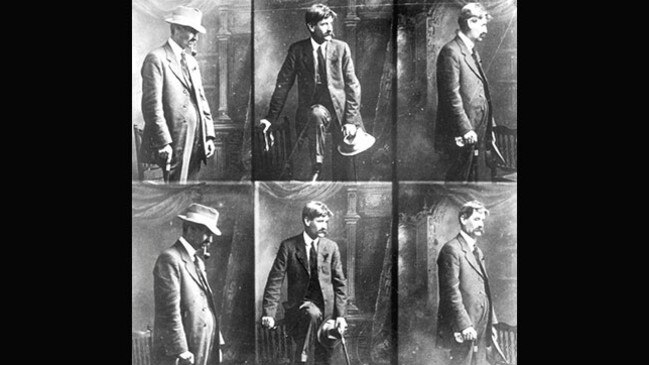

Untold Story of Bertha and Henry Lawson; Mates that sustained him

Henry Lawson has been a bone of contention for biographers. Two new books look at his long-suffering wife, and mates.

How to approach a biography subject who is a national icon, whose work is canonical? Since his death, Henry Lawson has been a bone of contention for various biographers. The most recent interesting approaches have been to consider other aspects of the story, as with Brian Matthews’s Louisa (1987), about Lawson’s gifted and formidable mother. In two new books, Lawson is considered as part of a dual biography.

In A Wife’s Heart, Kerrie Davies explores Henry and Bertha Lawson’s marriage, juxtaposed with her own memoir of single motherhood. In Mates, Gregory Bryan writes parallel lives, of Lawson and his friend bush poet Jim Gordon (pseudonym Grahame, so as not to be confused with Adam Lindsay). Although Gordon is now largely forgotten, Lawson considered him the better writer.

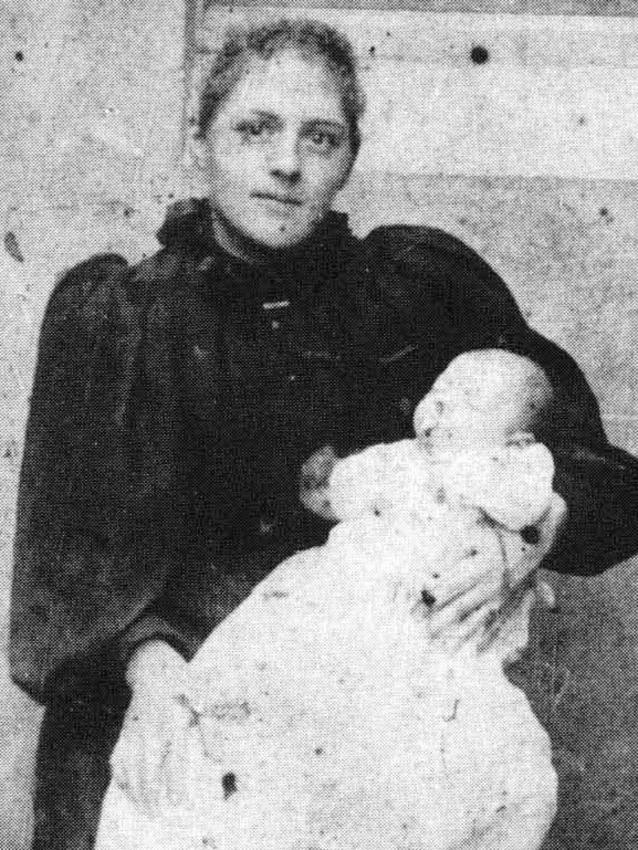

To Davies first, and Bertha, a woman too conveniently dismissed as a she-devil who destroyed a great Australian author. Her family were socialist booksellers and her sister married Jack Lang. Bertha was very young when she married, soon a child with children. Little about her early photographs suggests strength, or that she would survive mental illness and a spectacularly unhappy marriage.

In writing this book, Davies fills a gap in the Lawson story. It is a contested space, Lawson having his partisans. Several acted as if they had proprietary rights on his life, from Mary Gilmore to Colin Roderick.

In making Lawson an icon of Australian letters, some gifted women were overshadowed, including Miles Franklin and Barbara Baynton, arguably his superior. Lawson’s womenfolk fared even worse. Matthews’s Louisa did take issue with the general misogyny, much originating with Lawson himself. It is only now that Bertha gains a similar advocate at book-length.

In part Bertha’s occlusion seems less than that she had active enemies but that others sought to protect her. Her records from an English insane asylum were under embargo, as were the papers of her daughter Bertha Jago. Roderick had access to neither.

What he did was damaging enough, editing Henry’s phrasing so it crucially omitted the fact Bertha had postnatal depression/mania. In the 19th century it was recognised that such illnesses were brief and the prognosis good, even without treatment. Bertha did regain her wits but Henry was never the same.

Their marriage had always been risky, the pair being young and indigent, with only a writer’s uncertain income to sustain them. For Lawson to take his little family to cold, lonely Britain, in search of a brilliant overseas career, was madness, but then it ran in his family.

He was also an alcoholic with a nasty temper, as publisher George Robertson warned Bertha. Naively she believed love could reform a drunk. Bertha was right, but not with Henry.

The book starts by pulling no punches, quoting Bertha’s petition for divorce on the grounds of drunkenness and violence from Lawson. National icon as wife-beater shock! It is perhaps no surprise: others suffered from Lawson’s stick.

Davies is firmly on Bertha’s side, arguing that the little woman was no villainess, rather truly heroic. She brought up two children alone, determinedly taking Lawson to court for his repeated failure to pay child support.

If he went to jail or asylum, better that than her children starve or be taken by welfare. As her letters make obvious, she walked a hard and lonely path. In the end she triumphantly succeeded while Henry cadged for loans that he drank away, along with his genius.

We now have supporting mothers benefits, grants for writers and treatment for the things from which poor Lawson suffered: deafness, depression and addiction. Bertha had little help, yet through hard work and willpower reared her children to be healthy, independent adults.

Davies is rightly in awe of Bertha for this feat. She found the same thing very difficult herself, even a century later. This book began as Davies’s memoir of being a single mother. It later morphed into a comparison, part personal, part scholarship, between her and Bertha.

The approach could be excruciatingly fangirl and has other dangers. Comparing your situation to the spouse of a famous writer can imply hubris. Davies’s husband may be irresponsible but he is no Lawson and she did not divorce him for cruelty.

A Wife’s Heart thus involves the biographer in the story, an approach most successful in AJA Symonds’s 1934 classic The Quest for Corvo, where the subject is so elusive it creates a mystery narrative.

In comparison Lawson and Bertha are well-documented. A book could be written about the marriage alone, without the biographer’s own life. The result is a hybrid text, and at some point somebody must have suggested it be memoir or Lawson story but not both. Nevertheless, Davies persisted.

At times the identification is too obvious, as when Davies discusses her own experience of being an artist’s model, with reference to Hannah Thornburn. The latter became Lawson’s muse and ideal, being forever young and conveniently dead. Lawson may not have known Hannah died from an abortion. But was she more than just the woman who got away? There are hints as to a third in the marriage, such as the woman “who wrecked our lives”, as Henry wrote to Bertha.

Davies discounts the role of Lizzie Humphries, the servant with whom Lawson decamped to London while Bertha was in the asylum. Nonetheless, he wrote most nastily about her, and further research on the Lawsons in England may reveal more to her story.

What emerges in this book is Bertha as indomitable. She even had her own happy ending, forming a loving relationship with bush poet Will Lawson (no relation), who gave up drinking for her.

Bryan has already written a memoir/biography about Henry Lawson, To Hell and High Water (2012). He and his brother Barrie retraced Lawson’s footsteps with Gordon. The two poets walked 200km-plus from Bourke in NSW to Hungerford in Queensland, an epic journey, significant to both men. Here they could play the swagman, as important an Australian figure as Lawson himself.

As the title indicates, Mates is about a friendship, although Bryan has the difficulty that the two men did not see each other for more than 20 years. When they did coincide again, the mates resumed where they had left off. Lawson was dead, though, within six years. In truth the pair spent little of their lives together.

Gordon emerges from Bryan’s account as a decent chap, authentically a bushman and worker. He was apparently among the few not to quarrel with the difficult Lawson. Gordon also had the luck to marry Celia McIntyre, daughter of a grazier, a woman with some money, who tolerated his restlessness. No Drover’s Wife nor Chosen Vessel she, for when bothered by a tramp she shot him.

Unlike Lawson, Gordon happily supported his family, and was a devoted husband. Certainly he drank, as was the national pastime, but not to Lawson’s excess. After Lawson’s death, he wrote about their friendship for The Bulletin, which also enhanced his reputation as a writer.

Again like Lawson, he gained a Commonwealth literary pension late in life: Ben Chifley was a fan. Yet his work appeared in book form late, in the 1940s, and is not, like his friend’s, still in print.

Indeed Gordon lacks an entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography. He is, as Bryan admits, forgotten except for his association with Lawson, where he is among many of the poet’s mates. Much of this lengthy book is necessarily about Lawson.

Gordon did not know Lawson during his married years, though he happily contributed to memorial volumes compiled by Bertha and her daughter. The mate’s code, as Bryan notes, precluded criticism. So does the psychology of the alcoholic. Gordon seems too sensible and kind a man to do more than listen, and not take sides.

He had little to say about the Lawson marriage. Bryan is therefore obliged to draw on Gilmore who, as a former Lawson sweetheart, was hardly disinterested. She was only second to Lawson in blackening Bertha’s name, mostly via a manuscript memoir. Bertha was recovering from severe mental illness when they first met, but Gilmore gives her nary any sympathy.

Reading Bryan beside Davies shows there are two sides to every marital story, as there are to friendships. Bryan performs a genuine service in retrieving a gifted bush poet who did not go off the rails.

Though anointed Lawson’s successor, Gordon slipped from the national consciousness. He lived to see some acclaim with the second of his books but never recovered from the loss of a son in World War II.

Of these two books, Davies’s is the more groundbreaking, in its defence of Bertha admirably setting the record straight. Bryan is more conventional. Both are the product of careful research, and function to some degree as complementary. Davies will be read by women, and Bryan more by men. Yet neither will be the last word on the Lawsons.

Kerrie Davis will be a guest of the Sydney Writers Festival, May 22 to 28.

Lucy Sussex’s most recent book is Blockbuster! Fergus Hume and The Mystery of a Hansom Cab.

A Wife’s Heart: The Untold Story of Bertha and Henry Lawson

By Kerrie Davies

UQP, 243pp, $29.95

Mates: The Friendship that Sustained Henry Lawson

By Gregory Bryan

New Holland, 488pp, $40 (HB)