The Cross: meaning through the millennia

The piece of wood on which Jesus was crucified has become a mark of condemnation and salvation.

This is a book about the fecund life of a symbol. When the Romans thrust a cross into the ground in their Judaean province and hoisted a Galilean troublemaker, Jesus, on high, they set off a gush of metaphors and analogies. The implications, the connections of Jesus’ form of death were teased out and the result has contributed much to that aesthetic richness that is one of the glories of Christianity.

The writers of the Gospels seized the opportunity at once. “When I am lifted up from the earth,” St John records Jesus as saying, “I shall draw all men to myself.” To die in an elevated position with arms outstretched was far more potent than to be beheaded or hanged or burned or poisoned.

What most set off the disciples and theologians and imaginative artists (and they were frequently the same person) was the material from which the cross was made: wood, part of a tree. How suitable it was, the commentators said, that when the first man, Adam, had sinned and lost paradise it had been because of a tree.

But now the bridge back to paradise had been restored and humanity saved from the consequences of sin by another representative man’s embrace of a tree.

In a wonderfully pleasing, satisfying way the elaborations went much further. The cross had in fact been hewn from Adam’s tree. The tree, as well as humankind, had been redeemed.

Then, as John Donne memorialised it, “We thinke that Paradise and Calvarie, / Christ’s Crosse, and Adam’s Tree, stood in one place.”

So ancient tradition had it that Golgotha, meaning the place of the skull, was the site of Adam’s grave as well as his sin. Hence many artists’ renditions of the crucifixion show a skull at the base of Christ’s cross. All human beings die because of Adam, all are reborn because of Christ.

On and on the elaborations have gone: the cross is the ultimate “tree that springeth green” for its fruit has been brought back to life. “The fruit of that forbidden tree … brought death into the world, and all our woe,” as Milton had it, but the fruit of the tree of the cross brought back life.

Not only was Christ’s cross an instrument that stretched back to the beginning of the human story, it was signalled and recalled everywhere in the present. Early Christian commentators saw it in ships’ masts, legionaries’ banners, farmers’ ploughs, even in the human form itself.

This irrepressible inventiveness of the cross extended to the original’s (or at least the putative original’s) own material reality. Rediscovered and unearthed in AD324 by Helena, the mother of Constantine, it became a veritable cut-and-come-again cross; Paulinus of Nola actually argued that the cross, although constantly divided, suffered no diminution. (Despite that, priests in the sixth century were worried about Jerusalem pilgrims kissing the cross and trying to bite off and secrete slivers of the wood in their mouth.)

Naturally legends and apocrypha blossomed well beyond the confines of the Gospels.

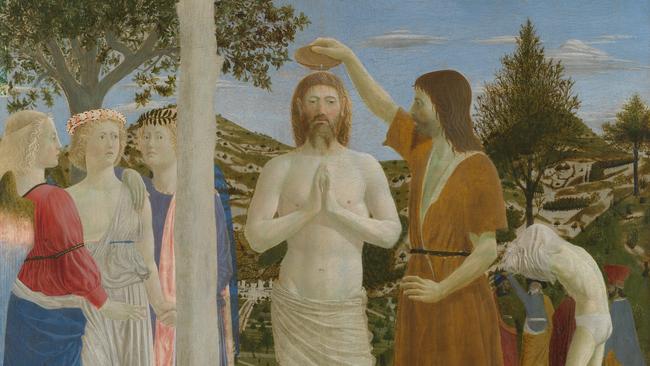

An individual scene in Piero della Francesca’s great cycle in Arezzo, Italy, The Legend of the True Cross,illustrates one such story. Far in the background of the tableau depicting the death of Adam is someone talking to an angel. Adam had sent his son Seth to the gates of paradise to ask for just a twig from the tree of life whose balm might ease his suffering.

But Seth is stopped by the archangel Michael, who says the day has not yet come when the tree of life will be once again available to humanity.

Robin M. Jensen, professor of theology at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, surges through the millennia sweeping up characteristics and oddities of the cross. She notes significant changes in its style and meaning.

For the first few Christian centuries crosses had no figure on them. When one was allowed, Jesus and his cross were statements of triumph, asserting that death had died.

But by the end of the Middle Ages the emphasis had changed to a suffering Christ. The point of the cross now was to move the faithful to feel what Jesus had gone through for them. The anguished and contorted figures of Spanish crucifixes must be the classic case. (In a section relevant to the other book reviewed here today, there’s a discussion of the cross and the Protestant Reformation that opens with Martin Luther’s artistic ally Lucas Cranach the Elder).

The major curiosity of this easy-to-read book, from the most academic of all publishers, Harvard University Press, is its complete lack of any intellectual argument. It strews meanings and examples prodigally, but its author remains utterly po-faced when you’d expect some argument or at least discussion.

Surely she could have said something about the unique phenomenon of a religion having an utterly negative symbol as its defining badge? Or about a historically verifiable criminal being acclaimed as God? Couldn’t Jensen have gone a little bit further, in other words, than merely pointing out some semantic paradoxes?

Not easy questions certainly. Less confronting ones, however, that she actually adverts to, she is just as ready to slide around. An early historical issue and a modern ideological one illustrate the point. Jensen simply makes no comment at all about the authenticity of the story of Helena finding the true cross. She gives us multiple variants but eschews any trace of a summing-up argument.

Then, in her final pages, she reports that feminist theologians “have argued that the image of the crucifixion has been used as a justification for abuse and even violence against women and marginalised people”. There, if anywhere, a reader might expect a bit of fleshing out of the position and some considered reflections on it. But not a peep. Such reticence does nothing to suggest that theology is an intellectually robust discipline.

Gerard Windsor’s new book is The Tempest-Tossed Church: Being a Catholic Today.

The Cross: History, Art, and Controversy

By Robin M. Jensen

The Belknap Press, 280pp, $35 (HB)