The Troubles are always with us, a new TV series shows

Based on the remarkable book of the same name, Say Nothing speaks loudly about the radicalisation of one woman and the murder of another in Northern Ireland.

“When I go out looking for a good story, I almost never find one,” says Patrick Radden Keefe. “Instead, the really good ones tend to fall in my lap. In 2013, I was reading The New York Times and came across an obituary for the first woman to join the IRA as a frontline soldier – Dolours Price. I was fascinated by Dolours, and what her life could teach us about the romance and the costs of radical politics.”

Five years and seven trips to Northern Ireland later, and after interviewing over a hundred people, the New Yorker staff writer published Say Nothing, his acclaimed work of narrative nonfiction about the abduction and murder of a Belfast woman called Jean McConville in that benighted city in 1972.

Subtitled, A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland, the book is not only an inspired chronicle of “three decades of appalling bloodshed and some 3500 lost lives”, also known as The Troubles, but was applauded as an emotionally devastating tale of collective denial. And, as suspenseful as a detective story, it is empathetic to all sides at various points in the retelling.

The Troubles were the four-decade-long conflict in Northern Ireland. Loyalists, protestants identifying as largely British, and Catholics, who wanted Northern Ireland to leave the United Kingdom and join a United Ireland, went to war in a political struggle fuelled by historical events.

A ring of steel surrounded the centre of Belfast after the British intervened as The Troubles became Europe’s longest-running conflict. Belfast witnessed many explosions and assassinations. The city centre was entirely cordoned off, while war-torn images made the city infamous around the world.

Keefe says his book is about “how people become radicalised in their uncompromising devotion to a cause” and how individuals and societies make sense of political violence “once they have passed through the crucible”.

Nick Hornby said it was one of the “greatest literary achievements of the 21st century”, and the book has received many such accolades.

It confronts the way the past simply won’t go away, Keefe says, no matter how much it’s ignored, that there has been no reckoning and that something in Irish culture allows for certain things to go unspoken.

His title comes from Seamus Heaney’s 1975 poem Whatever You Say Say Nothing: “Where to be saved you only must save face/And whatever you say, you say nothing.” Keefe’s book has now been turned into a TV series by Joshua Zetumer with Keefe acting as an executive producer.

Zetumer has written on several global box office hits, including Robocop and the action thriller Patriots Day about the Boston Marathon bombings in 2013. Establishing director is Michael Lennox, born and raised in Northern Ireland’s County Antrim, who most famously directed all three seasons of the Emmy-winning comedy Derry Girls, also set during The Troubles.

The series traces many of the prominent moments of the conflict though the lives of various IRA members, looking at how they were affected emotionally by the IRA’s single-minded quest for peace. And the cost of speaking out.

It’s centred around McConville’s shocking abduction from her home in the Divis flats on the Falls Road after she was accused by the IRA of passing information to British sources, simply because she was a protestant who married a Catholic.

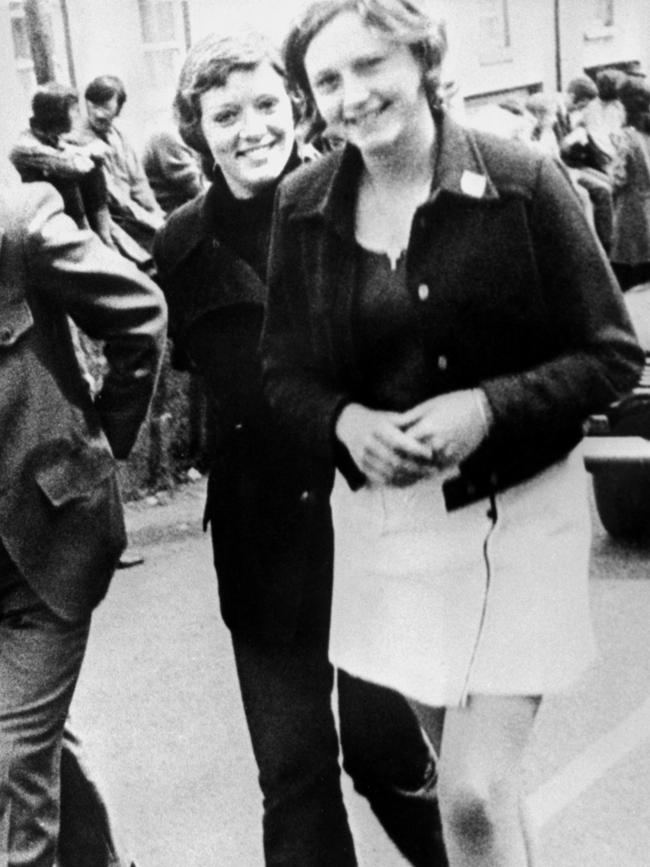

Intertwined with McConville’s story is the parallel narrative of IRA militants Dolours Price and her sister Marian, both of whom became involved in Republican women’s groups, then eventually, the Provisional IRA.

Dolours is played by Lola Pettigrew and Marian by Hazel Doupe, and the show follows them across four decades from idealistic teenagers attending peaceful protests to the intense young women known as “The Sisters of Terror”. Maxine Peake is the older Dolours, wry and saddened with regret. All are superb.

In March 1973, the sisters and other IRA members detonated car bombs at four locations in London, including the Old Bailey and a British Army recruiting centre. They were arrested while returning to Ireland. Both were convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment. While behind bars, the Prices went on a hunger strike, demanding repatriation to Northern Ireland; they survived after being forcefully fed by prison guards.

“The goal of the show, kind of one of the core ideas, is that we’re trying to show both the seduction of radical politics and also the cost of those politics,” Zetumer says. And Say Nothing is really about consequences and how they are dealt with, but it also plays with our sense of righteousness, and how we care for characters who do dreadful things.

This is something that Zetumer and his colleague dealt with as they wrote the script. “You are thinking about a character, and you’re trying to psychologically get under their skin, and then all of a sudden they do this thing that you think is horrific: putting a bomb on a crowded street,” he says. “And how do you reconcile your feelings about them? Everybody was on a sort of emotional roller coaster, just trying to write the show and trying to come to grips with how we felt about the characters.”

The series opens in 1972. Belfast is a city protesting its protestant values with raucous bigotry: there are civil rights protests, shootings, security checks, no-go areas patrolled by British troops, and an increasingly visible IRA planting bombs and staging robberies. There is major rioting on both sides of the religious divide.

A sarcastic narration begins the story, the episode called The Cause. A woman’s voice, (we learn later that it belongs to Dolours), narrates with a slight mocking tone.

“The thing about Irish people is that they’ve been arguing over the same shite for 800 years,” she tell us. “See, it used to be that this was our island until the British took it over. The Irish tried to fight them out but couldn’t quite finish the job so instead the British kept the top part for themselves and then the IRA has been fighting a bloody battle to reunite the country ever since; some die by the bomb, some by bullet; others simply disappear.”

Then Lennox’s cameras take us to Divis Flats, a housing complex in West Belfast, and the home of Jean McConville, a 37-year-old widow and her 10 children. As the family settle down for the evening, there is a knock at the door. A gang of masked intruders burst in and McConville is violently pulled out of the small apartment. Her last words to one of her older sons are, “Watch the children until I come back.” She never returns.

Some 29 years later, we are in Dublin. Dolours Price (now played brilliantly by Peake) settles in front of a cassette recorder to make her contribution to the Belfast Project, run by former Irish Republican Army member Anthony “Mackers” McIntyre (Seamus O’Hara). His idea is to gather testimony about The Troubles and develop an oral history, the tape to be secret and confidential. “The whole sordid story?” Dolours smiles wickedly.

And we are taken back to Belfast and follow the radicalisation of the Price sisters, the family staunch Republicans. The girls are the grandchildren of their Aunt Bridie (Eileen Walsh) who lost her eyes and hands in a bombing, handling IRA explosives. And their father Albert (Stuart Graham), is a former IRA member, having served eight years in prison, fond of telling the girls “The armed struggle, that’s the way”.

They involve themselves in peaceful protests, but their resolve hardens when they are beaten in the Burntollet Bridge incident of 1969. Participating in a march from Belfast to Derry, inspired by the Selma to Montgomery marches in the US led by Martin Luther King, the protesters are attacked by Ulster loyalists armed with clubs and iron bars. They are allowed to do as they like by the police.

It’s a horrible, frightening sequence, a setpiece superbly directed by Lennox, and it’s easy to understand its radicalising effects on the Price girls. (His direction, like the performances, compelling and authentic, is not only visceral but enlivened by startling moments of character comedy.)

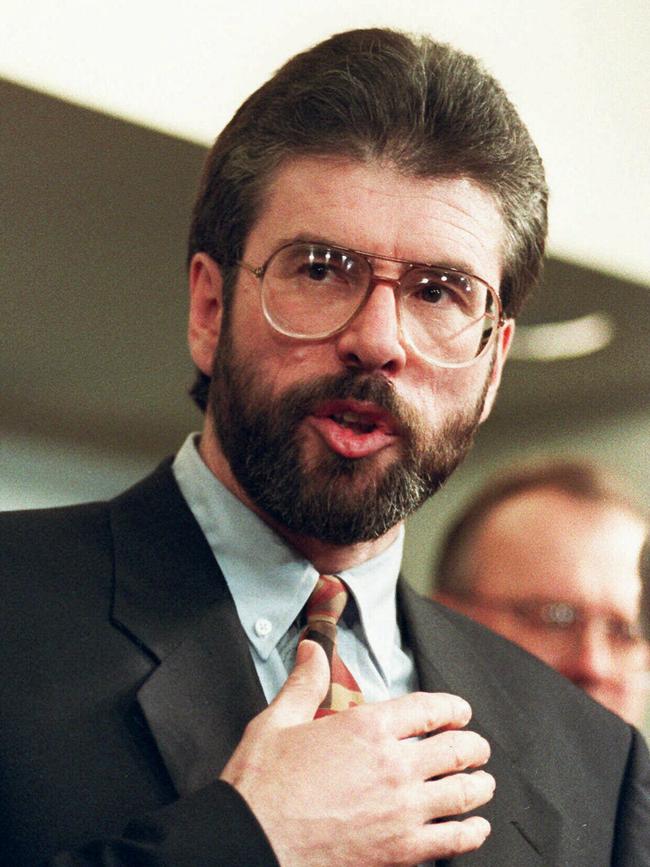

From this time on, led by Dolours, they are determined to do “what the boys are doing”, not content to “only be good for rolling bandages and making f..king tea”. Dolours is determined to “rewrite the fight”, the “women’s army” to be part of it. She is recruited by a youthful Gerry Adams (Josh Finan), now, of course, a prominent Irish politician, then, according to the drama, ambitious and merciless leader of the IRA.

The series opens with a title card saying it’s based on a true story, only to conclude each episode with a carefully worded disclaimer. “Gerry Adams has always denied being a member of the IRA or participating in any IRA-related violence,” it reads.

It’s obvious that what Keefe calls “the sulphurous intrigue of the past” still has quite a hold and that there is still a reflex to stifle debate about just what happened during The Troubles.

Say Nothing streaming on Disney+

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout