The Whiteley scandal: Inside the art world’s unseemly side

The story of $3.6m of allegedly forged paintings is just as perplexing, and ultimately concerning, to the art world as Brett Whiteley himself.

For most of us, the art world seems cliquish and absurdly elitist, intimidating, and inaccessible. The mystifying language of so-called curators needs a translator in order to understand its complexities. The wealthy and powerful run the show, often anonymously. Certainly the power is not in the hands of the artists.

It’s a world shrouded in byzantine secrecy. Scandals involving forgery, money laundering, thefts, lapses in probity and unethical behaviour are quickly swept under the rug, and court cases rare.

Its unseemliness and unlovely side are compellingly on display in The Whiteley Art Scandal, a documentary telling the story of the greatest art fraud case in Australian history: the selling for $3.6m of allegedly forged paintings purported to be by famous Australian artist Brett Whiteley.

It’s a most unusual piece of true-crime TV — an account of a wrongdoing that was eventually seen not to have happened. Or did it?

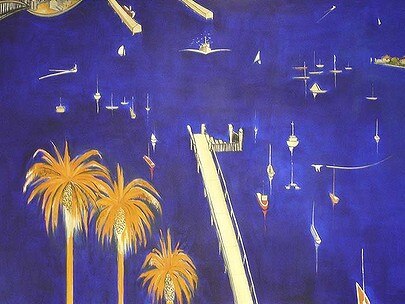

Art dealer Peter Gant and art conservator Mohamed Aman Siddique were accused of pursuing a joint criminal enterprise to create three paintings — Big Blue Lavender Bay, Orange Lavender Bay and Through the Window — in the highly discernible style of Whiteley, who died in Thirroul, NSW, from a heroin overdose in 1992. The pictures are so huge, so iridescent in colouring, and so difficult to transport, let alone carry up a court’s steps, they are almost characters in their own right. If only they could speak.

The Crown claimed Siddique painted the artworks in a small corner enclosure in his Easey St, Collingwood studio from 2007, and Gant then passed them off to unsuspecting buyers as original 1988 Whiteley paintings.

While found guilty, they were sensationally later acquitted after prosecutors said there was a good chance the pair might have been innocent of faking them.

The two-part series is from In Films and is directed by the distinguished documentarian Yaara Bou Melhem, who has made films for Dateline, SBS and the ABC. According to her biography, she has made documentaries that involved crawling through Syrian rebel-held tunnels, filming in lawless Libyan jails after the fall of Gaddafi, documenting disaster response efforts after wildfires, earthquakes and cyclones.

If that’s not too exhausting, she’s also explored taboo subjects such as youth suicide in remote Aboriginal communities, filmed with women escaping honour killings in Jordan, and followed doctors giving free health care in Nepal.

Making a film about Brett Whiteley must have been a doddle but his is a life that brought misfortune to many involved in its extremes.

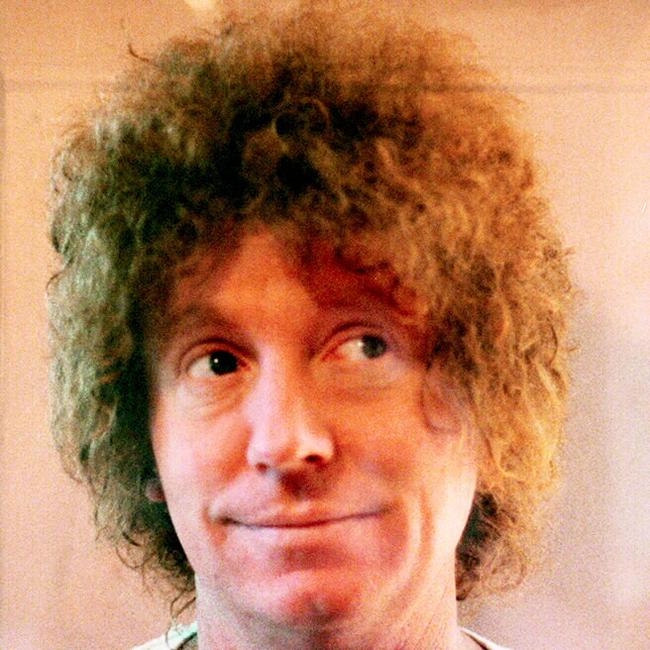

Whiteley was the mop-top sexy wizard of art, and the Australian public loved him for it: the white suits, the rag-top BMW, the lonely drug-purging bouts, the beautiful actress daughter, the sad-eyed addicted wife and the beautiful younger lover who so voluptuously resembled her.

