The Phoenix Years: Madeleine O’Dea praises China’s free spirits

The Phoenix Years is required reading to understand how China has stumbled repressively through the past four decades.

In the past half-dozen years, at least three journalists of Australian origin or based in Australia have written first-class books about contemporary China. The first was Richard McGregor in 2010. The second was this newspaper’s Rowan Callick in 2013. The third is Madeleine O’Dea with The Phoenix Years. O’Dea’s is easily as good as the other two and trumps (if one can now comfortably use that verb) all mealy-mouthed apologetics for the repressive China of Xi Jinping.

McGregor’s The Party: The Secret World of China’s Communist Rulers was a brilliantly incisive expose of the huge Communist mafia that holds the world’s largest country under its thumb. It illuminated the structure and practices of the Communist Party in the era before the ascension of the overweening premier princeling Xi, under whom many chickens are coming home to roost.

Callick’s Party Time: Who Runs China and How updated McGregor’s work and provided readers with a wonderfully judicious portrait of a nation teetering between maturing as a modern state and stumbling into an era of renewed tyranny and possibly confounding conflicts.

O’Dea, who spent more time in China than either of the others has done, gives us a beautifully crafted and immensely readable book that moves back and forth between the narrative of historical events and the personal stories and artistic endeavours of some of contemporary China’s most imaginative and free-spirited citizens.

The Phoenix Years is required reading for all those who seek to understand how China has stumbled repressively through the past 40 years and how its finest citizens have persisted in trying to imagine a better, freer China. In interweaving the macro-economic and political with the personal and artistic, O’Dea does not put a foot wrong.

The book is well-paced, vividly written, based on deeply enriching personal encounters and observations and grounded in completely sound scholarship. Those who keep repeating the weary and fallacious mantra that Chinese culture is incompatible with democratic norms and that the Communist Party, instead of being criticised for human rights abuses, should be held in awe for ‘‘lifting hundreds of millions of people out of poverty’’ in record time, need to have this book thrust under their noses.

O’Dea worked for the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet before moving into journalism. She was Beijing correspondent for The Australian Financial Review in 1986 and later worked for ABC television. As she tells us early in the book she ‘‘was there for the ‘big story’, in the 1980s, of how the opening up of China was revolutionising its economy’’. She was there again and again in the 1990s and the 2000s.

Reading her book, I confess I more than once found myself reflecting that I should have become a journalist in China instead of an intelligence analyst charged with thinking about it. She was able to travel far more widely doing her work than I was ever permitted to do in the course of mine. Such are the bizarre constraints of the secret intelligence world.

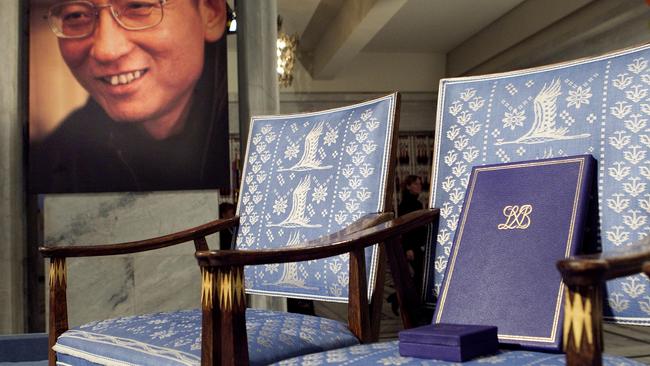

It is immensely refreshing to read O’Dea’s well-informed and forthright defences of Wei Jingsheng and Liu Xiaobo, whose lengthy incarcerations by the Communist Party for their principled, articulate and peaceful democratic dissent constitute a damning indictment of the Chinese regime. She tells their stories and quotes their words in context. That is good to see. Their warnings, about dictatorship coming back if the party refused to open the path to political reform and liberal democracy are being borne out under the neo-Maoist Xi.

As O’Dea observes:

The intense crackdown on China’s civil society, which began with the ascension of President Xi Jinping in late 2012, is now in its fourth year and shows no sign of slackening. Instead, an ever widening circle of people is being caught up in a campaign to silence alternative voices. In July 2015 a major police operation targeting China’s rights lawyers was launched across the nation. More than 300 people were picked up for questioning and 19 were charged after months in secret detention. The severity of the charges shocked even seasoned observers of China’s human rights record.

She points out that the state conducts surveillance, censorship, repression and the strangling of critical debate to an extent that is both extraordinary by Western standards and profoundly counterproductive from the point of view of China’s wellbeing and further development.

The soul of the book, however, breathes in her account of the lives and artistic endeavours of a range of people whose names are almost certainly unknown to more than a small circle of Australians who have paid attention to Chinese cultural affairs, even in the diaspora, over the past generation: Huang Rui, Zhang Xiaogang, Gonkar Gyatso, Aniwar Mamat, Guo Jian, Sheng Qi, Bei Dao, Mang Ke, Cao Fei, Jia Aili and Pei Li, all born between 1952 and 1985.

The link between the two themes or strands of the book is formed early on, where O’Dea writes that ‘‘when China’s most famous dissident, Liu Xiaobo, winner of the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize, was writing about what influenced him most deeply in his formative years, he cited the poetry of Bei Dao and Mang Ke and the art of Huang Rui’’.

As I read this book, I found myself highlighting numerous passages indicative of the soundness of the author’s knowledge, the maturity of her prose and the poignancy of the stories she tells. There are many passages I would have liked to quote.

But above all, I found myself thinking that O’Dea has done us all a great service by bringing together the disparate stories of her artists and showing how their creativity has been a constant struggle against regime repression.

That is the direct testimony of these free spirits, for whom the death of Mao in 1976 was a liberation, the 1978 Democracy Wall a springtime of freedom of expression, the open-minded general secretary Hu Yaobang a hero and the brutal crushing of the popular democracy movement in June 1989 a defining moment. Their vision for China’s future should be ours.

Paul Monk is the former head of China analysis in the Defence Intelligence Organisation and author of Thunder from the Silent Zone: Rethinking China.

The Phoenix Years: Art, Resistance and the Making of Modern China

By Madeleine O’Dea

Allen & Unwin, 360pp, $34.99

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout