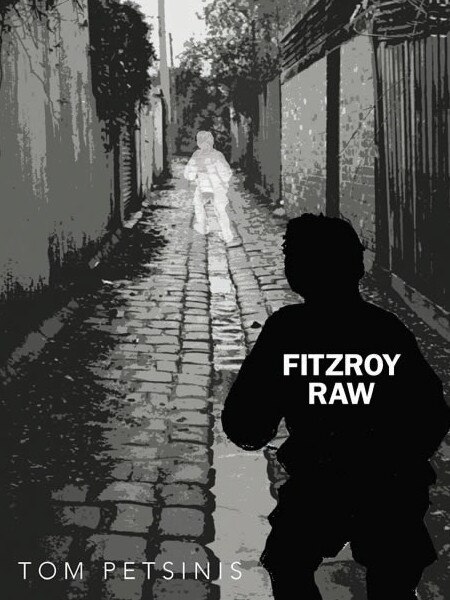

Tom Petsinis’s Fitzroy Raw recalls 1960s Melbourne

Fitzroy Raw is a semi-autobiographical novel about a boy from Macedonia that runs from the late 1950s to the moon landing in 1969.

“I was bilingual to the age of six, trilingual thereafter and quadrilingual by 15 when I discovered the wonders of the language of algebra,” Petsinis tells me. Fitzroy Raw is a semi-autobiographical novel that runs from the late 1950s to the moon landing in 1969. It’s about a boy from Macedonia who at age six moves to Australia with his mother, Menka, to join the “stranger” who is his father. Vangel, his dad, has been there for three years, working to earn the fare for his wife and son.

When the lad is enrolled in primary school, the principal asks his name. Vangel says it’s Kolche in Macedonian and Nikolaos in his Greek passport. The principal thinks this is too hard and decides, “Nick. We’ll call him Nick.” Petsinis, born the same year as Nick, also has three names: Tome (Macedonian), Thoma (Greek) and the one he has lived with for most of his life, Tom.

Set in the Melbourne suburb of the title, this is a beautiful novel full of truth, humour, drama and a little sadness. It returns me to my school days. I’m a decade younger than Nick and I was born in Sydney but I will never forget being in a high school that was broadly divided between “Aussies” and “wogs”.

I was in the Aussie camp, mainly because I was OK at rugby union, the main school sport (in Petsinis’s novel it’s Aussie rules and the Fitzroy Lions, which would later become Jack Irish’s team). But there were times when I was called ‘‘wog” due to my Italian surname and it hurt. I recall the “wog’’ population at school as being in three main groups: Greeks, Yugoslavs and Maltese. Not many Italians. Of course the ethnic mix was more diverse, more complicated than that, as Petsinis shows with gentle affinity.

The scene where hostilities break out in a Melbourne cinema during a screening of a film about Alexander the Great — is the world-conquering warrior Macedonian or Greek? — is wryly funny. What makes it even funnier, not mentioned by the warring Macedonian and Greek characters in the novel, is that the on-screen Alexander was a Welshman known as Richard Burton.

There are lots of moments in this novel that make me laugh, including the appearance of an Italian student, Santo Giavanucci, who has an “accent stronger than his breath after a mortadella sandwich”. I laugh because my mother, of Irish-German descent, would never put mortadella on a sandwich, or anywhere else.

It’s the six-year-old Nick who is the funniest, in a bittersweet sense, as he navigates an “unfriendly country” and a father he does not know. Seeing a photograph of the Queen in the principal’s office, he thinks of the portraits of Christ in his home village. “Is this woman the God of Australia?” he wonders. When he first meets indigenous people and is told they are the true Australians, he innocently asks, “If it’s their land, why are they begging?”

When he’s a little older, 10, he considers the differences in Macedonian and Greek language. Greeks, he knows, can’t pronounce “ch” and “sh”, so for them it’s “fis’n’tsips instead of fish’n’chips, even though they have a monopoly on this kind of shop”. So true! says my childhood self. Then there’s January 6, St John’s Day. It’s scorching hot but that doesn’t deter Nick’s father from “insisting they visit a dozen relatives named John”.

Even so, Nick understands the sacrifices his parents have made. They left their country, their family, their language and worked hard, so that he would not have to when he grew up.

Nick is good at maths, but two accidental moments lead him towards reading and writing. The simple one is when, at 13, he ducks into the local library with his slightly dodgy friend Vlad, who takes a leaf from the Macedonian-Greek playbook. He and his family are no “Yugoslavs”, he warns. “We’re Serbs and we’ll die Serbs.” Vlad is there to steal old books that he can resell, but each boy soon falls under the spell of the shelves.

Nick sees a woman browsing and senses “the power of words”, the “magic that brings a sweet smile” to her face and “raises her from poor Fitzroy to a place richer than Toorak, that turns her flesh and bones to the stuff of timeless thought”.

The less simple one is when a younger Nick, keeping score at his father’s card game, swallows the small pencil he is using. His mother wants to take him to the doctor but his father rules there is a cheaper solution: castor oil. Some uncomfortable hours later, the pencil does come out. His father muses that “anyone who likes pencils so much is destined to become a writer”. His mother washes the pencil and gives it to her son as a keepsake.

The mathematician author, who will soon publish a sequel, admits that while the based-on-life novel has “considerable elaborations”, this little pencil is 100 per cent autobiographical.

Today I want to mention an Australian novel published by a small publisher: Tom Petsinis’s Fitzroy Raw (Tantanoola, 298pp, $29.99). Melbourne-based Petsinis, perhaps better known as a poet, has a well-behaved website, which comes as no surprise. His day job is as a mathematics lecturer at Victoria University.