We loved the bare bottoms on the beach in his paintings, the autoerotic touch, the idea of the artist as an act; Australians responded with unblinking enthusiasm to the energetic, vulgar, effervescent sexiness of his imagery. For us, despite all the drama in the painter’s life, his was the sunny spot in Australian art.

But the downside was making the unacceptable acceptable, desirable, and even glamorous. All his life he played to his publicity like a rock star and fed the Brett Whiteley myth with lust, alcohol, urgency, smack, overstatement and grief.

The story of the allegedly forged paintings is just as perplexing, and ultimately concerning, to the art world as Whiteley himself. And disturbing to the art world as many of its more clandestine dealings are revealed.

The series is “based in part” on Gabriella Coslovich’s well-received book, Whitely On Trial. The journalist followed the case for two years, reflectively examining the circumstance from every angle – from the creation of the artworks in a Melbourne art restorer’s studio through to the alleged $4.m deception and the trial’s controversial conclusion.

“There’s no way I was going to miss this case; I had to be there,” she says in one of the many discreet re-enactments, most abstracted – hands on paintings, shadowy court proceedings, a police van collecting the paintings, doors opening, kind of thing.

“This was my first criminal trial, and it was terribly exciting; there was so much more to this story than I had ever imagined.”

With Coslovich providing a narration of sorts, lively and often trenchant, Bou Melham manages to interview a cast of characters that would grace any legal thriller. It’s the sort of case Michael Connelly’s Lincoln lawyer would delight in embracing.

There are art dealers, of course, as well as art collectors, police investigators, a defence barrister, a prosecutor, gallery assistants, and Whiteley’s former wife, who admits early that she is an alcoholic and an addict. (She also has the best line – on seeing one of the paintings in dispute she says, “If it’s a Whiteley, it’s a very bad hair day.”)

It’s a little hard to keep up with the talking heads, though they are skilfully photographed by cinematographer Tom Bannigan, but Melham and her experienced producer, Ivan O’Mahoney (Folau), also have another graphic device to maintain narrative continuity. They use the drawings of Bill Luke, court artist for the trial, to show the links between the many individuals involved in the scandal. The sketches map the journey of the paintings and provide clever illustrations of those involved.

The essence of the story is the way the prosecution had to prove that that the investigation involved a premeditated case of art fraud, harder than it seemed as it proves. As Bou Melham shows through her interviews with some rather shady participants, the problem is not so much authenticity but the provenance of the pictures. That is the documentation that validates them, outlining the works’ creator, history, and appraisal value.

And it’s hard to pin down. Is it possible Whiteley could have actually painted them under the influence of heroin at a time when his estranged wife was absent?

And what to make, for instance of a bookbinder, Guy Morrell, who worked upstairs in Siddique’s art conservation warehouse in Melbourne’s Collingwood and the sequence of photographs he takes with a small digital camera of two paintings in progress, one orange and the other blue, in the highly recognisable style of Whiteley? Was this really the so-called “smoking gun” that would convict the alleged fakers? Then evidence emerges that they might be copies in fact of the original works, which is not illegal.

At times it’s hard to follow and Bill Luke is forced to work overtime with his many drawings and his “humorous observations of the trial”. But it’s an absorbing watch, the first episode filling in the backstory of the chain of events that leads to the sensational trial in Melbourne which provides the drama in the second episode.

At times it’s easy to be reminded of Fiona Bruce and Phillip Mould’s Fake or Fortune, that sees these amiable presenters, one a formidable UK journalist and the other a leading art expert, hunting down the provenance of various art works on behalf of their viewers. They crusade for the correct identification of would-be priceless masterpieces in a show that is part detective series – there’s a lot of CSI-like scientific wizardry as experts analyse brushstrokes and peel back layers of paint – and part travelogue as they trace the painting’s history and informative art history discussion.

Bou Melham’s two-part series is also an investigative mystery full of perplexing twists and people with shady characters from a world most of us would never encounter. As Tom Stoppard once said, “I know it’s a painting if it’s on a wall; it’s a sculpture if I can walk around it.” And Bou Melham stylishly exposes the greed and cupidity of that world, her series an interesting and entertaining addition to the continuing anxiety concerning authenticity and the way it is defined and applied.

The Whiteley Art Fraud, Tuesday, ABC, 8.30pm.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout