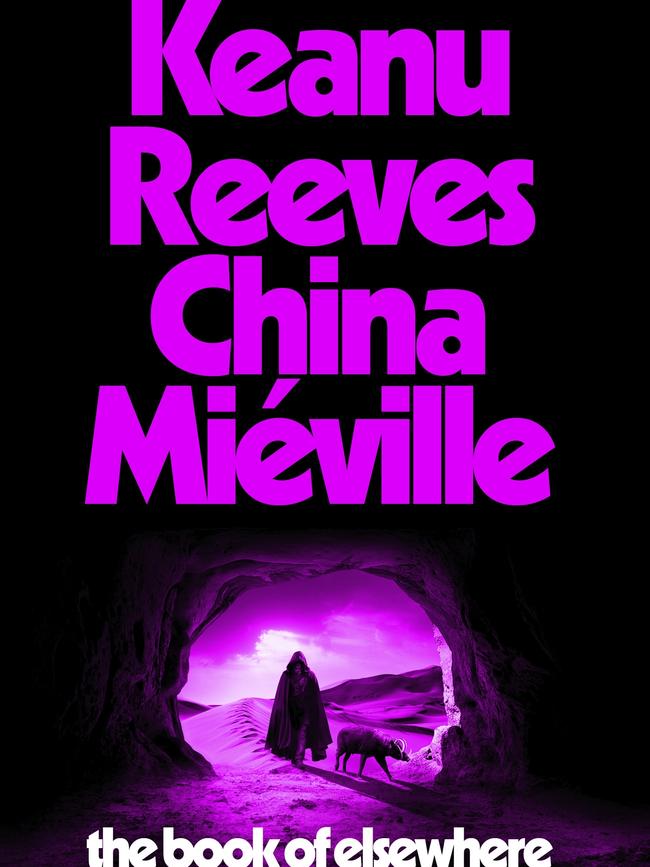

The hero of Keanu Reeves’ novel is 80,000 years old — which is how I felt by the end

We might have known that Keanu Reeves was harbouring literary ambitions as soon as he started saying words like ‘gestalt’ in interviews and publishing hand-stitched collections of poetry.

I am not sure that anyone watching the time-travel comedy Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure in 1989 would have pointed to Keanu Reeves and said: this goofy, guitar-bothering surfer dude will become one of the most beloved actors of his generation, and one of Time magazine’s most influential figures of the 21st century.

To that, can we now add: successful novelist?

We might have known that Reeves was harbouring literary ambitions as soon as he started saying words like “gestalt” in interviews and publishing hand-stitched collections of poetry (“I draw a hot sorrow bath/ in my despair room”, Ode to Happiness, 2011), although some would say the biggest clue came when the character he played, John Wick, killed a man with a hardback in a library. “I once saw him kill three men in a bar ... with a pencil, with a f***ing pencil,” one of his enemies says.

Looking back, all the signs were there that he was just itching to write a novel.

And now, here it is: Reeves, 59, has co-written a pulpy, genre-bending book with the much-garlanded sci-fi writer China Mieville. The Book of Elsewhere, an ultraviolent tale of an immortal warrior (“I kill ... I die ... I come back”) is crammed with fights and dismemberments, intestines and slaughter. It takes its lead from Reeves’s successful comic book series, BRZRKR, which started in 2021, with pictures of a moody hero with a “long fringe of black hair” who looks, well, suspiciously like Reeves. Expanded and novelised by Mieville, Reeves’s relentless gore-fest now has room not only for vowels but existential angst, mythological flourishes and long words such as “cachinnation” and “metaflora” and “haruspex”.

Our hero is the unkillable warrior Unute, who has lived for 80,000 years, “ancient when Gilgamesh was young”. He has killed mammoths with their own tusks, spent three lifetimes sitting on a rock on a mountainside waiting to see what will happen and has even performed in a pub production of Samuel Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape to an audience of 20 people, one of whom was the playwright. He wants to be able to die and has suffered all manner of pain and torn flesh. But he always respawns like a character in a computer game. Is he half god? Or some kind of alien? Perhaps Sigmund Freud, making a cameo (much as he does in Bill & Ted), has some answers.

The action is mostly set in a dystopian future where Unute has come to an uneasy deal with a US government black-ops team. If he can help them destroy a sinister evil force, the scientists will help him become mortal.

I mean, you have to say, that’s a terrific premise. What if instead of a mortal who longs to be immortal, the hero is an immortal who longs for death? The problem is that the authors’ “what ifs” get out of hand. What if the hero can be killed but then rehatches from an egg? What if the hero were also being chased through history by some similarly unkillable creature with a grudge? No sooner have Reeves and Mieville thought up this weird antagonist than we have the most surprising intrusion of a pig into a story since David Cameron’s premiership. “Nothing has ever hated me like that pig,” Unute says.

The novel has polyphonic urges too. In chapters with Chaucerian titles (The Servant’s Story, The Wife’s Story etc) we hear from secondary characters throughout history about how their lives have been disrupted by Unute. Unfortunately, Reeves and Mieville use the excuse of an 80,000-year-old time frame to overdose on “whences” and “thereafters”. It becomes exhausting trying to unpick sentences like: “If the unconscious is above all driven to avoid unpleasure, whence came such repeated goings-back to agonies?” While other sentences would make your ears bleed if you read them out loud: “Know you, said they, where walks a boar after he with whom once you walked?” And I’m not sure what a “vorago thowless and silent” is exactly. But if you’ve seen Reeves gamely scowling and monotoning his way through Kenneth Branagh’s 1993 film adaptation of Much Ado About Nothing, you’ll know the vibe.

The trouble spreads to the contemporary sections as well, which are bloated with jargon, inverted sentences and a pile-up of adjectives (“intimate allergic tenderness”). The prose is so purple it’s practically ultraviolet. Whole paragraphs are barely decipherable, with phrases such as “subliming off it with its own surplus quiddity”. How do you “sublime off” something? And what is “surplus quiddity”?

Overall, it reads as if Mieville has taken Reeves’s most colourful performances, fed the script into AI and produced a sort of hybrid language. Reevesian.

How else to explain sentences like this: “Even allowing for that, to those within, the noise wavered in and out of amplitude in stochastic stop-starts unrelated to the whirling of the rotors ...”

And talking of the whirling of rotors, there’s just so much action and noise for so little gratification. I lost track of all the many absurd reversals: “Vayn thought she was life and I was death. It was a lie!” OK, just wake me up when you’ve figured it out.

With so many things constantly and pointlessly happening, I felt like I’d been reading the novel for 80,000 years. This is not to deny its merits. I enjoyed the ideas. Mieville and Reeves are really grappling with something here — memory, immortality, death, pain, the whole sweep of human history. Some sections have real vigour and spirit and at times the scattershot sentences do quiver into eerie life. Suffice to say, however, that it’s likely to be far more compelling once millions of dollars of special effects have been thrown at it. The Hollywood star intends to play Unute in a live-action Netflix adaptation, while an anime series is in the works.

In the end one can only really stand in awe of Reeves, the 21st-century Renaissance man, determined to squeeze 80,000 years of activity into one mortal lifespan. You know he still plays bass in his band Dogstar? And just to warn you, he recently revealed his ambition to learn the cello.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout