Tracker Tilmouth: A raucous choir of one man’s selves

Leigh Bruce ‘Tracker’ Tilmouth was one of those figures so larger-than-life that only the Top End could contain him.

Leigh Bruce “Tracker” Tilmouth was one of those figures so larger-than-life that only the vast spaces of the Top End could contain him. His early story was drearily, tragically, common for its era. It should have done him in — left him broken in spirit or else killed him, just as it killed many of his generation — but he exceeded his circumstances and used them as rocket fuel, powering a can-do activism that was equal parts bush politics and serial entrepreneurship.

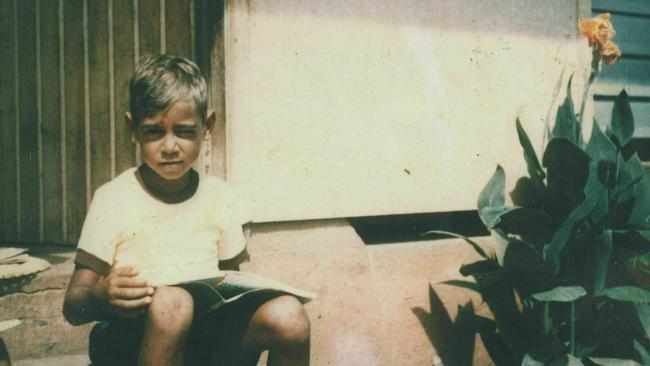

He was born an Eastern Arrente man in 1954 and spent his early years in Alice Springs. When his mother died he was still a young boy, and while an aunt and uncle sought to adopt him, welfare authorities decided that he and his two younger brothers — the “dark ones” out of eight siblings — should be sent north: first to Darwin and a notorious children’s home, then to the mission on Croker Island.

In this, he was luckier than many others in the Stolen Generations. He had some family with him in an idyllic, wild, if very rustic home, and a fair-minded, devout house mother who tried to awaken in the children some sense of their circumstances by reading them novels such as Alan Paton’s apartheid-era Cry, the Beloved Country.

Sent back to Darwin for his education, Bruce Tilmouth showed himself to be precociously clever and defiantly ill-adjusted for school. He dropped out young, worked in an abattoir and became involved in petty crime before being sent to Angas Downs station, an indigenous-owned property where he was taken in by people connected with his birth family. There he divided his days between residual traditional culture and the dusty business of running and maintaining a working station.

He remained a joker and an annoyance to more stolid co-workers on the station, but a seriousness of purpose crept in. The arrival of the Whitlam government and the good offices of Charlie Perkins opened Tracker’s horizons. He studied environmental science and natural resource management at Roseworthy College and, in his own words, “got some letters after my name”.

The latter part of Tracker’s life and career is part of the public record. Among numerous roles he was director of the Central Land Council, which represented Aboriginal people across an area more than 10 times the size of Tasmania. He helped establish the Central Australian Aboriginal Legal Aid Service, as well as the region’s Aboriginal health service, and he was frontrunner for preselection for the ALP’s Senate seat in the Northern Territory before dropping out of contention.

Prior to his early death from cancer and heart problems at 62, Tracker placed his considerable energies, political nous and generosity of spirit in the service of advancement for indigenous Australians. He had no time for passive welfare programs and believed that a vibrant indigenous economy was the basis for cultural rejuvenation and political power. This position, combined with a take-no-prisoners approach to negotiations with white politicians and other indigenous movers and shakers, made him a figure of ambivalence: he infuriated as many as he charmed.

Such is the front-office account of Tracker Tilmouth’s life and achievement. And yet, great complexity lays the transmission of Australian indigenous experience via Western literary genres contained under the umbrella term “life writing”. The idea of a single life, celebrated or examined in a manner bracketed off from other selves — that rich, relational matrix of family, community and wider society so important to First Nations’ culture — is a European invention dating mainly from the romantic era. It is a genre undergirded by the political auto-inventions of Napoleon, the solitary metaphysics of Rousseau, the literary performances of Wordsworth, Chateaubriand, de Quincy and others, all concerned with prismatic shifts in individual consciousness over time.

Romanticism is also characterised by a notion alien to what non-indigenous Australians — imperfectly, even today — understand of Aboriginal philosophy and worldview: that of humans divorced from, even actively fighting against, nature.

As the historian of ideas Isaiah Berlin, writing about the German playwright Schiller, put it: “he makes a vast contrast between nature, which [is] elemental, capricious … and man, who has morality, who distinguishes between desire and will, duty and interest, the right and the wrong, and acts accordingly, if need be against nature”.

So, autobiography in its Western forms may be problematic for individuals such as Tracker.

Yet he regarded life-writing as a necessity (“I want you to write something for me, Wrighty,” he tells Alexis Wright). To be treated as citizens of a democracy, for example, one must first be regarded as a person deserving of those rights and duties; however unfair the obligation, telling the story of the self becomes a precondition for political agency in the indigenous context, even if it is automatic for others. Recovering what was lost over two centuries of displacement, exterminatory urges and assimilationist policy also makes it an existential obligation to assemble and verify the narratives that remain. For collective experience is no more than a mosaic of fragments made up of individual lives.

Similarly, engendering that sense of pride and community which is the basis for survival in any embattled culture requires heroes and heroines, stories of conflict and reconciliation; models of probity, decency, outrage or wisdom to admire and emulate. Most importantly for those of us who are latecomers to this continent, writing self in the indigenous context offers an opportunity to meet, recognise and hopefully empathise with a life perhaps very different to our own.

Author and activist Alexis Wright has impaled herself on the horns of this dilemma in Tracker. Hers is not the introduction to an autobiography, though Tracker’s words and recollections make up a good chunk of the total in these pages. Nor is it a biography, strictly speaking, since there is no organising intelligence filtering the multiple voices, imposing a singular vision of his life through selection, interpretation, expansion or elision of people, places and events.

What she has produced instead is a “collective memoir”: a curated account of Tracker’s life and work told through the voices of those who knew him. It is a democratic undertaking with a strong tang of oral tradition, even on the page. Its dominant mode is the yarn — the tale whose point is in the telling — and the tone is laconic throughout. There is a lack of sentimentality here, even in the description of terrible events or circumstances; more often there is the anarchic energy of those who have nothing to lose.

The total effect is one of narrative imbrication: stories overlapping one another like scales over snakeskin. One person’s perspective of an event is bolstered, enlarged, undercut or illuminated by another. The effect can be slyly comic or it can burrow further down into a private grief. The multiplicity of perspectives can be exhausting — think of it as “slow biography” — but it is also a form that manages to encompass the communal experience of indigenous Australia while celebrating a visionary individual.

What Wright has achieved in Tracker is a considerable literary workaround. She has found a method that enacts the complex relationship between self and community that a Western biography could not — and one also shaped to Bruce Tilmouth’s position, caught as he was between traditional culture and the pressures placed upon that culture by the demands of the present. There is a cumulative power in the repetitions, backtrackings and digressions the formula necessitates: a sinuous, elegant accommodation to a raucous choir of selves.

It is a book as epical in form and ambition as the life it describes.

Geordie Williamson is chief literary critic of The Australian.

Tracker

By Alexis Wright

Giramondo, 650pp, $39.95

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout