The truth about male ballet dancers

Do male dancers become aroused during the pas de deux? Are their jockstraps really padded? Wonder no more.

Having placed his subject, the rising 22-year-old ballet star Rudolf Nureyev, at ease with talk of literature, photographer Richard Avedon coaxed him to strip (“Your body at this moment should be recorded. Every muscle. Because it’s the body of the greatest dancer in the world”). The result, published after Nureyev’s death, is unforgettable: a ham hock hanging from a sprig of rosemary. While his rationale was intellectual, Avedon well understood the brief.

David McAllister OA, former artistic director of, and principal dancer with, the Australian Ballet – after winning bronze at the fifth Moscow International Ballet Competition in 1985, he went on to dance with the Bolshoi, Kirov, Georgian National and other legendary companies – also gets it. His second pointe-curious book, Ballet Confidential: A Personal Behind-the-Scenes Guide, doesn’t merely limit itself to the artform’s engrossingly complex history, but answers almost every question one would never, for fear of being #metoo-ed, ask.

For example, are male dancers’ jockstraps – otherwise known as dance belts, G-strings, supports, and thongs – padded? (Asking for a friend.) McAllister, who, judging from photographs, may, on at least one or 12,000 occasions, have been confronted by the same question, assures readers that this has never been the case; instead, a thick, artfully designed elastic undergarment that both prevents injury and “provides the dancer with a Ken doll–type bulge that does not give away too much information” is worn. (I imagine that, as he puts it, the “more lunch you have to pack”, the more winning the photographer’s analysis of contemporary American nonfiction at a shoot.)

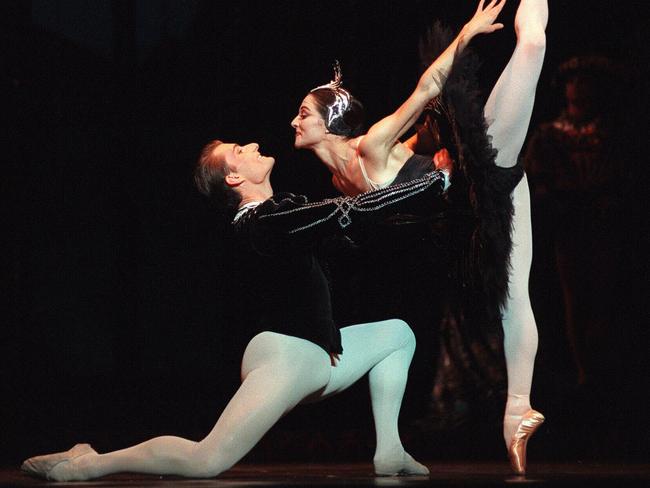

Notorious for their sexual appetites, male dancers – like all athletes, at ease with their bodies and physically eloquent – do not, according to McAllister, become aroused during even the most emotive or erotic pas de deux (“The sheer panic of getting the technique right, particularly as a young dancer, is enough to quell any hormonal engagement”). First, there is the responsibility of keeping the female partner vertical while she has a leg extended in any position, a task demanding years of training. Then comes the shoulder lift, a feat involving the superficially serene management of 10 or more metres of stiff, layered tulle fabric projecting half a metre or so from the ballerina’s hips as she is hoisted upwards in a fluid movement.

The “mother of all required moves”, however, is the overhead lift (“enough to spark fear into both participants”). McAllister, whose thighs were, in his youth, magisterial – he had a native talent for leaping – spent weeks doing push-ups at night in an effort to develop his twiglike arms. As a result, his first full arm lift was exhilarating – so much so that once his partner had finally “ascended skyward”, he had absolutely no idea how to put her down.

Known for his powerful physique, McAllister was, it appears, never prey to the life-threatening eating disorders that have plagued his ranks for over a century. He blames the pressure on female dancers to be thin on the despotic 20th century ballet master and choreographer George Balanchine, who transformed ballet “from the lavish narrative spectacles witnessed during his training to a sleek, abstract and modern form that fit so perfectly into the post-war ascendancy of his adopted country. This in part was achieved by stripping the stage and the dancers of any excess design and focusing solely on the physicality of the choreography. This was the catalyst for his desire to have his dancers achieve even longer and more sinuous lines, as there was nowhere to hide. To attain this sculptural effect, it is said that he wanted his female dancers to look the same facing front as facing back. He believed that the “ballet was a woman, and in his eyes it seemed that a woman was at her best when you could see bones”.

Research also suggests that the same qualities which define great dancers – a desire for order, perfectionism, rule-governance, symmetry – are aligned with a significant predisposition to eating disorder. Backstage at the Australian Ballet some decades ago, I remember wondering not only at the rigour of their training but at the hollowed, caffeine-fuelled frailty of the female dancers.

Recently, psychologist Linda Hamilton observed that 50 per cent of dancers suffer an eating disorder. In part, this could be due to predisposition – perfectionists like to exert control in all things – but ballet culture is the matrix of the problem.

Gelsey Kirkland, a New York City Ballet principal ballerina who, like many dancers, abused drugs and dieted to dangerous extremes came to represent this desire among female dancers in particular for ballet-standard “perfection”. At the time, McAllister remembers, there was a significant spike in injuries caused by bone fragility and general muscular debility.

The rise of dance medicine and research into the dangers of extremely restricted diets have, McAllister writes, finally started to change his world: “Dancers today are given evidence-based information about how to maintain a healthy diet while building strength and fitness as part of their vocational training. We have learnt much from elite sports where diet is part of the regimen that allows for high performance while maintaining a strong, agile physicality.”

To paraphrase Queen Camilla, Ballet Confidential: A Personal Behind-the-Scenes Guide reads as easily as falling off a chair. McAllister, like Avedon, addresses the reality of his subject without flinching, transforming what could have been rote to a rich, romantic, and sexually charged celebration.

Antonella’s new book is Apple: Sex, Drugs, Motherhood and the Recovery of the Feminine. Follow her on Instagram.

Ballet Confidential: A Personal Behind-the-Scenes Guide

By David McAllister

Thames & Hudson Australia, Nonfiction

256pp, $34.99

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout