Trent Dalton: How I survived an invisible villain

2020 is almost over but in a year of cold, hard numbers, there is one valuable takeaway.

The room is on fire. I know that’s a sombre title for what is about to follow but it sums up my feelings for this moment in time, for the sporadic ups and relentless downs of 2020.

I do like to give certain moments of my life serious literary titles. I feel it adds a sense of gravitas to such memories and helps me see them with a storybook clarity.

Clown on a String, Weeping is the title I attach to the time I went bungy jumping in New Zealand. Tender Plums is the week I spent recovering from my vasectomy.

Sometimes I borrow from masterpieces. Atonement is the explosive night I ate the last of my wife’s dark orange Lindt balls. Animal Farm is the month I spent covering the Queensland state election, aka The Divine Comedy, aka The Trial, aka A Season in Hell. And His Dark Materials is the time my marriage almost ended because I forgot to separate the whites from the darks in the laundry.

But back to Rooms on Fire. Margaret Atwood burns on a hallway bookshelf in my home in Brisbane. Geraldine Brooks burns in my lounge room. The Smiths, all the way from Manchester, are afire in my toolshed. These are among the lights in my life that never go out.

I have a theory about humans: all we’re searching for in life is another fire to sit around and tell our stories. Jack and Jill went up the hill to fetch a pail of water. We’re the only creatures who can tell you what happens next.

Some 300,000 years ago our heavy-jawed ancestors found ways to put fire to good use. They cooked with it, chased off predators with it, fought among themselves with it. And this, modern science tells us, made us human. Yet it wasn’t long afterwards that we realised the best thing a human can do with fire.

Let it burn. Leave it be. Look into it. Let it illuminate. Let it inspire. Let it fire up our beating hearts so we can fuel our souls and fill our heads with thoughts and feelings so true and important and inspiring that we have to share them.

We are evolutionarily and biologically compelled, body and soul, to turn to the person next to us and share something. This the sublime gift we gave to ourselves. Story. This is what made us human.

■ ■ ■

Two. Zero. Two. Zero. A cold set of numbers. Four of the darkest digits humankind may ever assemble. Twenty, twenty. A cold year.

I was driving home from school pick-up the other day and I asked my 11-year-old daughter how I could possibly put this year into words, this long year of cold numbers and brutal statistics.

“Write this,” she offered. “Some died young, some died old …”

She paused briefly and then waved her right hand with an Laurence Olivier-like flourish.

“And some had their stories told.”

The kid’s a fire and she keeps me warm.

■ ■ ■

Two. Zero. Two. Zero.

This long year of cold numbers. This long year of measurements. This long year of distances. The radius of a virus. The sweep of fear. The spaces between oceans, between cities, between mum and dad and sister and brother and daughter and son. Between Nan and Pop and the grandkids. The precious spaces between us. So faraway from each other but somehow so close. Maybe closer than ever before.

That nasty leveller pandemic that howled at our best-laid plans. That unforgiving virus that rendered every last disagreement, every last marriage squabble we ever had, ridiculous and embarrassing and privileged. That boundless traveller that stole our calm, our jobs, our financial security, our joy. That relentless killer that was skulking through the beautiful cities of our beautiful world, slipping into our own public spaces if we let it.

■ ■ ■

Strip it all back. Strip back the smart phones and the dumb clothes. Strip back the Twitters and the Instas and the TikToks. Strip back the endless tick-tocks of wall clocks sending you to work, to the grocery store, to school pick-up, to dance class, to soccer practice, to the comfort of bed. Strip it back.

Hell, this pandemic stripped it all back on our behalf. It stripped back the trees so we could finally see the forests of our lives. And here was the great answer resting in a perfect grass circle in the centre of that forest: All that matters are the ones we love.

What if all we really want is someone to love. What if all we really want is someone to tell our story to. What if all we really need from this wild and inexplicable life so lacking in answers … is someone to say goodnight to? Goodnight, my love.

■ ■ ■

It was a stonefish named Keef who saw me through 2020.

Keef is my late dad’s pet stonefish, also long-dead. My old man pulled Keef out of a crab pot in the Pumicestone Passage, Bribie Island, one hour north of Brisbane. He named him Keef after Keith Richards from the Rolling Stones and kept him in a glass jar of preservation fluid.

My old man lived alone battling emphysema for many years and was a master self-isolator, but the loneliness often caused him to go, as he put it, “a little bit loopy”. He’d find himself talking to Keef. “How ’bout them Broncos, Keef? What’s for dinner, Keef?”

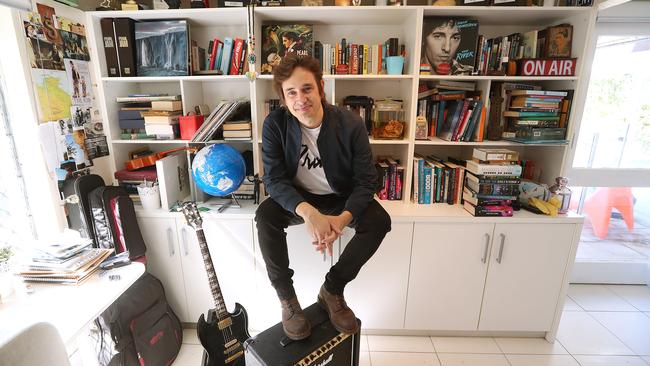

Now Keef watches over me from a bookshelf in my downstairs bunker as I write books and magazine articles. I wrote my first novel, Boy Swallows Universe, down there with Keef across 2017, each weeknight after work from 8pm to 10pm. Keef was a good ear for me through lockdown. I’d work through stories with him. “Does that intro work for ya, Keefy? Does that sound too Hemingway-try-hard, Keefy? Keefy, how do you spell the word, “Misspell?”

I remember in April I was putting the black bin out one day and I saw my neighbour talking to her cat. Peak lockdown. She looked like she’d become convinced her cat could understand her. It was the most extraordinary thing I’d ever seen. I went back down into the writing bunker and told Keef about what I’d seen and he nodded and said this pandemic was taking its toll on everybody.

■ ■ ■

My peak COVID-19 anxiety hit me in early April, about 3am. I woke up thinking about an Indonesian man I saw on the TV news. He was flat on his back on a main road at night, coughing hard and failing to suck air into his lungs. People were standing away from him, hundreds of people, and he was lying there, alone.

My mind jumped from that man to my Mum, who’s in her mid-60s and lives alone across town. Then it jumped to my brother and his family living across the check points of the Queensland-NSW border.

I thought about the things I touched through the day – self-serve supermarket touch pads, shopping trolley handles, the door to the post office – and then I thought about the nice bloke who recently replaced a faulty handle on our front door. He said he was overworked. “Home invasions spike in times of crisis.’’

I realised it was going to be a long year for us overthinkers. So to combat this useless overthinking I got out of bed and went downstairs to Keef and started writing down all the good things I’d been seeing across my neighbourhood. My notes on the apocalypse written through rose-coloured glasses. I wasn’t noting all the cold numbers and statistics. I was noting all the warm words on notes placed in letterboxes.

“Hello, my name is Ben. With the likelihood of increasing social distancing and quarantine at home … I thought it’d be good to get ahead of it and put myself out there for when people need help. I live at the end of the street and usually work as a musician, but with no gigs for possibly a long time I have time on my hands! I can serenade you from outside your door if nothing else.”

“Hi, this is Bob and Barb from Number 12. Just letting you know we’re here if you need us. Just letting you know we understand that none of this makes sense. None of it was in your life plan. None of it was supposed to happen. We don’t know where it’s all going to end, either, but we do know how we’ll get there. By smiling. By being kind. By getting out of bed.”

I noted the kids in our childcare centre fixing care packs for the elderly. I noted the people across Australia sitting in their living rooms sewing scrub caps and masks for hospital staff and the public. I noted all the humour. All the memes and text message gags that made all the difference, that made us feel so together. Together alone. I noted the “hang in there” looks we shared with strangers. So much understanding and conversation transferred in a single look.

Isn’t this just the most incomprehensible nightmare? It hasn’t just landed at your doorstep. It’s landed in your lap. It’s as close to you as your fingertips. I hear you. I feel you. Hang in there, stranger.

■ ■ ■

I turned all my late-night anxiety notes into a series of articles for The Weekend Australian Magazine called Tales From the Bunker. I asked readers to share their own bunker tales from isolation with me.

I received 725 pieces of correspondence from people across the country. Not just letters. These were stories. This was prose and this was poetry. This was bloodletting and release and this was longing.

And this was fire.

Most of the letters didn’t directly mention coronavirus. If there was an underlying thematic current to them it was the need for all of us to return to our individual fires. All the things that lit us up and kept us warm.

Family. Friends. Love.

That invisible villain temporarily stole our stories in 2020. It temporarily muted us. Made it so hard to turn to the person next to you, turn to the ones we loved, and tell a story.

But we found a way. We made do. We logged in to that maddening thing called Zoom and we tapped on that flash box marked “unmute”. We hit the unmute button. And this was the great human unmuting. We told our stories again. We found our fires again. Long may they keep us warm.

Trent Dalton is a journalist at The Weekend Australian and author of the novels Boy Swallows Universe and All Our Shimmering Skies. This article is based on his Brisbane Writers Festival End of Year Address at the Institute of Modern Art on December 3.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout