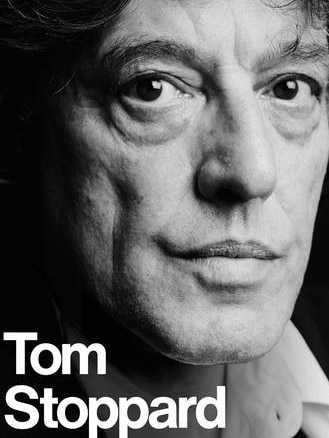

Tom Stoppard exposed: revealing biography of a literary giant

When the playwright extraordinaire was asked by Virginia Woolf’s biographer why he wanted her to write his life, he replied, ‘‘So people will read it.’’ And so they will.

When Tom Stoppard, playwright extraordinaire, was asked by Hermione Lee, famed biographer of Virginia Woolf and former professor of English at Oxford, why he wanted her to write his life, he replied, ‘‘So people will read it.’’ And so they will. This story of the boy with the Czech Jewish background who felt neither and would become more English than the English is enthralling.

Stoppard made love to the glories of being an Englishman under a constitutional monarchy and he idealised British tradition and celebrated it through his complexly dialectical plays about everything under the sun.

His play about Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, the two parasitic bit players in Hamlet, became an instant classic. The Real Thing hit Broadway with Jeremy Irons and Glenn Close, directed by the great Mike Nichols, winning every Tony award in sight and led to the playwright writing the script of the film Empire of the Sun for Steven Spielberg.

Everyone from Harold Pinter to John le Carré adored Arcadia, the play where the teenage girl is discovering far-out mathematical theorems and the 20th-century literary people – played by Bill Nighy and Felicity Kendall in Trevor Nunn’s original production – are nutting together all sorts of fascinating facts about Lord Byron and his contemporaries.

Stoppard wrote the Sean Connery/Harrison Ford scenes in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade and he won an Oscar for Shakespeare in Love. Who but he could have had Vaclav Havel, Mick Jagger and Pink Floyd at the first night of his 2006 play Rock’n’Roll when it opened at London’s Royal Court?

Now 83, he is the greatest compound of the popular and the highbrow in drama since George Bernard Shaw and it’s typical of him not only to have said that only in America was Shavian a dirty word but to talk about something as ‘‘close Shavian’’.

The boy who in 1946 got to England via India, courtesy of the prescience of his doctor father, who died in the process, was good at school, the maths as well as the Greek, and seemed destined for Balliol or Trinity but he wasn’t interested.

Instead he landed a job on a local newspaper and hung out at the Bristol Old Vic where he became a close friend of Peter O’Toole and saw him doing Shaw and Shakespeare and John Osborne’s Look Back In Anger. As Lee says, this was his university. He had a great gig writing a facetious column and he kicked round with a great actor even if there was the downside of being in love with a girl who was in love with the actor.

Eventually he hit London and wrote features for an arts rag under one byline and reviews under another. When he went for a mainstream job Charles Wintour (editor of The Evening Standard and father of Anna) asked him if he was interested in politics.

He said yes. ‘‘Who’s the Foreign Secretary?’’ Wintour asked. According to legend Stoppard replied, ‘‘I said interested, not obsessed.’’

This kind of wit and charm follow him wherever he goes. He said once the good thing about success was that you didn’t have to worry about identity too much. He seems to have got on with everybody, partly because of his deliberate effort not to quarrel.

Stoppard always said things like, ‘‘I try to act as if there’s a God. I don’t know where this leaves the question of faith”. He used to pray for the women in his life and he would also say, of his supposed intelligence, ‘‘The iceberg is all tip.’’

He was clearly always someone of formidable self-possession, even as a young man. Very young and very impecunious he asked his agent to lend him some money and when the man gave him what was in his pocket he immediately hailed a cab while his benefactor caught the bus.

When he’d written Jumpers – the play with Michael Horden about logical positivism versus moral absolutes – for Kenneth Tynan in his days at the National, he had to read it before a Sanhedrin of theatre heavies including the head of the National Theatre, Laurence Olivier.

He wasn’t confident doing the voices so he had a series of name cards to hold up. He increasingly got them mixed up. While Tynan and Michael Blakemore looked on in polite pain Larry stared at the ceiling until Stoppard finished and then said, in the voice that roused Agincourt and had the princes murdered in the tower, ‘‘Ken, where did you get that light?’’

But there is a world of seriousness in this book as well.

When Stoppard wrote Night and Day, with Diana Rigg as a dazzling siren and John Thaw as an Australian journalist in a ghastly African country, he had a disagreement with fellow playwright David Hare, who was appalled at journalists writing things they knew to be untrue.

Stoppard wrote back to Hare, suggesting he might be trivially right but he was substantively wrong. He was for the Fourth Estate as an ultimate protector of liberty.

All of this went along with a horror of Marxism and a sympathy for Margaret Thatcher and her battles against the unions. Travesties, his 1974 play about James Joyce and the surrealist Tristan Tzara (played by John Hurt) uses the speeches of Vladimir Lenin verbatim – to indicate that he was just Joseph Stalin with a better face.

To his credit Stoppard was always passionately concerned about human rights in Russia. It was in 1977, however, that Tynan, his early backer and a champagne socialist of the classiest vintage, published a piece about him in The New Yorker that said his basic stance was ‘‘See how self-deprecating I can be and still be self-assertive”. Tynan argued that “Tom’s modesty is a form of egotism’’ and also probed the history of his Czech Jewishness.

When he became famous with The Real Thing he said, when asked, he was ‘‘Jew-ish’’ but he’d never felt either Czech or Jewish and this was buttressed by his mother who called herself Bobbie not Martha, and who minimised any foreignness.

It was Robert Silver of The New York Review of Books who had the brains to send Stoppard to Czechoslovakia, where he found a soulmate in Havel, and it was an aunty who opened his eyes to the relatives who died in Theresienstadt.

His mother died in 1995. When he accepted a knighthood he said to his brother, ‘‘If only Mum could have lived to see this!’’ He wrote to her every week of his life.

The other women in his life included two of his leading ladies, Felicity Kendall and Sinéad Cusack, married to Jeremy Irons. He married three times.

Samuel Beckett said of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead that it was good to be understood and not just copied. Stoppard played cricket with Harold Pinter who respected his Toryism and he was wicketkeeper for another old lefty Dame Peggy Ashcroft who gave her last lustrous performance in his 1991 radio play In The Native State.

Stoppard said once: ‘‘The strong argument is to behave decently before you do the arithmetic because the arithmetic is never going to be that bad. There’s a lot of space, money and goodwill in England.’’ David Hare said of this, ‘‘That’s why I love this man. It so perfectly expresses the way he thinks.’’

If you want to read a huge biography of a man who is both brilliant and good, get hold of this thousand page glory of a book.

Peter Craven is a cultural critic.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout