The enduring brilliance of Les Murray

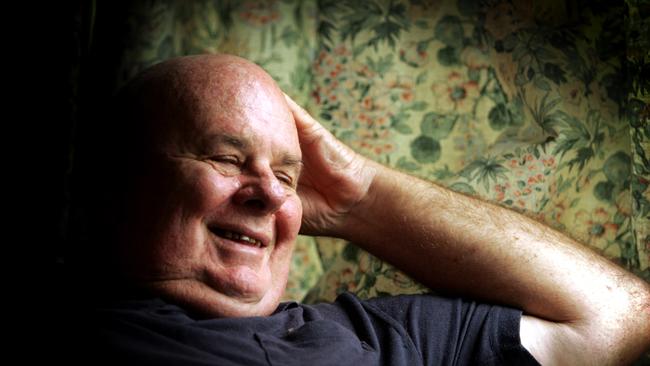

For the moment, Les Murray is still with us, still that same sprawling, shambling, magnificent man of Australian letters — not yet passed into the slipstream of memory. But there’s no telling how he’ll be remembered in a century’s time.

Les Murray has been gone five years now, and there’s no telling how he’ll be remembered in a century’s time. When he died, he left behind a hole the size of a planet, an enormous cultural void. That’s a big loss, impossible to measure. Like a mighty tree felled in an ancient forest or a towering monument cut down from its plinth.

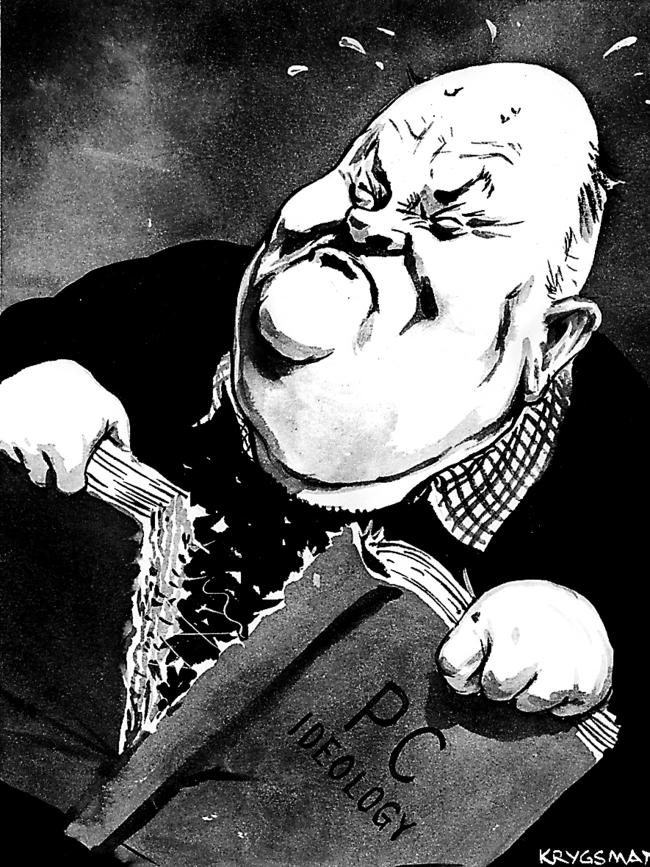

Last week, in these pages, The Australian’s chief literary critic Geordie Williamson described big Les as our “greatest poet” in an important essay on the appointment of our second Poet Laureate. You won’t find any dispute with that claim here. But legacy is a cruel and fickle mistress, always coveted but never guaranteed: what one generation considers worthy of posterity can just as easily end up on the scrap heap a generation or two later.

Plenty of distinguished poets have gone this way, whole armies of them, in fact; their life’s work thrust into a vicious cycle of boom and bust, only to be spat out the other end into a world that no longer recognises them. My hope is this never happens to Les Murray. His world – the world he brought forward in his poetry – is too vast, too varied, too brilliant to be left to the vicissitudes of contemporary taste and fashion. His influence can’t be weighed against the stiff ledger of market forces. That would be a true tragedy.

I never met Les Murray, and I’m envious of my friends and colleagues who did. I first encountered him in my early 20s, not through a collection of poems, but in an old episode of Desert Island Discs, recorded towards the end of the last century, then remastered and repackaged for the digital age. It’s the best interview I’ve ever heard, the most compelling introduction to this humble genius you could ever hope for. No one should miss it.

That experience fired a lifelong obsession with Les’s poetry, starting with The Ilex Tree and The Weatherboard Cathedral, then moving through to his later poems, Taller When Prone, Waiting for the Past and On Bunyah. (I keep his final set of Collected Poems, a weighty 700-page tome, at my bedside and consult it most nights.)

An old school teacher of mine, who knew Les in a past life, once interviewed him on Canberra radio and later recounted the experience in a book, not long after the poet’s death. He asked Les to recite An Absolutely Ordinary Rainbow. Afterwards he heard that people had stopped their cars to listen, just as in the poem.

When the interview was over they headed for lunch along a fashionable city street, lined with high-end cafes and restaurants. Les made a beeline for a fish ’n’ chips joint and ordered a roast-beef roll, lathered in thick gravy and salt. As the poet yarned over his meal, it dribbled down his chin and onto his shirt, but he didn’t care. His companion later recalled: “Here was a man who had created some of the most elegant poetry I knew … his work was as fine as gossamer. It’s just that his lunch wasn’t.”

In the days and weeks after his death, many eloquent tributes were written about Les, praising the strength of his poetic powers.

At the time there were no reports of how the old poet died, no precise details of what he was doing when he took his final breath. Still, I like to imagine him hard at work, seated behind a big wooden desk and a busted old typewriter with missing keys, adding the finishing touches to another masterpiece, shortly before hauling himself up and exiting stage left into a surfeit of light and colour.

For the moment, Les Murray is still safely with us, still that same sprawling, shambling, smiling, magnificent man of Australian letters, not yet passed into the slipstream of memory. He’s the poet whose shape everybody remembers, and the man whose verse is too good to forget. Along with his precious words, he’s also gifted us one important lesson: that genius can come from the most unlikely of places. Now surely that’s a legacy worth preserving.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout