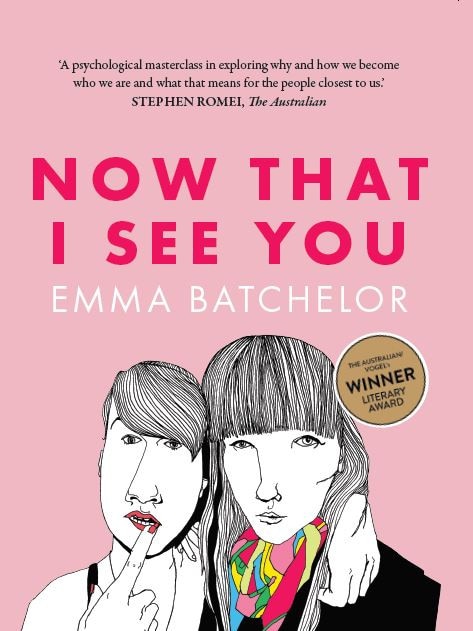

Vogel-winning tale of love and transgenderism brave and bold

Through all the twists and turns of its narrative, one constant in Emma Batchelor’s debut novel is the phrase “I love you”.

Emma Batchelor’s debut novel, winner of this year’s The Australian/Vogel’s Literary Award, overflows with avowals. Through all the twists and turns of its narrative – a story built from real journal entries and emails kept by the author over a period of years – one constant is the phrase “I love you”.

Such repetition brings to mind a passage in Maggie Nelson’s The Argonautsfrom 2016. In that earlier autofiction about relationships, Nelson sends a passage from French writer Roland Barthes (about the Argo, the mythical ship in which Jason sought the Golden Fleece) to a man who makes her feel vulnerable because she has just admitted her love for him.

“Barthes describes how the subject who utters the phrase ‘I love you’ is like ‘the Argonaut renewing his ship during its voyage without changing its name’. Just as the Argo’s parts may be replaced over time but the boat is still called the Argo, whenever the lover utters the phrase ‘I love you’, its meaning must be renewed by each use, as ‘the very task of love and of language is to give to one and the same phrase inflections which will be forever new’.”

Now That I See Youis a novel, based on events from the author’s life, in which love is challenged to keep renewing itself within a relationship that is fluid in essence, confronted by change and fraught with potential for misunderstanding.

To clarify: when Emma gets home from work one ordinary afternoon, her rangy, live-in, jeans-and-sneakers partner, Jess, announces he likes to dress as a woman. As the days and weeks go on, his admission takes on a more profound cast. It is not just that he likes to cross-dress; he feels himself to be a woman. After five years spent in a relationship with Emma and pushing this knowledge to the side, Jess accepts he is transgender.

In the small but brilliant canon of books about trans experience – from Virginia Woolf’s Orlandoto Manuel Puig’s Kiss of the Spider Woman, Jan Morris’s memoir, Conundrumto Thomas Page McBee’s boxing autobiography, Amateur – it is the person undergoing a transition between genders who is the understandable focus.

What makes Batchelor’s book different – and valuably so – is that it concentrates on the experience of the trans person’s partner: the one left beached by their more settled sense of identity. What does it mean, the novel asks, to have your partner change in this way? Is it the end of your relationship or the start of something new?

To begin with, Now That I See You narrates its author’s own confusion. The journal form is ideal in this regard – it allows sudden expansions in awareness to be aired and examined, domestic hypotheses to be tested on the page. When Jess first wears women’s clothes or makeup. When “they” request a revision of pronouns. When they tell their mum. All these radical firsts flow through Emma’s private conversations with herself.

Emma’s response is both impeccable and messily human. She is shocked but accepting. She reads all the literature on the subject she can get her hands on, respects Jess’s desperate sense of unsettlement, shading into outright depression; offers her unstinting love and support. The author absorbs the full implications of Jess’s altered circumstance like so many waves of radiation from a nuclear blast.

Interspersed with the journal entries, however, are emails to Jess, which can be angrier and more plaintive. Emma has always been the more emotionally lucid partner: Jess, who she tells us is on the mild end of the autism spectrum, is often closed, silent, sullen. Much of the drama of the narrative concerns how elusive this other presence can be: a person who has disappeared into the ambiguity of a new pronoun.

But there is also the sense, at first imperceptible to Emma but ever clearer to the reader, that her love for Jess is damaging. Stendhal, that enduring analyst of the ways on which we become attached to one another, wrote of the act of crystallisation: the moment of tender delusion when a blow to the integrity of a relationship only lodges it more firmly in the heart of the more loving one.

As Jess begins their journey towards being “Jesse” and so away from their relationship as it was originally conceived, Emma sees new reasons to keep them close by. Just as an ordinary twig left down a salt mine is, in Stendhal’s example, transformed into something magical and glittering, so too has Jess’s shift furnished new and remarkable reasons to cleave to them.

Now That I See You is, then, the story of a slow disenchantment from one kind of love – a grief for lost affection rendered in terms so plain and unadorned that the reader longs to throw a blanket over the pages and put a kettle on for them – and the emergence of love of a new and different sort.

The protocols of self-disclosure demanded by autofiction mark Batchelor as a woman of bravery and uncommon decency – that she includes moments in which she fails in these regards only makes her more so. Most important, though, is the author’s refusal of easy answers or pat responses that mark traditional, which is to say binary, thinking about transgenderism. This novel stakes out territory in the grey areas in between.

Geordie Williamson is chief literary critic of The Australian.