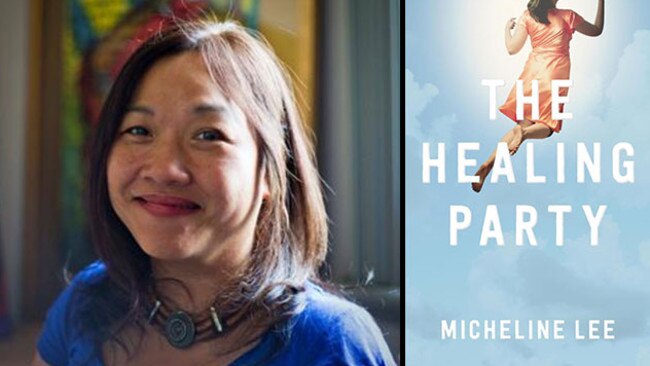

The Healing Party, Micheline Lee: struggling with a leap of faith

Micheline Lee’s The Healing Party arrays the possibility of religious belief against the form that refuses it.

We know the novel to be an incorrigibly secular form. If religion, at least in its Christian, western European guise, is concerned with one book, one God, one unassailable set of truths about this world and worlds to come, then novels are plural, relative, concerned not with singular truth but with millions of competing certainties.

Which means novels about religion are uneasy hybrids. They either employ spiritual cadences to secular ends, or else work like anthropologists, focused on those who do experience religious belief as though they were members of a forgotten tribe.

What the novel can do, however — and Micheline Lee’s droll, angry and intensely felt debut The Healing Party does it with flair — is to array the possibility of belief against the form that refuses it. Her novel is a tool for registering perplexity in the face of tragedy, loss and the general impoverishment that attends our profane state. She shows us that the one thing a form founded on doubt may not do is exclude the possibility that others’ convictions are real.

The sceptic in this case is Natasha Chan, the 20-something daughter of Chinese migrants washed up in Melbourne after expatriate years in London and a middle-class life in Hong Kong. Natasha hasn’t lived at home for years. When her older sister Anita calls to report that their mother has terminal cancer, she is leading a modestly happy existence in Darwin with a worthwhile job and a decent boyfriend.

There is an entire class of fictions that open by circling of the cul-de-sac of an individual life’s end. Many fail to negotiate the emotional complexity demanded by that narrative decision, but not this one. Natasha’s first lines of dialogue with her sister are the pencil sketch of a tough-minded, intelligent, instinctively adversarial woman. And yet her final response to the news has a little girl’s plaintiveness: “I want to come home.”

Back in Melbourne, in the family home that smells of soy sauce and brushed carpet, with gaudily painted walls and household shrines, the intervening years collapse. Natasha is reacquainted with a deep love and admiration for her mother, though these feelings are not obviously reciprocated. The once-beautiful, now wasted and wheelchair-bound Irene adores her husband to the point of excluding her four daughters from emotional intimacy.

Meanwhile, Natasha’s father Paul, an artist and photographer, has adored every attractive woman who has crossed his path. Until, that is, he found God and made sure the rest of the family did as well.

And in keeping with Paul Chan’s outsized personality, this is no garden-variety conversion. He finds Jesus in the Charismatic wing of the Catholic Church. Satan is a very real presence here, though God himself is often on the party line to help resist the blandishments of evil. Indeed his is a sect of vigorous spiritual spectacle: songs, prayers, laying on of hands, speaking in tongues.

It was Natasha’s unwillingness to accept this religious turn in her domestic life that lay in part behind her initial decision to leave home. She was and remains the family unbeliever. Now, having moved back into her childhood bedroom, Natasha sees an opportunity to soothe those old tensions. With energetic goodwill, she sets about nursing her mother and serving as helpmate to her father. She joins in the family prayer and the singing, lacing herself into the corsetry of faith.

What is unexpected, however, is how much comedy can be wrung from such a sad and sincere situation. This is where Lee makes magnificent use of Natasha, who operates at all times as the locus of narrative perspective, even as she sees herself as a minor filial satellite orbiting two gas giants. The young woman notes everything with an attentiveness that manages to be disdainful and reverent at once:

I leant my backpack against the carved mustard-coloured treasure chest that had travelled with us from Hong Kong. Taking up the wall behind the chest was dad’s photomontage of the Rapture. Visitors always commented on this work. He had collaged together portraits of nearly a hundred people, including our family, in a swirling mass of humanity flying heavenwards. But it was the ones who were left behind on the earthly battleground to whom the eyes were drawn. Partaking in every earthly vice, their faces were contorted in gluttony, rage, and loathing.

When Paul Chan announces that God has spoken to him and that he will have a healing party at the family home, during which a co-religionist’s vision will be realised and Irene healed of cancer, we know we’re headed for a showdown. Natasha’s buried reservations about the efficacy of her family’s faith and the rigid certitudes they insist on will be tested: one side will be proved right. And yet the resulting drama is richer and more complex than that.

Natasha has not weighed the degree to which belief has helped her father battle with his ordinary demons. She has not factored how much religion has salved the wounds opened up for her mother and sisters by earthly disease. The comedy of culture these pages describe can be uproarious and cringeworthy, as Paul Chan pulls out all the stops to ensure that his wife is granted maximum purchase on grace. But that foolishness can obscure the simplicities that underlie human action. Paul may be a baroque clown, but he is also a grieving man; and it is Natasha’s agnosticism that obscures such knowledge until it is too late.

Likewise, the novel as a whole. The Healing Party is an entertaining narrative that hides a large heart until its conclusion. It is a critique of religion that reserves its most powerful lines for those on the wrong side of the argument. Still, if there is a central faith here, it belongs to the elegantly elucidated confusions at which the novel excels. Lee honours those prerogatives with wit, maturity and unexpected skill. Her novel answers the question the renegade Jungian Robert Hillman asked back in 1983: “What does the soul want?” It wants fictions that heal.

Geordie Williamson is a publisher, writer and critic.

The Healing Party

By Micheline Lee

Black Inc, 296pp, $29.95