube and Google Play.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout