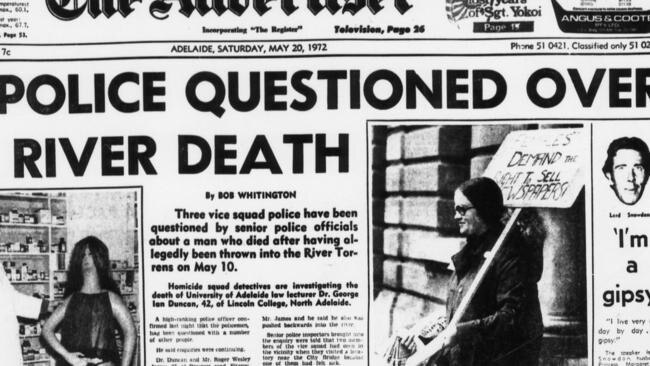

The killing of George Ian Duncan and the lingering trauma of gay hate crime

As Adelaide Festival director Neil Armfield unveils an oratorio about a notorious, unsolved killing, he reveals publicly, for the first time, that he, too, was the victim of a gay hate crime.

It was an ugly, unprovoked attack that led to pioneering gay rights reform. Yet 50 years on, the killing of Dr George Ian Ogilvie Duncan – a shy academic known as Ian to his friends and family – continues to haunt Adelaide.

Around 11pm on May 10, 1972, Duncan, a law lecturer who worked at the University of Adelaide, and another gay man, Roger James, were thrown into the Torrens River by a group of men they did not know. James broke his ankle during the ordeal but survived, while Duncan, who had only arrived in the city six weeks before, drowned.

Adelaide author and historian Tim Reeves writes that it was “a time when male homosexual acts were criminal throughout the country (and) the southern bank of the River Torrens in Adelaide was a beat’’ – a place where gay men went to meet up or have sex. Reeves, whose extensively-researched book, The Death of Dr Duncan, is being launched at next month’s Adelaide Writers’ Week, says the drowning of the 41-year-old academic “shocked the community with allegations that police, engaged in their regular activity of ‘poofter bashing’, were involved’’.

Despite a police investigation, coroner’s inquest, independent probe by New Scotland Yard, whistleblower allegations of a police cover-up and a manslaughter trial involving two ex-vice squad officers, no one has been convicted in relation to Duncan’s death.

Adelaide Festival co-artistic director Neil Armfield believes this unsolved killing still reverberates uncomfortably in the city of churches. The eminent theatre, opera and film director sighs deeply as he recalls how the Scotland Yard investigation concluded that three vice squad officers had taken part in the killing – yet characterised the crime as a “high-spirited frolic which went wrong’’. “Awful, awful,” is how Armfield describes that finding.

How does the festival boss – who, as a young man, had his nose broken in another unprovoked attack at a Sydney gay beat – feel about the fact no one has been brought to justice over Duncan’s drowning? “It’s an ongoing source of pain and anger,’’ he replies.

To mark the 50th anniversary of this notorious case, Armfield is directing a new oratorio about Duncan’s death. Titled Watershed, it’s said to be the most ambitious artistic response to date to the drowning. A co-production between the Adelaide and Feast festivals and State Opera South Australia, it will draw on inquest transcripts, media reports, Duncan’s private letters and historical photographs and features a “no punches pulled” libretto by high-profile writers Alana Valentine and Christos Tsiolkas.

Brisbane composer Joseph Twist, a winner of the Chanticleer Prize for international choral composition, has created the score, which will be animated by three soloists, the Adelaide Chamber Singers and a chamber orchestra.

Armfield, who has won two AFI and 12 Helpmann awards during his four-decade, international career as a film, theatre and opera director, opted to have Duncan’s story told as an oratorio, because this form sits “with the idea of commemorating religious events, and I think one can view the death of Duncan as a kind of martyrdom. Also, the sort of religious vibration around the central character allows for a secular oratorio. Duncan himself was a high church (Anglican) believer, or certainly enjoyed the theatre of it.’’

The 66-year-old festival director, who was in his final year of high school in Sydney when Duncan was killed, reflects how the lecturer drowned in an “iconic” Adelaide location: “That area of the Torrens is right there at the Festival Centre, it’s right there at Adelaide University, at Jolley’s Boathouse where we do so many of our donor functions. Every day in Adelaide you’re walking across the beautiful bridge that goes across the university. You’re walking the path of that crime, and so it does haunt Adelaide. The fact that it’s never been called for what it is and the alleged perpetrators … have never been proven to be guilty, creates an open wound.’’

According to Reeves, who is Watershed’s historical consultant, the case was reopened in 1985, following claims by ex-vice squad member Mick O’Shea of a police cover-up. Three police officers were subsequently charged with manslaughter. Two of them faced trial but were acquitted in 1988.

In 1972, ABC television quoted another Adelaide academic who said he had been attacked on the banks of the Torrens by men he alleged were vice squad members. “This sort of thing,” he claimed, “has been happening as long as I can remember.”

Armfield refers to allegations about South Australian police “teaching poofters to swim” by tossing them in the Torrens, noting that on the same evening Duncan drowned, “we think that three gay men were thrown in the river at least’’. “We call it a murder (but) obviously they (the perpetrators) weren’t trying to drown him,” Armfield says. When Duncan, tragically, did not re-emerge from the river, an off-duty police officer allegedly “stripped down to his underwear and dove in, attempting (unsuccessfully) to find the body”.

Watershed will explore how this deeply disturbing case sparked community outrage and led to world-first gay rights reform in South Australia. In 1975, the famously progressive Labor premier, Don Dunstan, championed legislation that made South Australia the first Australian state to fully decriminalise homosexual sex. In a statement, Reeves explains: “The 1975 legislation was also the first in the English-speaking world to eliminate any distinction in the criminal law between heterosexual and homosexual acts, including an equal age of consent.”

Dr George Ian Ogilvie Duncan – born in London, raised in Victoria and educated at Melbourne and Cambridge universities – lived a quiet, solitary life, yet his death became a turning point in the evolution of LGBTI rights.

One of the nation’s most accomplished directors, Neil Armfield has often made a point of separating his sexual identity from his work. “In some ways I’m a great believer that artists should be able to escape their own identity and sometimes I’m against fashion in that,” admits the man who has directed theatre and opera productions from Broadway to Covent Garden, and around this country.

However, with Watershed, he says it is “very important” to recognise how a “sense of very personal outrage on Duncan’s behalf is something gay people feel”. Armfield, too, has been a victim of a gay hate bashing and, for the first time, on these pages, he has decided to publicly share the full story of this attack and the “sneering” response of NSW Police.

On a Saturday night in May 1986, Armfield was driving home from a friend’s birthday party and stopped at a well-known gay beat in Moore Park, a large expanse of parkland on the outer edge of Sydney’s CBD. Then 31, Armfield had just arrived at the beat when “I just got grabbed by my collar from behind and swung around and straight into a king hit on my nose. My nose broke and there was a gush of blood. And as they hit me they yelled, ‘AIDS poofter’. There were about five guys (in their) mid-20s.”

In a stark reflection of the terror he felt, the director lost control of his bowels. “I knew that if I hit the ground I’d be gone because they’d lay into me and kick me. So I just fought to stay upright and I screamed from the bottom of my being, ‘Why are you doing this, why, why, just why?’ And all they could reply was ‘AIDS poofter’.” (At the time, the AIDS epidemic was killing many young, gay men and intravenous drug users in inner Sydney.)

The thugs demanded the director’s grey Swatch watch, which he handed over. They also demanded his wallet and he told them it was in his car. This was a shrewd tactic by Armfield to move into a better-lit space.

“I knew that I had to get away from this very dangerous, secluded place. One of them had picked up this big plank of wood … and if I’d been hit with that it would have been … curtains. I think they were a bit freaked by the blood and by the shit.”

As he and the attackers reached his car, which was parked on a main road, a passing driver stopped and shone his lights on them. Startled, the young men threw Armfield’s keys into the grass and ran away, while the good Samaritan asked if he was all right. “I said I was OK and thanked them.”

Armfield found the keys and drove home covered in blood with his busted nose, before “I burst into tears”. The following Monday, his close friend, prominent journalist and author David Marr, went with him to Taylor Square police station, located at the epicentre of Sydney’s gay nightlife, to report the assault. The police’s dismissive response to the attack is something the Adelaide Festival director has never forgotten.

Armfield was, even back then, one of the nation’s leading theatre artists – he had been appointed co-artistic director of Nimrod Theatre at the age of 24 – but neither this, nor his injuries earned him much respect from the cops. He recalls that they asked, “What were you doing in Moore Park?”. “And I said I wanted to go to the toilet … on the way home after a party. And they said, ‘We don’t think you were; you’re lying. You were there for sex.’ David said, ‘What does it matter?’ And they were horrible.’’

Armfield tells Review that “my point was that this (assault) happened at precisely the time people who were more unlucky than I was, were being killed … Those crimes were not being explored, not being investigated or linked together. I have such a vivid memory of the faces of those young men that I could have easily identified them, which is what I assumed would happen: I would be called back in, they would have pictures of people who were suspected of bashings or of murders.”

Instead, “I never heard a word back.”

Armfield first told this story during an early workshop for Watershed, and Valentine found it so powerful, she included it in a draft libretto. Armfield ultimately didn’t want the show to be about him, so he says matter-of-factly, “it didn’t survive to the second draft”. However, his personal experience of a gay hate crime the police did not take seriously “is certainly a real point of entry into the work for me”.

Asked about the assault’s psychological effects, he says that “in the short term I think a sense of shame … I didn’t tell my parents the circumstances of the bashing. I wasn’t honest about it.” At the police station, “I was made to feel like it was my fault and I sort of felt ashamed of the experience.” He also recalls that, for months after the assault, “if I was using an ATM and someone came up behind me, I would react very fearfully”. He also needed to have surgery to fix his deviated septum.

Soon after the attack, he started rehearsals for a production of the Louis Nowra play, The Golden Age, at NIDA, “and I remember my nose being all bandaged up”.

When colleagues asked him about his injury, “I suspect I just kept to the story that I’d given to my parents, that I was bashed in a back street near Oxford Street. As the decades have gone by, I have looked back on it and thought, ‘What’s the point? It’s actually been liberating to talk about it honestly’.”

Why break his silence so publicly now? While Watershed has been a catalyst, so has the realisation that “it could have been so much worse, and I know that for others it was so much worse. And you know … I’m a witness.”

The physical repercussions of the homophobic bashing linger, even now. Because his nose was broken, “when I went for one of my Covid tests they couldn’t get the applicator in the left side”. It also left him with a nasal-sounding voice, he says.

Attaining “justice is such a tangible experience,” Armfield reflects, noting how the killer of Scott Johnson recently confessed, 34 years after the gay American mathematician was murdered in Sydney. For years, police wrongly insisted Johnson’s death was a suicide. Armfield says the fact it was declared a hate crime before the killer eventually confessed “somehow gives you some air to breathe”. He pauses and reflects: “That has not happened with Duncan.”

In Watershed, South Australian opera singer Mark Oates will portray the enigmatic Duncan as well as the great reformer Dunstan, while bass vocalist Pelham Andrews will portray O ’Shea, other police officers and magistrates.

Ainsley Melham, who played the title role in the Australian and Broadway productions of Disney musical, Aladdin, will play “the lost boy’’, a fictional character who, according to Armfield, “represents the people who were murdered on the Torrens who weren’t George Ian Ogilvie Duncan, ordinary kids who’ve been bashed around the country. He provides a narrational voice as well.

“We know there was another drowning in the Torrens later that year in that area; a young man’s body was found in the river in October of that year. It goes on,” he says emphatically.

“Look at all these deaths in Sydney across the ’80s.” (Underscoring how timely Watershed is, the NSW government recently announced it would hold an inquiry into gay and transgender hate crimes that occurred between 1970 and 2010.)

Armfield says that while “there’s a very strong sense of Duncan’s personality” in the show, it won’t be a dramatised biography: “Part of the interesting thing about Duncan was that he was such an enigma and so closed to himself. He would never, as one of the songs says, have identified as a homosexual. So many people who go to beats don’t, and particularly at that time. He sort of internalised homophobia and fear, and attraction to the darkness, to the illicit.

“Christos, through his novel Loaded and the (spin-off) film Head On, has such a sense of the energy and power of the illicit. That’s really interesting to explore, because there’s a powerful sexual current and sexual life in that impulse. Atmospherically that’s very important, to get a sense of what the world is and what the attraction of the beat is.”

Co-librettists Valentine and Tsiolkas, will, he says, “paint a portrait of Adelaide and Australia at that time, but also look at what the reverberations (of the case) are. The idea is to tell the story as well as look at our world today and to look at the history of pain and triumph in the movement of gay law reform in this country.”

Armfield came of age in an era when homosexual sex was illegal in his home state of NSW (it was legalised there in 1984) and he says he “couldn’t have predicted” the sweeping gay rights reforms that have occurred since then.

Witnessing the positive effects of legalised same-sex marriage has changed his view about the importance of this institution to the LGBTI community. “I always regarded marriage as something that is a socially conservative institution for the patriarchy,” he jokes. “But since the passing of the equal marriage legislation in 2017, the change that has made across society in terms of releasing a sense of difference, and the internalised sense of difference, injustice and homophobia, has been extraordinary.”

He also says the Taylor Square police station has “transformed” in terms of its support for the gay community. He sees signs that Watershed is being staged at a time of reckoning over past gay hate crimes: “I feel it’s such an important work and I really want to try and frame it in a way that does justice to its power.”

As for the sobering reality that Duncan’s death remains unsolved after five decades, the director says: “You can only hope that when those guys (the perpetrators) have nothing left to lose – like the guy who murdered Scott Johnson – that they might come forward and just say, ‘We did it’.”

Watershed: The Death of Dr Duncan runs from March 2-8 at the Adelaide Festival.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout