The heinous truth about Carrolup Native Settlement laid bare

After almost half a century, a collection of Stolen Generation children’s art has finally been returned. Now we must confront the story behind it.

In April 1983 an Aboriginal man was murdered just north of Melbourne, bludgeoned to death with a car jack. His death would officially go unnoticed for 18 months, until Melbourne man John DeCarteret confessed the murder to police, directing them to the body nearby the town of Buxton.

Victorian media briefly reported the incident, describing the victim as a homeless Indigenous man named Ronald Revel Cooper. The brief article would make no mention of Cooper’s career as a prominent Indigenous artist: a prodigious child painter of the Stolen Generation, whose idiosyncratic works – equally resplendent with bold hues as haunted by portentous shadows – would be lauded both at home and internationally. It was merely a case of another dead Indigenous Australian.

Cooper’s life had ended in a tragedy befitting its painful beginning in the 1930s, robbed from his family and made a ward of the state at about six years of age under the auspice of the Aborigines Act of 1905. Cooper would be committed to the crudity of mission life in Western Australia, in the then-known Carrolup Native Settlement near the agricultural town of Katanning in WA’s Great Southern region.

Carrolup had initially been established in 1915 as a remote outpost in which to forcibly segregate Aboriginal people from the town’s white population, and furthermore exploit them as farm labourers and domestic servants. In 1939 the Department of Native Affairs repurposed the settlement for the housing of children for a by-now methodical practice of removing mixed-race children from Aboriginal families. WA’s then Chief Protector of Aborigines, A. O. Neville, was chillingly pertinacious in expounding the program’s mandate: to breed out black Australia and “to merge (mixed race Aboriginal people) into our white community and eventually forget there were any Aborigines in Australia …” The Bringing them Home report has since put the number of children removed Australia-wide between 1905 and 1967 as upward of 100,000.

Despite limited education and a termagant life, Revel Cooper wrote vividly of his time at Carrolup: a place delineated by its austerity, where the threats of physical violence and solitary confinement were unyielding. “We were locked in our respective dormitorys (sic) at 5pm winter and summer, with no drinking water,” he writes in a 1960 handwritten reflection of life in the camp. “(An) open sanitary buckett (sic) was placed in the centre of the floor, being afraid of the supernatural we were afraid to leave our beds at night.”

In the heart of Noongar country – a vast area taking in WA’s entire southwest, stretching from beyond Jurien Bay on the Indian Ocean to Bremer Bay on the Southern Ocean, and including the WA capital Perth – this land has known at least 45,000 years of Noongar habitation. Today the Carrolup settlement, later rebranded Marribank, rests almost tranquilly in picturesque ruin amid vibrant canola pasture and mottled wandoo trees, with little to distinguish it from other abandoned settlements that pockmark the state’s southwest.

But the unsettling shrill of the region’s rare black cockatoo augurs what lay beneath the gravel: the bones of countless children interred in unmarked graves. Adding to the already macabre, Carrolup was wedged between a leper colony and a mortuary. It is said that at night above the agonised moans of the leprosy inmates the children could hear the tormented cries of their families, camped beyond the fringes of the settlement in the desperate hope of reclaiming their daughters and sons.

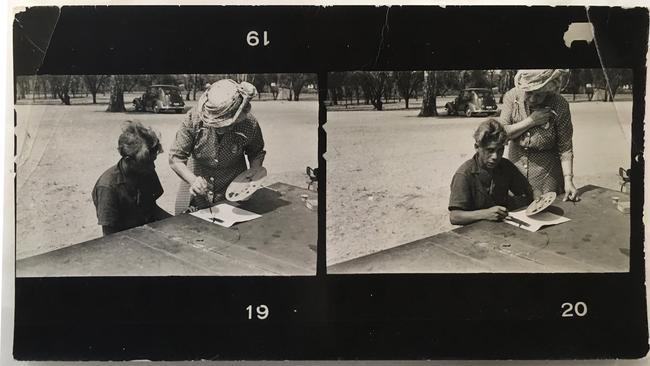

In 1946 newly appointed headmaster Noel White arrived at the settlement with his wife Lily and found himself appalled by the physical and mental condition of the children he would describe as “difficult to reach”. After a week the Whites resolved to resign their “hopeless” posting, until White encountered a young boy sketching trees on a paper scrap with discernible artistry. White offered the distrusting boy some coloured crayons and so would begin an art movement that would become known as the Aboriginal Child Artists of Carrolup: works now on permanent display for the first time in Australia in 70 years, at John Curtin Gallery in Perth.

“The children were prolific,” the Carrolup exhibition’s curator and Yindjibarndi woman Michelle Broun explains of the young artists aged 7-14. Broun appends that, beyond First Nations traditional creative practice, Carrolup was the first collective Aboriginal art movement in contemporary Australia: preceding Papunya by more than two decades. “(The children) used that as a tool to bridge cultures and create an understanding and find a common language. To find a way to communicate and tell their stories.”

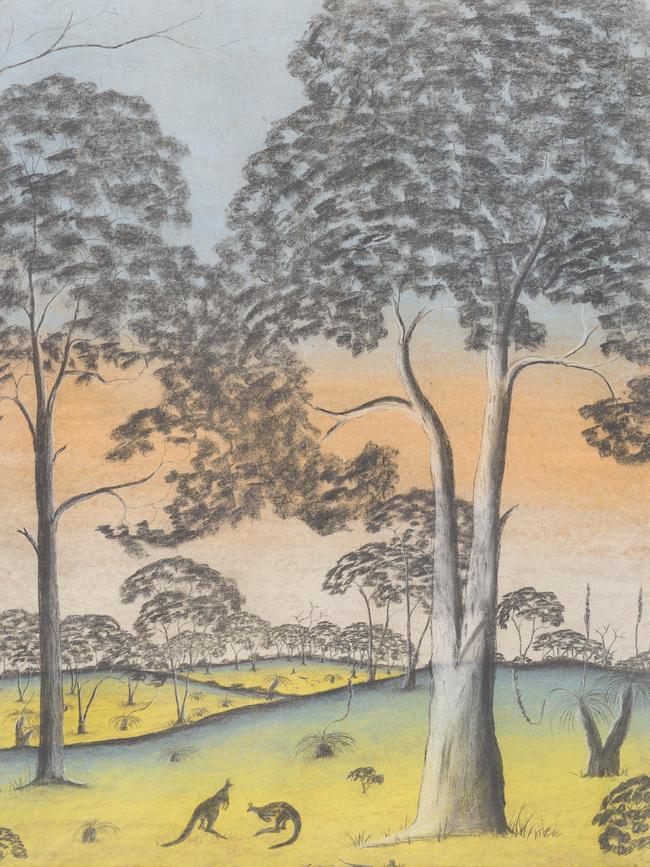

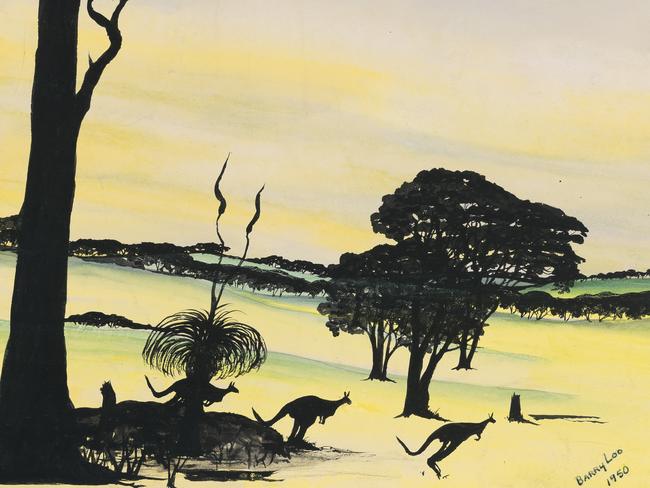

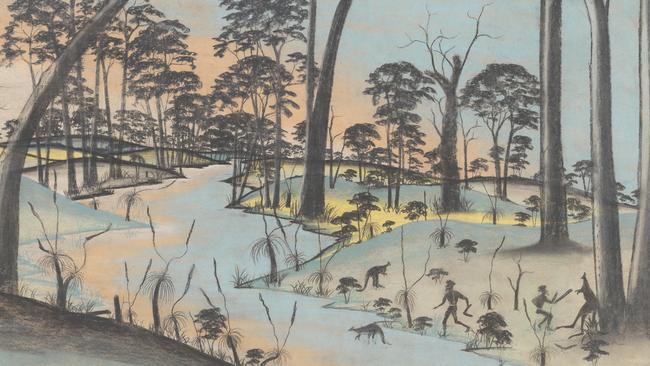

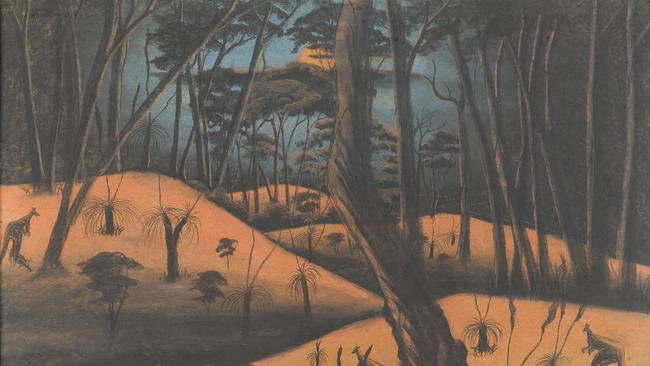

White would take the children on regular “rambles” through the surrounding bushland and encourage them to memorise the landscape for later sketching in their government issued notepads. This would manifest in highly accomplished figurative works with intricate landscape depictions of the towering salmon gum and scrubby wandoo, and enigmatic silhouettes of kangaroo packs on the horizon at dusk. Writer Dorothy Hewett would describe the works as “walking into the vigorous adventure of a child’s mind”.

The fate of the settlement, however, would be irrevocably transformed with the arrival of wealthy English philanthropist Florence Rutter in 1949, who was visiting her two sisters while planning to establish a Soroptimist chapter in Australia. On reading a local newspaper article on the children artists Rutter resolved to visit the settlement and found herself equally enamoured with the children as dismayed at their primitive conditions.

She found the wall of the main hall festooned in artworks using any shred of paper available. “Their animals and birds were so alive, their designs so unusual, and their colours so vivid – from such cheap crayons,” Rutter would later ruminate. “Their landscapes, too, showed such atmosphere, that the more I looked at them, the more astonished I became!” Rutter would purchase a number of works and exhibit them on her continued tour of Australia and New Zealand, forwarding on the proceeds to be used for the purchase of art supplies.

The children’s works were by now becoming increasingly more cogent and deeply metaphysical, with portrayals of traditional Aboriginal cultural practice, including a sacred corroboree. Otherwise vibrant and playful motifs suddenly seemed haunted with the spectre of a lone Aboriginal figure watching on in the far distance, and a serpentine road seemingly disappears away from the darkened settlement towards the soft light of home country beyond, where the children were never to return.

Rutter would travel to the UK with many hundred Carrolup artworks (some put the estimate as high as 600), where she would exhibit and sell them to collectors in London, Liverpool, Manchester, Edinburgh and Glasgow. The Carrolup patron would also co-author a book with Mary Durack, Child Artists of the Australian Bush, garnering significant global attention for the art movement as well as the heinous conditions under which the Stolen Generation works were created. So moved was Queen Mary she would have a letter of appreciation sent to the Whites expressing her fondness for two particular works by Revel Cooper, which she likened to “Chinese drawings” before proclaiming a “deep concern for the welfare of the Aboriginal children”.

Amid its rising international profile, the Carrolup Native Settlement would be inexplicably shuttered by authorities in 1951, something Kathleen Toomath – manager of the Carrolup collection at John Curtin Gallery, and daughter of its longest surviving artist Alma Toomath (nee Cuttabutt) – cites as “suspicious”. The children would either be moved on to other remote settlements or cast out into a world that was still well over a decade away from recognising them as Australian citizens.

Rutter, too, would abruptly find herself on hard times, rendered destitute after being swindled of her fortune by an imposturous lover and forced to sell her remaining 122 Carrolup artworks to US media mogul Herbert Mayer, before soon-after dying. In 1966 Mayer would donate his entire art collection to his alma mater, Colgate University in New York, where they would remain in absolute obscurity until the boxes were rediscovered by ANU Professor Howard Morphy in 2004. The works would be transferred to WA’s Curtin University in Noongar country in 2013, where they have since been undergoing cataloguing and restoration.

Entitled Carrolup Coolingah Wirn (the Spirit of Carrolup Children), the current exhibition sees the selected works on permanent display for the first time in seven decades: a precursor to the Carrolup Centre for Truth-Telling which is slated for opening at Curtin University in 2023: what will be the artworks’ permanent home. “These works are not just landscapes,” Noongar elder Ezzard Flowers – part of the Carrolup repatriation delegation to New York in 2013 – offers, deeply moved at seeing the works on display, “they are our stories.”

To date less than half of the 122 works in the Herbert Mayer collection have been formally attributed to artists including Cooper, Parnell Dempster, Barry Loo and Reynold Hart – artists also featured in collections at the State Library of WA and Berndt Museum. All of these artists would continue their creative practice into adulthood, although too often shadowed by tragedy. Within a year of Carrolup closing, Cooper would be charged with manslaughter and sent to the notorious Fremantle Prison for four years. He would spend much of his itinerant life rebounding in and out of penitentiaries across Australia, amid periods of great productivity. Under the patronage of Victorian collector and gallerist James Davidson, Cooper’s profile increasingly grew throughout the 1960s and ’70s, with recurrent comparisons to Albert Namatjira.

But alcoholism and dogged cycles of incarceration would ultimately sabotage Cooper’s ambition. While serving another prison sentence in Victoria in 1968 he would write lucidly of a lifetime of brutal racism and subjugation: “I was not born with an inferiority complex. I did not acquire one. I had one forced on me, and was made (by law) to accept this complex as my just lot.” Cooper would be murdered aged 49.

Herself a descendant of the Stolen Generation, Broun says it is too simple to write these tragedies off as abstracted history, and cites the recent discoveries of children’s graves in Canada and the abduction of Nigerian schoolchildren as examples of significant moments of global reckoning at systemic child peonage. Equally, the Carrolup collection remains incomplete, with many hundreds of artworks still believed to reside in private collections across the UK, as well as institutions such as the British Museum.

In late 2022 a number of Carrolup works will leave Curtin University to tour the UK, retracing Florence Rutter’s own footsteps in the hope of discovering and documenting further works and repatriating those home to their koort boodja, or heartland.

“This story is not finished,” Broun concludes. “I can only speculate, but I think these children would have preferred to be home with their families on country rather than locked up in a dormitory or in solitary confinement. But these artworks now exist, and we must honour that. Where there is trauma there is also hope.”

Carrolup Coolingah Wirn (the Spirit of Carrolup Children) is showing at WA’s John Curtin Gallery until late 2023.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout