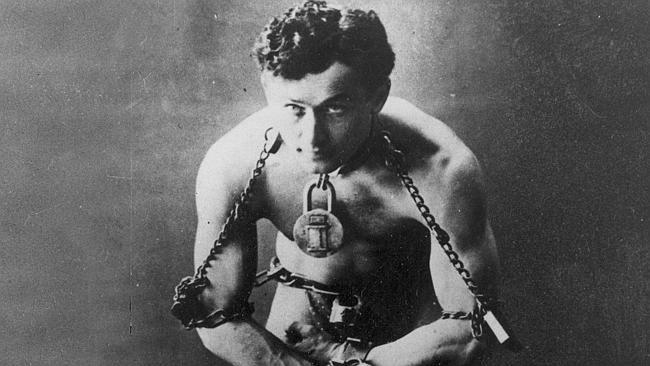

Unbelievable sleight of hand

THERE is something quintessentially American about the life of Harry Houdini.

THERE is something quintessentially American about the life of Harry Houdini. Not just because of his brilliant career as an escapist and illusionist, adventurer and aviator, professions in which genuine bravery and hucksterism exist in equal measure, or even because his life ended violently, but because the trajectory of his life and its acts of self-invention offer a perfect metaphor for the American immigrant experience.

Born the son of a rabbi in 1874 in Budapest, the man who became Houdini changed his name three times, from Erik Weisz to Ehrich Weiss to Harry Weiss to Harry Houdini, each time shedding some part of his past. It’s this that lies at the heart of EL Doctorow’s 1975 masterpiece Ragtime but it’s also central to Michael Chabon’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 2000 novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, a book that not only explores many of the same questions in the context of the comic book, but makes explicit the degree to which Houdini’s life served as an inspiration for that other great American creation, the superhero.

Steven Galloway is Canadian rather than American, and perhaps not coincidentally the version of Houdini conjured in his new novel, The Confabulist, is less interested in Houdini’s experience as an immigrant than his capacity to serve as a metaphor for the slipperiness of identity and the shifting nature of memory and reality. Appropriately, given the subject matter, the novel itself is a sort of sleight of hand, opening not in the past or with Houdini but in the present day with the narrator, Martin Strauss, an elderly man afflicted with a degenerative neurological condition in which the brain compensates for the loss of memories by inventing new ones.

Strauss greets the news he will forget his life and gain a new one with ambivalence, for his life has been lived trying to atone for his mistakes. The first of these is well-known: he is after all the man who killed Houdini. But the other is less well-known. For he isn’t just the man who killed Houdini, but the man who killed Houdini twice.

Ostensibly at least, the novel is the story of how this came to be, Strauss’s narrative of his intellectual deterioration framing alternating accounts of his life and that of Houdini, tracing the great man’s rise from his hand to mouth beginnings as a circus performer to international celebrity and on to his fatal encounter with Strauss and beyond.

It’s a neat trick, not least because it allows Galloway to play with the mysteries Houdini’s life offers, most notably by making concrete the suggestions he was for many years a spy, reporting not just to the US Secret Service, but to William Melville, the former head of Scotland Yard who went on to head MI5 (and who may have lent the initial of his surname to Ian Fleming’s M). And while Galloway’s rendering of his fictional world often feels surprisingly cursory it’s a lot of fun, at least at first, even if it becomes rapidly less plausible (and considerably less interesting) once Houdini and Strauss become entangled in the machinations of the espionage services and secret societies of spiritualists.

Yet the attentive reader will no doubt be asking questions even before Houdini’s fateful encounter with Strauss. After all, wasn’t the man whose punch purportedly ruptured Houdini’s appendix actually named Whitehead? And wasn’t the fateful punch supposed to have taken place in a dressing room rather than a theatre lobby? Likewise the chronology of Strauss’s account seems problematic: if he was a young man when Houdini died in 1926 how plausible is it that he is still alive in 2014? Even the name of his doctor, the “strange little Russian” Korsakoff, is suspect, given it is also the name of the syndrome Strauss seems to suffer from.

The novel’s point — one it states rather too baldly more than once — is that there is often little difference between reality and illusion. Like Houdini, Strauss is little more than a confabulation, “a shell to show the world”, his real self long since lost into the one he has invented for himself. Galloway wants to pull off a sort of magic trick with this idea, to show us how to live by reminding us that the way we remember the past is at least as important as what actually happened. Yet it never quite resonates, and not just because the novel shears away so many of the qualities that make Houdini such a fascinating figure, but because it forgets the lesson Houdini learns right at the beginning, which is that “you can’t amaze anybody if you don’t first make them believe”.

James Bradley’s new novel, Clade, will be published next year.

The Confabulist

By Steven Galloway

Text Publishing, 320pp, $29.99