The cult of Cathy Freeman, the indigenous girl who beat the world

In a singular sporting moment, Cathy Freeman’s story became the symbol of a much larger struggle for equality.

FREEMAN is a beguiling cinematic biography of athlete Cathy Freeman’s win in the 400m at the Sydney 2000 Olympics.

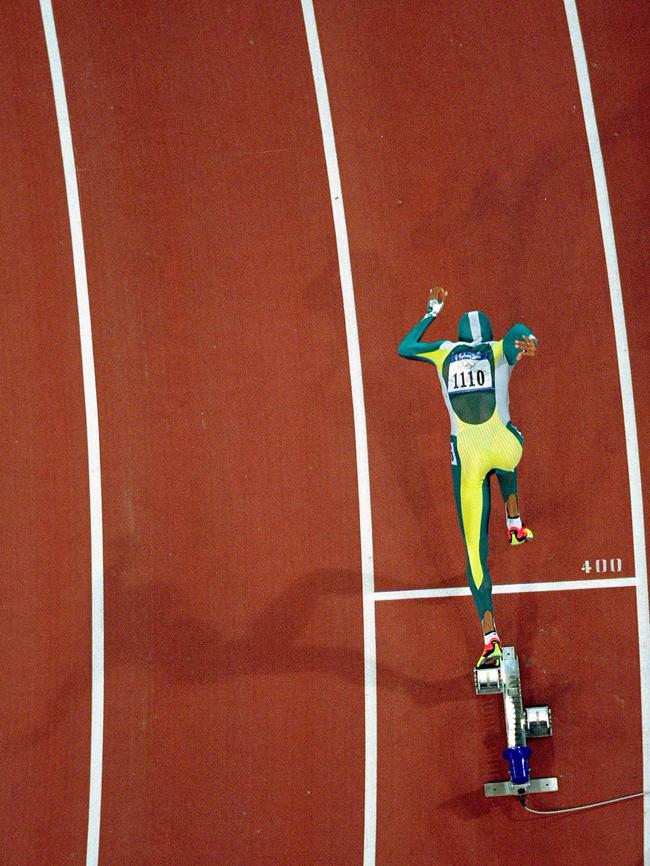

The race remains the most watched sporting event in Australia’s TV history, an extraordinary collective experience that had around 8.78 million viewers glued to Channel 7 as she strode out in that space-age stealth suit. And around the world people cheered as the young Murri woman from Mackay triumphantly carried both the Australian and Aboriginal flags in celebration.

The hour-long documentary comes from experienced French-Australian director, producer and writer Laurence Billiet, a cross media specialist whose company, General Strike (co-producer of Freeman with Matchbox Pictures) operates at the borders between screen, art and events. Billet has created many TV shows for companies as diverse as Lonely Planet television, US platform Hulu, National Geographic, National Geographic, Discovery, SBS and Eurosport.

Her collaborators in Freeman include director Stephen Page and his Bangarra Dance Theatre, and Helen Pankhurst from Matchbox, legendary producer of shows as diverse as Stateless, Old School and First Australians.

Twenty years on, Freeman – in her distinctive, self-deprecating fashion – explores the sheer singularity of this moment, its almost transcendent beauty and the way this slight young athlete found a connection to the whole country.

It’s a documentary in a form that’s much more experimental than the customary sporting film we see on TV – the usual talking head, cut away to action, voice over, back to talking head docos that simply illustrate a thesis. Or dramatically give the illusion of disclosure, conveyed by eyeball-crushing graphics, loud library pop music and one-second cuts. But Freeman, for all its cinematic singularity, is never pretentious, overtly polemical or accusatory. Instead it is seductive, sensuous and poetic, carrying a message but a creative artefact in its own right.

Billiet tells her story through character rather than facts, immersing us in Freeman’s narrative, seeking complexities and contradictions in unusual cinematic ways, photographed by award-winning cinematographer Bonnie Elliot, whose work on the recent Cate Blanchett series Stateless was visually stunning.

Together with her skilled collaborators, this inventive director has found a way to reflect on an event that brought us closer together in a time, two decades later, when the world is more open, complex, more confusing and more fragmented. “I felt a renewed urgency to tell this story that is a poignant reminder to people of the joys of social connection and people power,” Billiet says. “So much has happened since that night in September 2000 but there’s still so much to be done.”

Drawing on archival footage, interviews with prominent commentators, former athletes, Freeman’s family and a series of intimate conversations with Freeman herself – which act as a kind of subjective, almost dreamy narration – the film takes us on a journey through her remarkable sporting career and the frantic, at times hysterical, build-up to September 2000.

“It’s like looking through a mirror and what’s on the other side of that glass you can see the beast, and that’s the media, and that’s the noise, and it’s all the excitement and pressure from others; the intensity of it all,” Freeman muses in recollection.

“I consider it a beast because it can either eat you alive or, if you give it respect and acknowledge it, you can actually get on quite well with it.”

Freeman’s biography mirrors the rise of a people’s movement supporting reconciliation — her story became the symbol of a much larger struggle for equality — and Billiet winds in archival footage of the first National Sorry Day in 1998. By then Freeman was the first woman to win both the 200 and 400 metres at the Commonwealth Games, gaining extra notoriety when she carried the Aboriginal flag along with the Australian in defiance of the old white men who ran athletics in this country.

Freeman’s success and her often humorous militancy began to focus attention on the indigenous movement for equality, smashing negative stereotypes. “I think there were a lot of Australians who had grown up not understanding what had gone on with the Aboriginal people,” sports journalist Scott Gullen says, noting the way her fame focused attention on her people.

Everything in her life was difficult from an early age except running; she felt she could never be on an equal footing with white people until she raced, and then “it just changed”. As she became famous, the world champion, the narrative altered and indigenous people began to be seen in a new light and Freeman became determined to draw attention to the hardships her people had faced for centuries. “I wanted to shout – ‘look at me, I’m black and I’m the best’,” she says. “There is no more shame.”

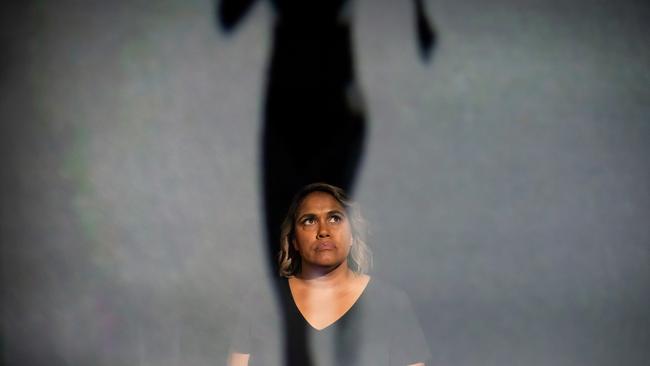

Her thoughts, ruminations and reflections are shared throughout the film as she wanders through an installation of floating gauzes, encasing a series of tableaux of projected images of her indigenous relatives. There’s an image of paternal great grandfather Frank Fisher, who served in World War One in the famous Light Horse Regiment. He arrived home to discover his military service was not recognised and he was not entitled to land grants given to white soldiers. And her maternal great grandfather, George Sibley, who refused to give over control of his pay to the police, his legal right, and was banished with his family to the penal colony of Palm Island. It’s an inspired device, as are the performances from Lillian Banks of Bangarra Dance Theatre, choreographed by Stephen Page, which create an emotionally charged insight into Freeman’s spirit at different times in her journey to greatness. Banks demonstrates her moments of preparation, her complete vulnerability and anticipation, even what the athlete describes as the electricity at the end of her fingertips running to her head, down to her neck and to the tips of her toes. And what Freeman calls “the otherworldliness of it all”.

It’s a documentary celebrating not only one of our greatest athletes and the way she was at the centre of one of our proudest sporting moments but how with some delight she unwittingly played a role in determining our national identity. She epitomises the power of dreams, the young indigenous woman who beat the greatest.

And there had been shame as this lovely film reveals. “I was a kid who was quite embarrassed to be a black kid; I sort of grew up with that self-image,” she says. “I could never understand that whenever I smiled at someone they never smiled back; I used to get really upset, why don’t they smile back at me?”

The country not only rallied around an indigenous female athlete, who delivered when it mattered on the greatest stage on the earth, but began to understand that the pernicious narrative of how indigenous people were seen was changing as she drew attention to the history of oppression her people had suffered for centuries. Her racing, she says, was propelled by her ancestors, “the first to walk on this island”. And did it with grace, charm and that mischievous chuckle that she could never hold back, even when shaking hands with prime ministers.

And she laughs frequently through this film.

There’s a lovely moment just before the start that Billiet covers in delightful tight close-ups of Freeman, cutting slowly from one to another as she remembers how she felt.

“I instinctively take some deep breaths, in and out, looking up to the sky; it’s so I don’t feel suffocated by this moment and I’ll breathe to the heavens as if to say ‘help me’,” she says, as if she somehow saw the universe and all its workings. And then she laughs and giggles and guffaws.

And the race itself is beautifully cut by editor Daniel Wieckmann, poetically suggesting the sense of flight so obvious in watching Freeman run and what she calls “the sheer bliss” of racing.

The moments at the end of the race are kept silent as Freeman collapses and takes off her shoes to feel the earth beneath the track. “Everyone was at one together,” she says. “It was as if we were the only people that existed in the world.”

Freeman, Sunday, ABC, 7.40pm.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout