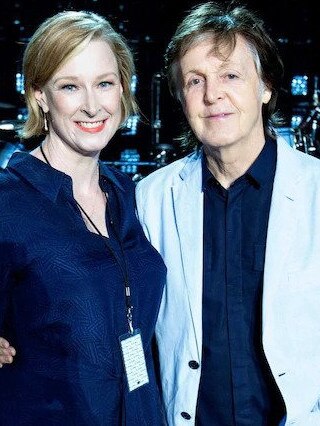

Trent Dalton and Leigh Sales on politics, the Logies, the ABC and why she’s grateful for Annabel Crabb

Leigh Sales interviewed Trent Dalton for her new book about storytellers. What happens when we turn the tables, and ask him to interview her about politics, the Logies ... and Leigh’s terrible undies?

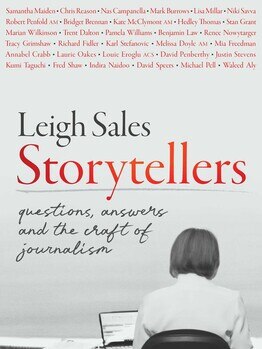

Bald Hills is the northernmost suburb in Brisbane. It’s about as fringe as fringe gets for the river city. It’s known for its featureless cattle-grazing hills and a thing called the Bald Hills Radiator, a 198m AM radio transmitter tower that local kids on BMXs lie to their friends about climbing after dark. It’s also the childhood home of a flame-haired, fire-bellied journalist named Leigh Sales who climbed to the highest rung of Australian media, winning three Walkley awards in the process. In her latest book, Storytellers, Sales reflects on her 30-year rise from newsroom grunt to powerhouse anchor and interviews the cream of Australian journalism about how and why they tell the stories that shape our lives. Journalist and author Trent Dalton features in the book, and he caught up with Sales on the eve of the book’s release.

Dalton: You grew up one suburb away from me in Bald Hills on the northern fringes of Brisbane. How aware was a young Leigh Sales of the world around her in those years and from where was she accessing her news?

Sales: Our family had one TV in the lounge room. It was on Channel 9 news. We’d hear the thud of The Courier-Mail landing on the front driveway. I wasn’t paying close attention to the news by any stretch, but I tell you what I was back then: a massive stickybeak. One of my favourite things to read were the advice columns in my mother’s Woman’s Day and New Idea because I just found ordinary people very interesting. Reading about other people’s problems was a way of being plugged into another world out there.

I think I unconsciously built an invisible wall around that area when I was growing up. I think that wall kept me and many of my friends from reaching places we thought we weren’t allowed to go. Does that make any sense to you at all?

The key to it is the love of my parents, people who gave me the sense that I could do anything I wanted to do if I worked hard. It’s only as an adult that I realised opportunity is certainly not equal. It’s a total credit to my parents that they worked so hard to give me and my brother opportunities. It’s also a credit to the people in our neighbourhood: the kids I was friends with; people who were honest, hardworking people. In my journalism I never lost sight of those people.

Storytellers is a rattling, often revelatory, tribute to journalism and Australian journalists. Why this book and why now?

I feel we’re all storytellers. Whether it’s talking to a neighbour over a fence, making a presentation at work, a lawyer persuading a jury, a pilot making an announcement, all of us, every single day, are connecting with other human beings by telling stories. There are things you learn that make you better at telling a story. I feel like some of what we know as journalists would be useful for anyone to know. But then also newsrooms have changed a lot over the years since I was a reporter. When I first started in the 1990s, everyone was on a desk phone, you could hear the way people would interview, talk to contacts. You would pick up a lot just by being in a newsroom. You also had more opportunity to work with senior reporters who would teach you the tricks of the trade. I felt like it was important to collect the combined wisdom of all these journalists. I would have loved this book when I was starting out.

Each journalist was extremely candid in the book. There’s always a brutal honesty when journos converse, as if we’re all unconsciously paying tribute to that thing we’re all preoccupied with finding, the truth.

Many people in the book I’ve known for a long time, that really helped the candour. What really struck me was how much each journalist communicated like the journalism they do. Chris Reason and Mark Burrows have a way of speaking that is short, sharp and punchy; that’s because they’re television reporters who have 90 seconds to tell their stories. Then you speak to Pamela Williams, one of the great investigative journalists, she takes you through an anecdote in forensic detail. And then you, Trent, as a feature writer, your interview is full of mini feature stories that you’re telling about your life. The question is, does the work shape our personalities or does the personality shape the work?

What was the finest piece of journalism you ever consumed?

I distinctly remember reading Joe Cinque’s Consolation by Helen Garner and thinking, “Wow, you can do journalism like this?” You can apply the techniques of a novel to nonfiction. That was revelatory. I really aspire now to write with her sparseness, even the questions I write for interviews. I wrote the foreword to the 25th anniversary edition of Helen’s book, The First Stone. I sent Helen the foreword to have a look at and Helen replied asking if I would mind if she had a stab at editing an anecdote I had opened with. I was like: “Oh my god, yes.” Helen sent it back and I was able to compare her version to mine. She had cut a third of the words and I can’t even tell you the pleasure of seeing what she had done to my words. The craft she employed to make that anecdote so taut. It was almost orgasmic.

What was the worst act of journalism you have witnessed first-hand across 30 years?

It’s actually my own mistakes, to be honest. Often, failures of empathy. I was sent to cover Hurricane Katrina in 2005. I was at the New Orleans airport, which had turned into a makeshift crisis centre, and I was under massive deadline pressure to find people to interview and I found this grandmother with five or so kids. She was quite upset because she had lost family members and she couldn’t find people. She was trying not to cry but I kept asking her questions because I knew I would have enough to file if I just asked her a couple more questions. Then this little boy with her, about 11, said to me, “That’s enough.” He could see his grandmother was getting more upset. And I heard him but I pretended I hadn’t heard him because I knew I didn’t have enough. So I asked another question and the boy said in a louder voice, “That’s enough.” I stopped asking questions but I thought: “Wow, it took an 11-year-old to tell me enough was enough.” But you’re thinking about the stuff that’s not in front of you. You’re thinking about the fact you’re gonna get your arse kicked if you don’t meet this deadline.

I loved what political journalist Samantha Maiden says in the book about how so many of her scoops come from having “the shits”. Anger is a powerful tool for a journalist.

In television you’ve got to try not to show your anger. One of the reasons I needed a break from doing a show like 7.30 is because almost every night of the week you would have stories where ordinary Australians have been let down by people in positions of power. Banks, insurance companies, priests, teachers, scout leaders, even the Australian cricket team. That would make me mad. Why does the average person get taken for a mug so often? But that anger would steel me sometimes to ask difficult questions.

What do you miss most about 7.30?

I’m not missing it. It was the right time to go. It took a lot to do that job for a long time. I had to muster up my courage all the time. It would upset me to see sadness and tragedy and terrible things happening to people. I just needed a break from it. I kinda just walked out and I don’t miss that life: talking to someone like you now and realising that this conversation has caused me to miss eight important calls on my phone. It was fun for a long time, but I just needed a rest.

There’s a very worrying trend lately of journos having to seek police intervention in matters concerning stalkers and trolls. What’s the worst you experienced at the peak of your 7.30 tenure?

I’ve had police intervene multiple times. The volume of threats against me was so high that the ABC would be monitoring it because I didn’t want to have to see it myself. It’s horrible because you do worry for your personal safety. Towards the end of my time at 7.30 that had become tiresome. Too much. And nobody watching 7.30 at home that evening goes, “Well, that was a pretty good interview with the Prime Minister considering she has two sick kids at home and she got threatened with being raped and murdered this morning.”

When have you been the most grateful to have your Chat 10 Looks 3 podcast co-pilot, Annabel Crabb, in your life?

On the day my dad died. I got the phone call to say he’d had a heart attack and was on life support. I had to go up to Brisbane. I rang her and said, “Shit.” She came straight around and drove me to the airport. I forgot I’d left washing on the line and I asked her if she could take it in and she texted me the next day saying, “Mate, listen, we need to get you some new undies because I’m sure these looked pretty good in Pound Savers when you bought them in 1983, but they’re a bit worse for wear now.” I’m sitting at my mum’s house at the dining table with the funeral organiser and Crabb’s sending me hilarious little one-liners like that. It was the perfect mix of care and normality. Then I came home and she got me from the airport and in the car on the way home I was thinking about how I had no food for dinner for the kids. Then we got to my house and she opened her boot and it was full of groceries. That’s Crabb.

What’s the one Logies story you only tell your friends after midnight?

The issue for women at the Logies, especially when they are not on in your home city, is getting out of your dress. They can be very hard to get in and out of. When I got home from the Logies on the Gold Coast last year, I got back to the front desk of the hotel. There was this poor guy, about 21, on the front desk and I said, “Mate, I need to ask you a question and it’s gonna sound pretty sleazy: Could you please unzip my dress?” I was thinking, “I hope I’m not going to wake up to the front page of the Gold Coast Bulletin to a headline reading, ‘ABC fat cat sexually harasses front-desk clerk!’ ” Occupational hazard of the Logies, you get home after midnight and you turn back into a pumpkin.

What do you say to friends now when they tell you their child wants to become a journalist?

I tend to say there are things about journalism that are hard: the pay’s not always great; it’s shift work; the hours are terrible on relationships. But if I dropped dead this afternoon, one of the things I’d feel so grateful for is the job I’ve had. It’s not the easiest path to take necessarily, but I’ve really loved that path.

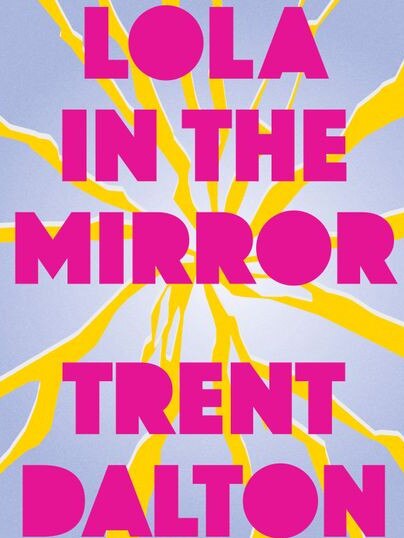

Storytellers: Questions, Answers and the Craft of Journalism by Leigh Sales (Simon & Schuster, $36.99) is out now. Trent Dalton’s new novel, Lola in the Mirror (HarperCollins, $32.99), will be published in October.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout