The Mars Room delves into loss of self within confines of prison life

That the self is extinguished by prison means inmates are caught in a catch 22.

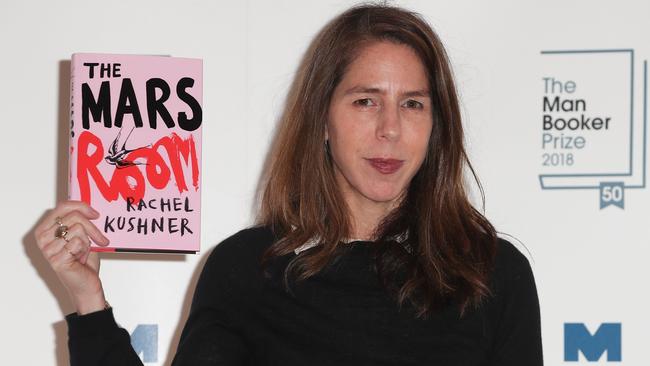

Rachel Kushner marches to the beat of a different drum than her American contemporaries. While they zag towards autofiction, she remains committed to exploring otherness and contexts. Her two previous novels exhibited an attraction to politicised milieus beyond literary NYC and LA: foreign countries, extremist ideologies, edgy people.

Telex from Cuba (2008) is set in the sugar plantations and nickel mines of eastern Cuba during the Batista dictatorship of the 1950s; the preoccupations of The Flamethrowers (2013) include motorcycle manufacture and Italy’s Years of Lead.

The Flamethrowers sees land artist “Reno” on her Moto Valera ’77 roaring past a Greyhound with its windows meshed and blacked and the words NEVADA CORRECTIONS on its side. The start of The Mars Room takes us inside one such mobile prison. It’s heading from a Los Angeles County correctional facility to Stanville women’s prison in the western Sierra foothills. Cuffed and chained on this bus is 29-year-old stripper Romy Hall, who has just received two consecutive life sentences plus six years for murder.

The Mars Room is, largely, Romy’s story — from her early days hanging out in Sunset District with Eva, “one of those girls who always had a lighter, bottle opener, graffiti markers, flask, amyl nitrate, Buck knife, even her own sensor remover”, to her time working at the Mars Room — which, if a reviewer on Goodreads can be believed, is “not a middling or mediocre strip club but definitely the worst and most notorious, the very seediest and most circus-like place there is”.

The bulk of the novel, however, is given over to Romy’s experiences in Stanville prison. Kushner is very good at detailing this highly codified environment with its official and unofficial rules and consequent behaviours. Guards are friend-zoned, runners are procured, contraband is smuggled, sexual appetites are satisfied alone or with others and boredom is rife. Bottom line: there’s no trust because everybody has an angle.

Like The Flamethrowers before it, The Mars Room shiftsbetween first and third-person narration.

The third-person sections, tellingly, focus on the novel’s rather unpleasant male characters: Romy’s client cum stalker Kurt Kennedy, ex-LAPD cop Doc and prison educator Gordon Hauser. Gordon, the least vile of the three, once started (but never finished) a master’s thesis on Henry David Thoreau.

When Gordon moves to a one-room cabin up the mountain from Stanville to live out his enthusiasm for Thoreau’s ideal of self-reliance, his friend Alex sends him a Ted Kaczynski reader as a joke. Chunks from the Unabomber’s actual diary punctuate the novel without further explanation, though we are clearly being prompted to consider freedom — its meaning and who or what prevents the individual from obtaining it — from a variety of angles.

Kushner faces two challenges to reader interest with this choice of material. The first is a challenge related to character: How to generate sympathy for a violent offender? The second is a challenge related to plot: Romy is serving multiple life sentences without the possibility of parole; her journey is over before the novel even begins.

As her seatmate Laura Lipp says on the bus to Stanville: “In prison you know what’s going to happen. I mean, you don’t actually know. It’s unpredictable. But in a boring way. It’s not like something tragic and awful can happen, since that’s already taken place.”

Kushner deals with these challenges in predictable and not-so-predictable ways. The plot is given an injection by a vulnerable seven-year-old son in the world outside as well as the rising tensions among the inmates with the imminent arrival of trans woman Serenity Smith at the prison.

As far as character is concerned, Romy is softened by a backstory: there is a disengaged mother and a violent stranger “who looked like someone’s father”.

Her no-nonsense honesty is also very likeable: “If you have never tried heroin I have news for you,” she confides to the reader early in the book. “It makes you feel good about yourself. It makes you feel good about other people. You want to give the whole world a break, a time-out, a tender regard.”

Shows like Orange is the New Black would have you believe that in prison people become more, rather than less, who they really are. But The Mars Room argues the exact opposite. A great achievement of the novel is the way it charts the disbanding of personality by the experiences of incarceration.

The “voiceyness” of Romy’s reminiscences of drug and risk-taking in 1980s San Francisco cedes to point-of-view narration that becomes increasingly animal. Romy is reduced to bare life and we are asked to note some similarity between her and the mountain lion that Gordon hears shrieking on his first nights in the cabin. As she tells us early in the novel, “The era of me, the phase of me, really, had ended.”

That the self is extinguished by prison means inmates are caught in a catch 22: the only hope they have of getting out of that place necessitates inner searching, which is no longer possible.

This is one of several lines of argument Kushner pursues against the American justice system in the novel.

She also exposes the distortions to the truth that the evidence law upholds and the bad faith involved in condemning a person to life in prison on the basis of a single act. The Mars Room is, ultimately, a critique of society’s habit of locking up the suffering for their suffering and making “poor people without reasonable options” their jailers.

Melinda Harvey is a lecturer in literary studies at Monash University and a judge of the Miles Franklin Literary Award.

The Mars Room

Rachel Kushner

Jonathan Cape, 340pp, $32.99

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout