The woman still fighting for the rights of women and girls in Afghanistan

Sima Samar gives us a moving account of growing up as a girl in the often brutal patriarchy of Afghanistan.

An Afghan house is like an Afghan family – extended and sometimes complicated. Ours had three large windows facing south. The heat of the sun poured into those rooms when it was cold, and we could read and do our stitching by its light all day long.

The cooking room that my mother used in the winter months had a small alcove off to the side. In the summer, the cooking was done outdoors; whether inside or out, vegetables and meat were cooked over an open fire and milk was gathered from the livestock to be boiled into yoghurt, butter and cheese.

The main room in the house where the family gathered was lined with mattresses and cushions and had no furniture. We sat on these pads on the floor around the dastarkhan — a large rectangular oil cloth — to eat our meals. The food was served on heaping platters and in bowls in the centre of the dastarkhan, and everyone helped themselves to a meal that we ate with our hands. We also slept on the floor.

Our house had no running water or electricity. What’s more, it didn’t have my father. That’s the complicated part. He lived in a modern house about 550km away in Lashkar Gah in Helmand Province, with his second wife, Halima, and their children.

When I was very small, we’d all lived together in Jaghori: my sister, Aziza, my brother, Abdul, and two children my father had with Halima at that time.

They eventually had seven more for a total of nine children, which, when added to the three from my mother, made us a very large family.

I was a toddler when my father moved away with Halima, so I don’t remember the details.

My mother managed on her own.

She milked the cow herself and made delicious yoghurt and butter for all of us. She raised chickens and exchanged the surplus eggs for colourful threads and fabrics for her embroidery. She was so patient with me and would sit down with pieces of white cloth and lovely threads to teach me how to stitch and make a design.

My father came to Jaghori to visit us during the summertime, occasionally bringing his second wife and my other siblings. As a small girl I loved listening to my mother’s stories and piecing together the tapestry that was her life. She told me that she’d gotten married when she was very young, which was the tradition then.

I soon found out it was still the demand of some of the men and some of the mullahs who were part of the patriarchal system in our country and claimed that girls must be married before they menstruate.

My sister Aziza was therefore born soon after my mother had her first ovulation. Her second child, Abdul Wahid, was born three years later. I came along in 1957.

When I was six years old my mother took me to the mosque to study; there were about 50 boys in the class and only 10 girls.

Although my uncle had already started to teach me to read the Koran, my mother wanted more education for me, and the mosque was the place to learn to do maths and to write as well as read.

Although today we hear mullahs who are more politicised ranting and raving about an endless list of sins (mostly committed by women), the mullahs in those days had authority in the village but were not to be feared. Every village had a mosque and a religious scholar who was chosen collectively by the villagers; he could read and write, while most people could not.

The mullah at our mosque was a young man who soon taught me the love of learning that would stay with me throughout my life: doing maths was like playing games; books were like windows into another world; learning was a life-altering experience that thrilled me. I took to learning like a bee to flowers. I wanted to learn more and be better. Every Wednesday afternoon the mullah checked our lessons; if we hadn’t done well, the punishment was to be beaten with a stick. But I was never beaten.

Now when I think about those days, I’m drawn to what a happy and peaceful time it was; the only guns we saw were for hunting wolf or gazelle or bighorn sheep for food.

But by the time I was eight, I had learned about power relationships and expectations. It was very clear that girls and boys had different roles: girls could play with dolls; boys could play games outside.

A man could ride a horse, but a woman could do so only if the horse was being led by a man.

Girls should learn to do embroidery, cleaning and cooking. Boys could ride bicycles – although I used to take my brother’s bike when no one was watching and ride it myself. I was lucky: the high school I ended up attending was staffed by American Peace Corps volunteers, so the classes were coeducational, with male and female teachers and no boundary wall dividing boys and girls.

I was a voracious reader. Through books such Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables, I learned that other people didn’t live by the same strict rules that the people in Afghanistan adhered to. By the time I was 12, I knew I was a rebel, and that I could never accept my society’s patriarchal traditions.

I once heard a mullah say that every menses was a crime because an ovum had been wasted. When I questioned him, he said girls should be married at the age of nine or 10, and he started shouting at me for daring to ask him such questions.

I did well in my classes and usually came first or second, which was a very good thing. Because I was skirting the family’s rules almost all the time, I knew I had to stay on my father’s approval list or he would yank me out of school.

It was during my high school years that I became interested in joining the students seeking a better Afghanistan, with equal rights for all people.

However, there was a different development closer to home that took me by surprise. I was using my summer break to take typing and tailoring lessons when a marriage proposal arrived. My father reviewed the request and, to my enormous relief, abruptly said, “No.”

My sister Aziza, who had been married while still a child, died shortly after childbirth, and my father had said he would never again force one of his daughters to marry.

He told me that when I wanted to marry, I should tell him, and he would arrange it.

To be clear, in Afghanistan, the usual practice is for the family of the boy to approach the family of the girl with the proposal.

Sometimes the marital arrangement is made as a way to settle a dispute, at which point it becomes a forced marriage rather than an arranged one.

It was during my final year of high school that Abdul Ghafoor Sultani came into my life – first as a visitor to our house. He was the nephew of my second mother, Halima.

Ghafoor, as everyone called him, had spent six years studying physics on a scholarship in the USSR (several Afghan women were also given scholarships to study in the USSR) and was now a professor in the Faculty of Science at Kabul University. He was also a friend of my brother Abdul.

I was also preparing to write my final high school exams when I received a letter from Ghafoor proposing marriage.

The proposal was both surprising and somewhat confusing.

I didn’t know what to do. I wasn’t interested in getting married, but I was adamant about going to university.

I brought the letter to my brother Abdul Kayum to get his advice. He liked Ghafoor and agreed that this was my chance to go to university; he reminded me that our father would not allow me to go to university and live in a city away from home. I was honest with Ghafoor, as I didn’t want to enter this union with deceit. I told him that I could not be an obedient wife, but I could be a good friend. And I also told him that one of the reasons I wanted to marry him was to continue my studies. He promised he would do everything he could to facilitate that.

I knew he loved me, but somehow I had grown up understanding more about loyalty than love. I had both fondness and respect for Ghafoor and, what’s more, he offered me a rescue plan. And so, at the age of 19, I became officially engaged to Abdul Ghafoor Sultani, a 26-year-old physics professor at Kabul University.

After the wedding, Ghafoor and I rented a house from one of his colleagues; it had two rooms, a small kitchen and a bathroom.

We had to scrounge to find furnishings.

But starting our new life was fun. We walked together to university and came home together. We had an arrangement that ours would be an equal opportunity household; the chores, the cooking, the laundry, the cleaning, even the banking would be shared 50/50. Everyone called us the “50 per cent couple”; if I was out without him, or he was without me, they’d ask, “Where’s the other 50 per cent?”

I went out to the cinema with his sisters or my fellow classmates whenever I wanted and without asking anyone’s permission.

Life was not easy, as we had very little money, but we were happy. Our families, of course, kept asking us why there was no child.

We caved in to the pressure after two years of marriage.

Fortunately, I had an easy pregnancy. Of course, there was much talk about the sex of the baby – at that time, having a boy was preferable to having a girl, but I was just delighted to be pregnant and didn’t care either way.

Ultrasound was not available then, and so no one knew the sex of the baby in advance.

I was attending school on my due date.

I went home, and, all of a sudden, the birthing cramps began.

I gave birth to our son, Ali, right there at our house.

It was an April day in 1978 that our peaceful lives came to a sudden end. Classes were cancelled and Radio Kabul, the only radio station in the country, suddenly switched from regular programming to pumped-up patriotic songs.

As darkness fell over Kabul that night, the roar of low-flying fighter jets indicated that the rumours about a coup d’etat were probably correct. At 9pm, a radio announcement said everything was under control, which we interpreted as code telling us that the government had fallen to revolutionaries.

The next day the city was tense: most people stayed inside. The following night at 10pm the news declared that president Daoud and his family were dead and the revolutionary forces of the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan had taken over the country.

Over time, I began to believe that the mujahideen were the ones truly fighting for Afghanistan; we saw them as heroes and assisted their work wherever we could. We had long been advocates for human rights in Afghanistan. But when I heard that our friend Muhammad Akram had been arrested, I knew it could mean danger for us. I suggested to Ghafoor that we escape so neither of us would be arrested. He wouldn’t consider it. “When we got married I promised you that I would do everything I could to facilitate your education,” he said. “And now what I want more than anything is for you to get your medical degree. I’m not involved in any anti government activities; they won’t arrest me.”

A week later my world fell apart.

It was June 23, 1979. I was in my fourth year of medical school at Kabul University; our son, Ali, who was sixteen months old, was with my parents.

It was a bright and sunny Saturday. The rumour mill was busy, and we all anticipated danger. My sister, who was studying engineering at the university, even talked to me about what we should wear in case something were to happen. I decided on jeans, since I could run faster in them than in a skirt.

There was a loud banging at the door. When we went to see who was there, 12 men were standing outside, and as soon as the door opened six of them barged into our home.

The leader of the group was one of Ghafoor’s students. They said he had to go with them. I demanded to know where they were taking him. The student said, “Don’t worry, we’ll bring him back in a few hours.” I told him I didn’t trust him. He replied: “I swear to you I will.”

I grabbed Ghafoor’s coat and stuffed all the money I had, about 1200 Afghanis, into the pocket, hoping it might help him. “Wear your coat,” I said. “It’s a cold night.” It all happened so fast – Ghafoor was still wearing his nightclothes when the men pushed him towards the staircase of the house and then stood between us. He glanced back at me with a look on his face that I knew well – it meant take my words seriously.

“Don’t go looking for me,” he said. His eyes were pleading when he added, “It is too dangerous for you.”

I never saw my husband again. Neither did his little boy.

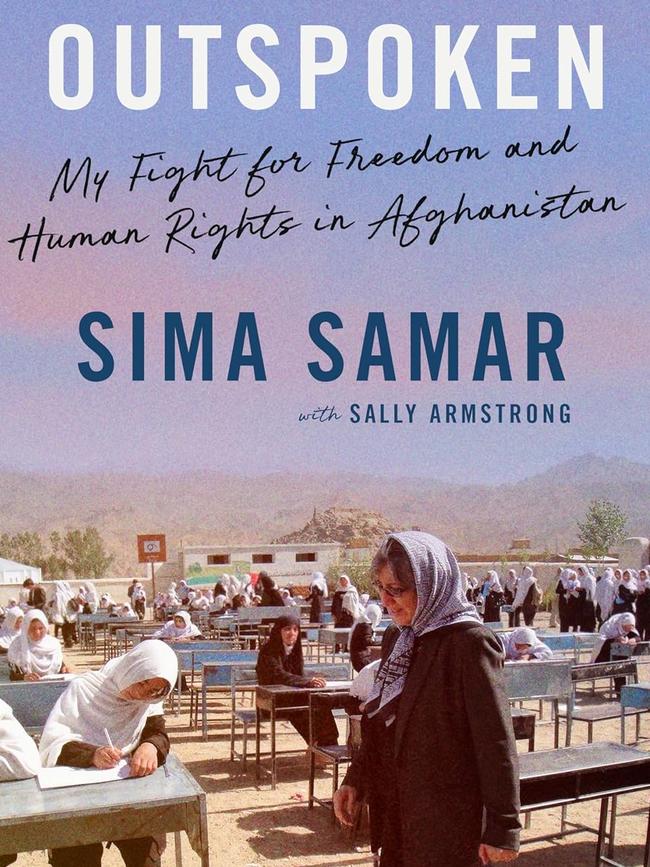

Extracted from Outspoken: My Fight For Freedom and Human Rights in Afghanistan by Sima Samar and Sally Armstrong (HarperCollins Australia), out now.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Sima Samar was born in Afghanistan and raised largely by her mother, who was her father’s first wife. She is today a doctor and human rights activist. While serving the Interim Administration of Afghanistan, she opened more than 100 schools and hospitals, and introduced laws to criminalise honour killings and human trafficking. She also worked to ban virginity testing and “bacha bazi” (the sexual exploitation of Afghan “dancing boys” by older men). She now lives in Canada.