The tenderness of two lovers in Auschwitz

There is an Australian link to one of the most remarkable stories of human kindness to emerge from Auschwitz.

The erasure of three percent of the global population over five years began with language. Then slurs. Then workplace discrimination. Disseminated lies. Graffiti. The repackaging of abuse as justified. When verbal contempt is normalised, violence inevitably follows.

Set in in pre-war Czechoslovakia and Poland, Lovers in Auschwitz: A True Story opens on this - initially casual – demonisation of Jews. Author Keren Blankfeld, an American journalist, deftly documents the Nazis’ incremental construction of culturally unsafe spaces for the Jewish community.

“So many Jews refused to believe that the horrifying actions of thriving Nazism reported in Eastern Europe would reach them,” she writes, “but the undercurrents of anti-Semitism that had permeated the region for centuries only intensified.”

Shops run by Jews were vandalised. As the police did nothing, antisemitic attacks surged. Hopelessness began to set in. The narrative builds on the horror, detailing how the impecunious dysfunctional marginalised used the suffering of the Jewish community as a springboard to power. Heinrich Himmler, for example, “a slight, bespectacled chicken farmer, worked his way up through propaganda and intelligence-gathering roles. In 1929, he was promoted to national leader of the SS. In his hands, the SS grew into a multipronged beast. By 1940, it controlled the Nazis’ main vehicles of terror, including the Gestapo … as well as concentration and extermination camps.”

This, then, was the environment in which Zippi Spitzer, a lively, middle-class Czechoslovak Zionist, came of age. By the age of 21, she was a skilled graphic designer. Her handsome Jewish fiancé Tibor Justh, a member of the Czechoslovak resistance, had two goals: the elimination of fascism, and helping refugees escape. To this end, he provided them and Czechoslovak fighters with forged documents and transport across borders to safety.

Tibor was beheaded by Nazis in 1942. Incapacitated by fever in Auschwitz at the time, Zippi didn’t know.

On her arrival at the camp, Zippi, along with all the other women, had been ordered to strip off. Genitals and anuses were roughly searched for hidden jewellery. The women were then blasted with disinfectant through hoses. Bodies shaved and heads sheared, they were “no longer human; they were cattle, being sterilised for slaughter.”

The uniforms they were forced to wear were caked with the blood of former owners or, in some cases, perforated with bullet holes.

Indoor workforce units – kitchen duties, sorting and mending uniforms, typing up death certificates, and so on – were coveted; the outdoor work was difficult to survive. Digging drainage canals in swampland. Cleaning muddied bricks with bare fingers. Tearing down abandoned houses and building barracks, again with bare hands. The guards amused themselves by forcing female prisoners to pointlessly carry heavy rocks back and forth, or to clamber atop bombed buildings and throw bricks down on their fellow prisoners. Many died.

Zippi, like others who survived, “had to be stone.” Upon discovering she had talents they could exploit, the Nazis put her to work drawing meticulous diagrams of the camp. For years, she secretly drew a copy of each diagram to keep as evidence of their inhumanity. It was at this point that Zippi met David, a 17-year-old Polish Jewish prisoner with an unusually beautiful singing voice.

When they could, they began spending time together. Sometimes, Blankfeld writes, they even laughed. Music became a species of portal through which they could escape the unspeakable. “And they kissed, always so tender. It was surreal, having these brief moments, these lulls.”

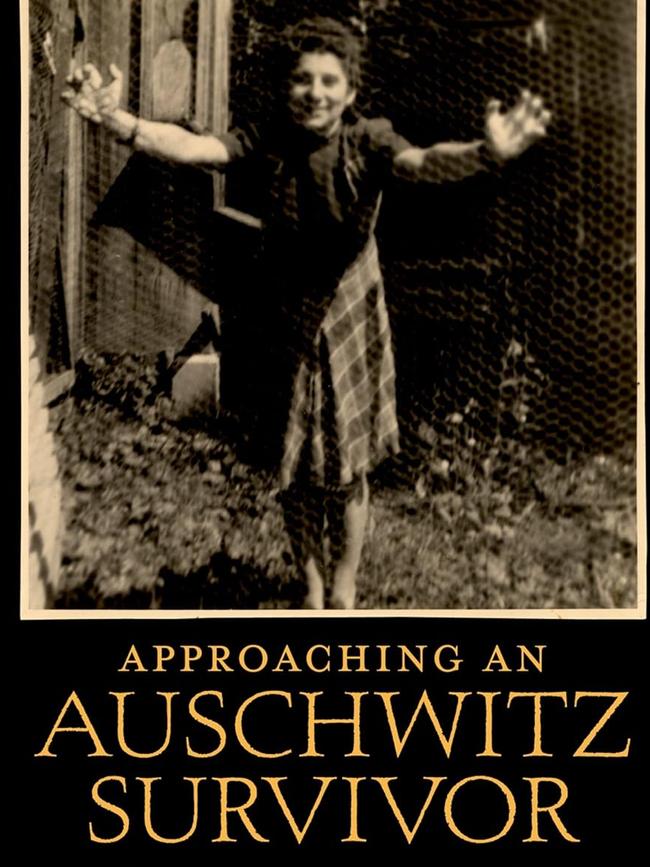

They promised that they would try to find each other if they survived the war, and we know that Zippi survived Auschwitz, and ended up in a displaced persons camp, where she met, and ultimately married, the chief of security, Erwin Tichauer, who in time became a professor of bio-engineering at the University of New South Wales, and at New York University. She also became the subject of an important academic text, Approaching An Auschwitz Survivor: Holocaust Testimony, in which she was interviewed by five different academics, as they sought to piece the Holocaust together. She was close to Sydney Holocaust Museum historian, Konrad Kwiet, who had survived the war as a child. He later became a consultant to the investigation unit, established to find Nazis who had fled to Australia. But she was already dead by the time Blankfeld set out to tell her Auschwitz love story.

There is the sense that the affair was less about passion than it was about the two prisoners enabling each other to endure a terrestrial hell. Secretly, Zippi, whose position afforded her unusual privileges – some access, limited freedom to roam, a voice of sorts - saved David’s life on five occasions. The most moving moments of the book are near the end, when David finally finds Zippi – she made it to ninety-eight - and visits, with his grandchildren. They’d barely spoken for seventy years. He had questions, and she had some answers.

Ostensibly a love story, Lovers in Auschwitz: A True Story, then, is more of a testament to the restorative power of tenderness. This should have been Blankfeld’s emphasis, if only because the idea of romance in a death camp - with its ever-present veil of human ash, and the stench of burning flesh - between two emaciated, traumatised people is repugnant. The love between Zippi and David was purer, closer to a love for life itself. In the end, their real gift to each other was hope.

Antonella Gambotto-Burke’s latest book is Apple: Sex, Drugs, Motherhood and the Recovery of the Feminine.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout