The strange story of Captain Arthur Phillip and Bennelong, the man he kidnapped

Kate Fullagar rejects the idea that British ‘beginnings’ are bound to be Indigenous ‘endings’. That’s why she opts opts to write the history of Bennelong and Captain Arthur Phillip, his kidnapper, backwards.

The quest for decolonisation in settler societies has introduced the imperative for “truth” in the history of relationships between settlers and Indigenous peoples. Historians know that historical truth is slippery and nuanced – but don’t we have facts? But then, analysis and interpretation of the forensic kind might show that apparently settled truths contain no facts at all.

Colonial records are written by elites to suit their own purposes. History making at its best is painstaking, through all phases of research and writing, and we can only ever really hope to get a glimmer of the ways in which people lived. Our ancestors were not like us – not in language, culture, morality, ethics – in any way at all. People from another cultural base are different yet again. The past indeed is another country, and the people who lived there are foreign in the widest possible sense of the word.

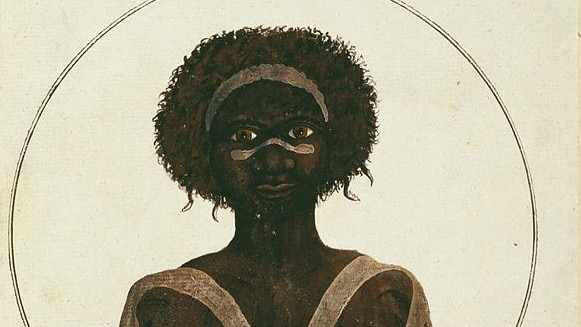

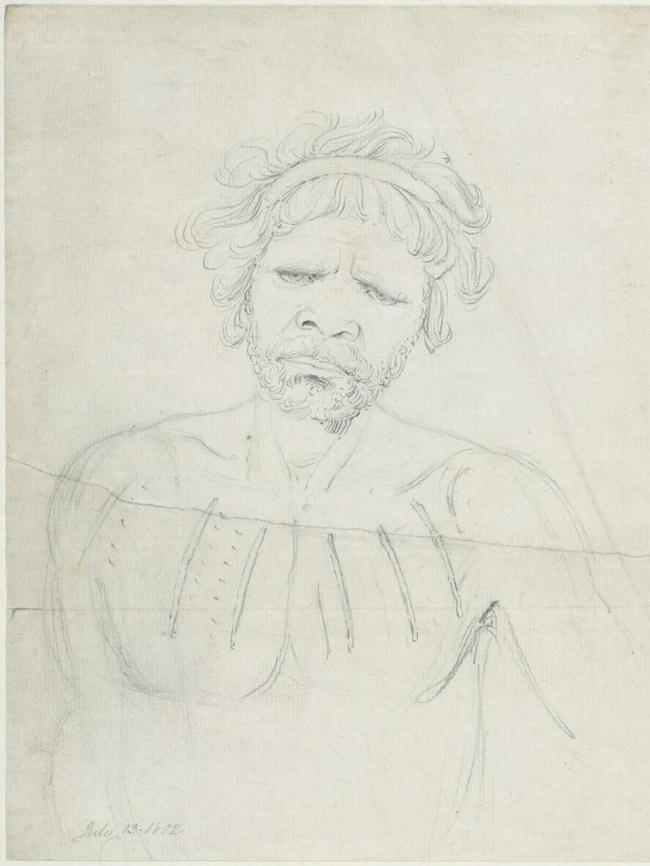

This needs to be kept in mind when considering the foundational relationship in the development of the Australian nation – that between Captain Arthur Phillip of the British Royal Navy – who spearheaded the annexation of Aboriginal Australia when he sailed into Botany Bay, NSW in January 1788 – and the Aboriginal man who happened to be kidnapped by him, Bennelong.

For the first time, a joint biography of the two men has been published. Their relationship was, we are told, pivotal to the development of the Australian nation; they were the “colonized, and the colonizer”. Bennelong has thus far been defined by his relationship to Phillip and the British, through their eyes. While he was there when Phillip was speared in Manly, observers did not understand why. While he did not take part in the attack it can be explained as being instigated by him and his elders as a payback for Phillip’s kidnapping and imprisonment of him.

Nonetheless he lived for a time in a specially-built hut on the governor’s property. He sailed to England with Phillip where he was treated with great hospitality and generosity.

Intriguingly, against the commonly understood history, he was not presented to the court of George III. The author of this new work, Kate Fullagar unravels the evidence as to how and why.

Much has been made of the decline in his health upon his return, his taste for liquor, and his early death that became a metaphor for the “decline” of the whole of Aboriginal Australia.

Fullagar has an impressive grasp of the colonial history of the British Empire, especially in respect of the developing relationships between colonists and Indigenous people. Previous publications explore relationships that overcame lingual, social, economic and cultural differences. She is impressed by the essential humanity of all peoples who seek to bridge these gaps and she interrogates long-held opinions often challenging them.

Further, Fullagar’s approach makes for a rich and exciting history telling. In her new book, she aims “to honour each man’s legacy, to gain deeper knowledge about the roles they played, (and) to understand the history of modern settler-Indigenous relations in a fresh way” by intentionally moving away from western history telling methodologies. Fullagar seeks to disrupt the historiography of progress that feeds into the colonialist tropes of the all-conquering white male and the naturally inferior, fading Indigenous man. She rejects the idea that British “beginnings” are bound to be Indigenous “endings”. To do this, she experiments with a way of disabling a “forwards moving narrative style” by “turning it on its head”.

Astoundingly, at least to my mind, she therefore opts to write the history of Bennelong and Phillip backwards. This is the “history unravelled” in the subtitle of her book: a brave, audacious and exciting idea that has the reader thinking deeply about the meaning of history and the role it plays in our lives. I can see how effective this would be for the truth telling process in Aboriginal history per se.

I was immediately interested in this book, and in reading, I found myself thinking constantly about whether the approach worked. I got caught up, at times, wondering what happened before the particular section I was reading, because obviously it was going to be revealed after, as I read further into the book. Sometimes the text had to foreshadow previous events to enable the reader to understand what was happening but Fullagar deftly manages this hurdle.

As history, this book does not disappoint: it is satisfyingly originally researched. It also introduces the historiography of the relationship between Phillip and Bennelong that established this relationship as foundational. As Fullagar tells it, the various analyses of this relationship reflect the changing tenor of the times and the positioning of the person who wrote it. Historians have beliefs and agendas (in truth, many histories tell us a great deal about the historian). To my mind, Fullagar’s position is ethically scrupulous, and highly objective in research and exposition, while being subjective in effect. Her book is a true reflection of contemporary progressive liberal values.

There were other relationships in the early days of the colony that were potentially as foundational as the one between Phillip and Bennelong but they were not so deliberately documented. This was the relationship that would inform the British of their political position vis a vis Aboriginal people, including whether to pursue treaty with them.

Other early colonies have romanticised the relationships between white men and Indigenous women, for example John Rolfe and Pocahontas (who was also a captive) in the fledgling Jamestown, Virginia (1607) and Hernán Cortéz and la Malinche a Nahua woman (enslaved) in the newly conquered Mexico (1519). These relationships also serve to celebrate the mestizo – the mixedness – of the new colonies as foundational to nation building. Not so in Australia, where there was a wariness about treating too seriously or examining too closely the truth about the inhabitants of rez nullius when there was no immediate imperative.

Fullagar’s history serves to slow down the history telling in such a way as to underline the essential humanity of each of these men, page by page. People from disparate cultures and societies who nonetheless shared a deep regard are worthy of being the founders of the nation state. There is something about this relationship that informs a quintessentially Australian sociality that can be teased out even further. This work also opens up new historical questions – some that can be informed by anthropology, some that can be informed by a transnational Indigenous lens – in the way that only the best of histories do.

I recommend this as a book that carries us much further on the journey to a reconciled future – and a delicious read to boot.

Victoria Grieves Williams PhD is Warraimaay and an historian.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout