Tim Ross’s journey from comedy god to architecture guru

Tim Ross, once one of radio’s most successful presenters, shows us why good design matters and how the spaces we inhabit shape the memories of our lives in Designing a Legacy.

It’s hard to believe that the urbane Tim Ross, the design commentator with the almost evangelical belief in the indoor-outdoor spaces and raised structures of mid-century modernism, was once one of radio’s most successful presenters.

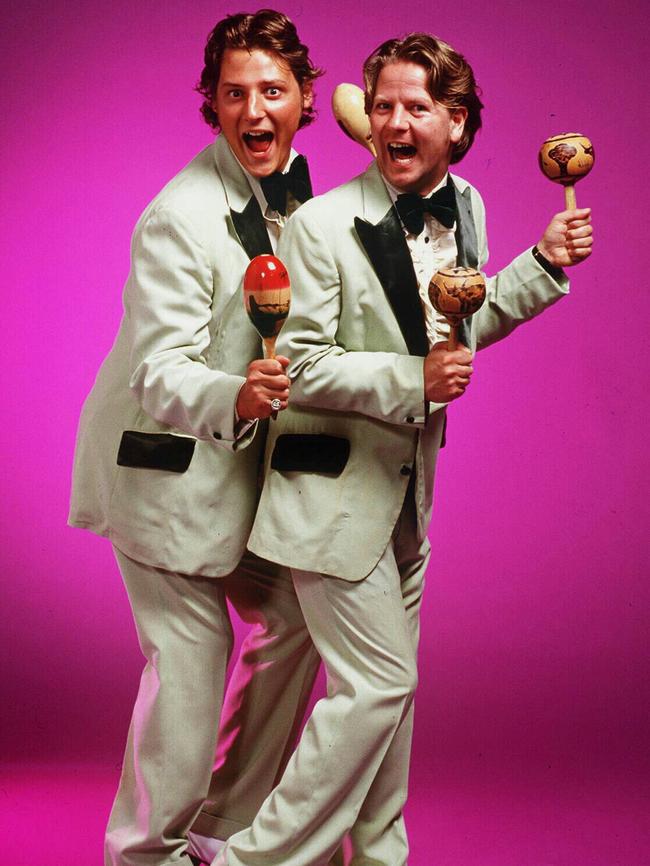

For years he worked with the disorderly and very funny Merrick Watts on Nova’s The Merrick and Rosso Breakfast Show, the two comic performers working furiously live in the force-field of a new kind of radio.

Rosso sat across from the hyperactive Merrick, his hands on the show’s many strings, though sometimes seemingly submerged by microphones, electrical leads, piles of papers and props. Looking slightly dishevelled in long, baggy board shorts and thongs, sagging rather than sitting, he managed to still dexterously manipulate the show’s many elements: the promos, announcements, interviews, talkbacks and comic set pieces.

Well now, beautifully turned out as always these days, his hair elegantly coiffed, a distinctive high wave prominent, and his wardrobe rather hipster in style, slim-cut and coolly elegant, Ross, the self-described “nutty modernist”, is back in Designing a Legacy Part 2.

It’s the sequel to his first show, which was a idiosyncratic and entertaining documentary look at the nature of design. It was a cleverly conceived part history program, part literary meditation and part TV architectural magazine. And while a long way from breakfast radio, a joke or a quip was never all that far away in Ross’s presentation.

And again, as in his first show, Ross offers a kind of aspirational property evangelism, as he espouses his fervent belief in architecture designed with conviction and consideration and the way it shapes the lives of the people who live in it. “I’m on the hunt for great Australian architecture,” he says at the start, during a droll montage where he traipses through various neighbourhoods of rather typical humdrum housing. “We’re in a country where we’re all obsessed with our houses, but we don’t celebrate our architects and design enough.”

In the first show, he featured iconic modernist masterpieces designed by legendary Australian architects including Robin Boyd, Esmond Dorney, Gabriel Poole, John Andrews, Chancellor and Patrick, and Ken Woolley. And presented us with a charming sense of the daring and provocative spirit of an era where architects were part of the national conversation, constantly taking part in arguments about the narrowness and sterility of Australian life.

As the late Robin Boyd, an architect of great interest to Ross, said, “Australia’s is a special kind of philistinism, an immovable materialism which pits art and ideas of any kind deliberately and firmly to one side and lets the serious business of living proceed without distraction.”

Well, in some ways not all that much has changed, but the amiable Ross wants to open our eyes a little to what great design can bring to our lives. He introduces himself at the start and says without apology, “I love buildings”.

He even lives in a classic modernist 1959 home, replete with kidney-shaped pool and red Lino floors. And instead of altering the house to accommodate their two children, Tim and his wife Michelle honoured architect Bill Baker’s original work that dates to 1959.

In his new show Ross shows us how housing structures can shape our lives, that “the story of what we build is the story of us and that story isn’t always what we expect”.

He looks at stunning architect-designed private homes, a school, a surf club, a historic motel, a museum and art gallery and a mosque. And his droll but informed commentary, and some lovely film, demonstrates that great architecture reveals respect – for the people that use it, for the environment around it and crucially in this country, for the ancient history of the land.

Ross is the writer and executive producer with Sally Aitken, whose work includes the multi award-winning documentary series, Streets of Your Town that she made in 2016 with Ross, and The Pacific in the wake of Captain Cook with Sam Neill and Getting Frank Gehry. The director is Chris Eley, a Bafta award-winner and nominee his films and series have been shown on the BBC, Channel 4, Sky Arts, Arte France and France Television.

And his direction is as hip and amusingly understated as his presenter, combing interviews, period news footage and TV advertisements, soaring drone sequences, and some elegant home movie footage from the archives of the architects Ross interviews.

The first episode looks at the notion of “place” – and the way we have finally started to outlive the colonial vision which largely ignored the Australian landscape in which buildings were situated. (As Boyd, said in the 1960s, “Australia is, in fact, an old man’s bureaucracy.”)

Ross takes us to Bruny Island, off the East coast of Tasmania to meet architect John Wardle, who shows us his stunningly redesigned colonial cottage known as Shearers Quarters, a beguiling companion building to an existing historic cottage on a working sheep farm.

A building of surprising angles and lines, it looks into the land on which it sits and embraces its dark past. It’s easy to imagine posses of shooters in the past organising to go out and hunt the indigenous inhabitants of the beaches and valleys surrounding the house. And Ross demonstrates with Wardle just how buildings are full of stories that resonate through the generations.

Then he’s off to Bundanon’s Art Museum and Bridge and its erudite and entertaining architect Kerstin Thompson, who was inspired largely by rural Australia’s trestle flood bridges. There’s also a new subterranean gallery buried inside a reinstated hill, its intrinsic drama coexisting with the works in the gallery on site.

Another surprising inspiration for Thompson was Robin Boyd’s 1961 Black Dolphin Motel, that “architectural tranquilliser by the Pacific Ocean”, designed by the architect without overly flashy finishes, neon lights or all the trappings of American ostentation. “The landscape of our holidays was so often the highway – so being able to pull right up at the door of where you were staying was somehow magical,” says Ross.

It’s a lovely sequence, with resonance to so many of us, especially to me. Like Ross, at an early age I fell in love with motels. They drifted into my adolescence about the same time as television and the tilted towering screens of the Drive-Ins, futuristically blank eyesores during Melbourne days, and car palaces at night.

There were some motels in Coburg, on the road to Sydney, that my family occasionally drove past, and they were a new kind of architecture, symbols of mobility and convenience, with neon signs, brick veneer and tarmac precincts of parking space where cars looked into the huge bay windows of the rooms.

I stayed in one on a school excursion to Tasmania. I can remember thinking that this must be like living in America: a television set in the bedroom, tiny packets of wrapped soap and a breakfast that was shuffled through a hatch in the door. Then they started doing motel jokes on In Melbourne Tonight and Sunnyside Up.

“They reckon after he left Canberra after the conference all the motels flew their bed sheets at half-mast,” Syd Heylen and his comedian mates would joke. “I always feel sorry for anyone with a name like Smith. It’s so embarrassing registering in motels.”

Robin Boyd loathed them. And as Ross shows, Boyd revolutionised the idea of motels with locally sourced materials, an appropriateness of setting and an honesty in its combination of space, structure and surface.

Thompson, who actually worked there in the 60s says the building and its spatial repertoire, “makes me speculate on the permeability between ourselves and the buildings we inhabit: how they become embedded in us.”

There’s also a lovely story about a modernist Hobart house with a fascinating mystery attached to its architect Edith Emery, an Austrian émigré and polymath – a physician, teacher, linguist, writer, traveller and artist. And there’s a look at the work of acclaimed architect Enrico Taglietti and his acclaimed Giralang Primary School in Canberra. Along with an exploration of Glenn Murcutt’s contribution to what he calls “the architecture of the essential”, those so-recognisable buildings created on bushland sites focused on naturally coloured materials, like corrugated iron, used in their unaltered state.

Ross has become one of TV’s most persuasive presenters: authentic, congenial, and knowledgeable. He brings with him a moral conscience too, though he never bungs it on.

He never misses an opportunity to slip a gag in, or an appropriate defusing one-liner delivered almost by a kind of verbal sleight-of-hand. His passion though is the way that good design can create a sense of community, a sense of place, and offer, in difficult times, much needed, visions for our future.

“Many of the houses, buildings and people featured in this series have come into my life and their stories have ignited something in me,” he says. “Conversations, house visits, friendships and the connection of a belief in the power of good design has brought these people together on screen. Their stories are important in telling the story of why architecture matters.”

Designing a Legacy, ABC, Sunday at 7.30pm.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout