Think Elon Musk is nuts? The real enigma may be Twitter’s first boss

This account of the rise (and fall) of the social media platform says it was chaos from the start – thanks to its eccentric, ice-bathing founder Jack Dorsey.

It’s a strange business that although Elon Musk paid $US44bn for the social media platform Twitter – before arguably trashing it, along with his investment and global reputation – still nobody really knows why he wanted it.

Battle for the Bird, a definitive history of the site now known as X, can’t quite answer that question, either, but what it does is remind you that this is not just the story of one weird tech billionaire but two. And while it is Musk who today gets all the attention, the real enigma may be the guy who came first.

There are far bigger social media platforms than Twitter, and even today it has a usership of a fifth of Facebook, or a quarter of Instagram, or maybe half of TikTok. Being the hellsite of choice for most politicians and media, however, it has always punched above its weight.

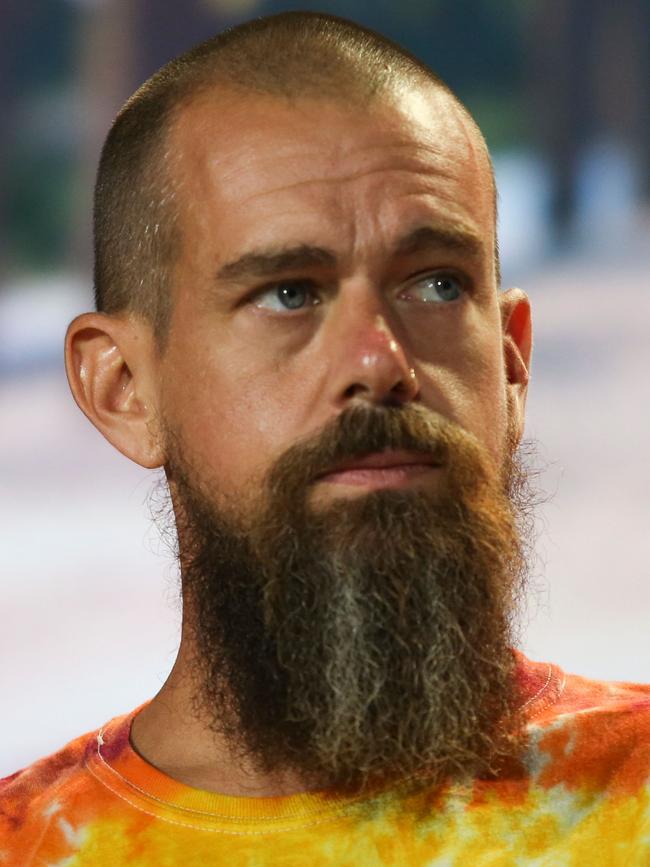

Jack Dorsey co-founded the site in 2006, when he was 29, and it was chaos from the start. Usage swiftly soared – there were 100,000 users within a year – but the commercial case was never clear and programming was shonky. Dorsey was the first chief executive, but was not convinced Twitter should even be a company, nursing a vague idea that it should be a protocol, perhaps more like email.

“On top of that,” Kurt Wagner writes, “Dorsey was still pursuing several other passions and hobbies, including a sewing class. He eventually hoped to make his own jeans.” Within a year, the board had kicked him upstairs, making him chairman instead.

In 2015, after years of corporate mayhem, he came back. By now Twitter was a global internet fixture, credited even with bringing about the Arab Spring. Yet advertising was patchy and strategy erratic.

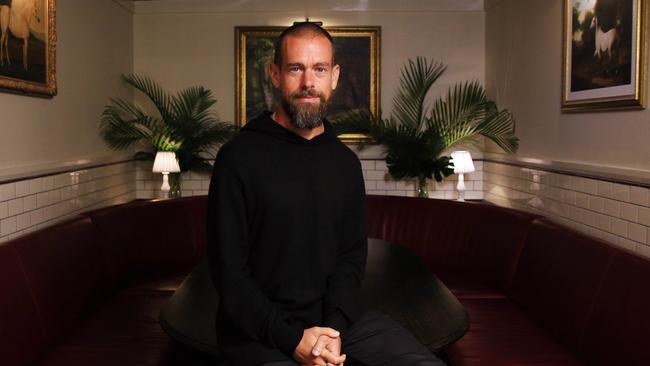

Quite a lot of the dysfunction, it seems, was just down to Dorsey being deeply weird. “He started taking cold showers and ice baths and used a barrel sauna to rapidly change his body temperature,” writes Wagner, a tech journalist for Bloomberg. The New York Times called him “Gwyneth Paltrow for Silicon Valley”. Summoned to Congress, he turned up in a strange, collarless purple shirt and with a nose-ring, looking like a hippy alien dentist.

Sometimes he would vanish on silent retreats. Another time, he turned up at a conference dressed as an astronaut.

Then Covid happened. During this time, the company fretted about medical disinformation. The banning, limiting and silencing of problematic users, which had already been increasing, stepped up a gear.

By the start of 2021 these bans finally extended to Donald Trump, after his tweets about the attack on the US Capitol on January 6.

Twitter wasn’t alone in shutting him down – Facebook and Instagram did too – but, despite being ultimately responsible for this decision, Dorsey wasn’t happy. And one of the main people he shared that unhappiness with was his friend and idol Elon Musk.

For his part, Musk had always been a prolific Twitter user. Eventually, he turned up at Twitter HQ as the new owner, carrying a sink, as a representation of the meme “let that sink in”. This, for anyone not familiar, is about as good as Musk’s jokes get.

The second half of this book is dominated by Musk, and the general theme is one of considerably more lurching chaos. Yet altogether, the narrative functions as a useful reminder that the madness didn’t start with him.