The Church frontman Steve Kilbey reveals his battle with heroin

IN this edited extract from Talking Smack, the Church frontman Steve Kilbey opens up about how an 11-year heroin addiction changed his life.

AT the age of 37, Steve Kilbey found himself at a crossroads. He’d become a pop star fronting the Church, a band whose song Under the Milky Way, the lead single from their fifth album, Starfish, became a worldwide hit in 1988. He’d made quite a lot of money: he had a house and a recording studio in Sydney, a couple of cars, a load of instruments and some cash to spare. He wasn’t filthy rich, but he was certainly very comfortable.

By this point, Kilbey considered himself a worldly drug user: he had started smoking pot in his late teens, tried psychedelics soon after and bought his first gram of cocaine after making his first record, Of Skins and Heart, in 1980. Eleven years later, he was recording for a new project named Jack Frost with his friend Grant McLennan, a fellow Australian pop star best known for his work with Brisbane act the Go-Betweens. One night, while out at a bar and feeling an empty sense of unhappiness at the life he’d earned, despite his success, Kilbey was taken aback by McLennan’s proposal: “Let’s get some heroin.”

“It came right out of the blue,” Kilbey recalls in February 2013. ‘It was the last thing on my mind. I went, ‘Oh, here’s $100, get me some too.’ No one had ever offered it to me up until then. All the other drugs you might get offered, but no one ever says, ‘Hey, want some heroin?’ It’s not like that. If you’ve got a stash, you don’t offer it. You don’t really go around turning other people on. It’s not the sort of thing you advertise.’”

When McLennan made his proposal, Kilbey thought to himself, Yeah! That’ll shift things around a bit. “As a teenager, I’d been hearing how bad marijuana was; people were being arrested and chucked in jail (for using it). And then, when I started smoking it,” he says, “I thought it was the most benign, pleasant thing that doesn’t seem to have any real drawbacks. I wrongly assumed heroin might be the same. I thought it might be the victim of really bad press, and that all the perils had been exaggerated.” He pauses for a moment, then laughs.

“And I believed that for a little while, naively.” He had no idea that his first taste of that substance would come to define the next 11 years of his life.

“I loved it. The moment the f..king stuff hit my nostrils, I was like, ‘Wow, this is what I’m looking for,”’ he says. “All my life, I’d had my conscience going, ‘You’re a horrible guy, you don’t deserve what you’ve got. You did this and that, and your mum and dad didn’t love you.’ All this stuff. And then, the moment that first line of heroin hit my nose, it all stopped. I was sitting there going, ‘Oh, I’m all right. I feel kind of cool. I feel like people could like me.’

“It stopped that whole dialogue instantly, and I felt warm and cosy and happy.”

He acknowledges that not all heroin dabblers experience this instant affinity for the drug; some try it and think it’s horrible.

“But for me,” he says, “it was like” — he snaps his fingers — “something I’d been waiting for my whole life.”

The wealthy pop star saw no reason to hide his fondness for this drug from anyone. Around this time, some “bad characters” started hanging around a house in Surry Hills that Kilbey had rented, which doubled as a recording studio. “Some of them were heroin addicts,” he says. “They were buying heroin for me. Eventually, I met some dealers. I was off and running.”

One of those characters was a doctor who had been deregistered due to her addiction. She beckoned him over, found a vein on the back of his hand and injected him.

“For a while, it seemed to me like, ‘Wow, how good is this? I’ve got a doctor very carefully doing all the right things, talking to me about my veins and my arteries, finding different veins and showing me how to do it. This is really legit,’ ” he says. “So I learnt how to shoot up. Bang. I was off, and on the downward spiral.”

It wasn’t just the drug and the process of injecting it that gripped him.

“I was interested in all of this bullshit: who was in rehab; who was in jail; who was selling; stories of the great heroin of the past, from Thailand or wherever. It was all I lived and breathed, this rubbish world.”

He defines that year of his life, the beginning of his heroin habit, as “a slow erosion”. Kilbey’s creativity didn’t falter, though. “At first, I was super creative. I wanted to re-create the drug through music; I was trying to re-create this kind of languid, floating, deep, dreamy feeling.” This goal was best captured on the Church’s 1992 album, Priest = Aura, a remarkable record that remains a fan favourite among the band’s 20 full-length recordings. On the opening track, Aura, Kilbey sings,

Where can a soldier fix himself a drink?

Forget the noise, forget the stink

And the opium is running pretty low

’Cause when the pain comes back, I don’t want to know.

“That was a good one,” he says of Priest = Aura. “That was the honeymoon. That’s when you can hear it; you can hear it’s working. You can hear that I achieved that thing. And then it went downhill after that. For 10 or 11 years, I still made records (on it). But I struggled a bit. When the gear arrived, I’d get so stoned I couldn’t work, either.” The alternative was worse, though, when the drug was in absentia and the singer was hanging out for a fix.

“It was never the best place, but nonetheless I did work,” he states. “And I had to keep working to make money, for the gear. I don’t think the records I made during my heroin phase are the best records I ever made. The band were never very happy about it, but there was not much they could do, either. They couldn’t really kick me out. Whoever was there just had to put up with it. They became tired of, ‘Hey, can I borrow $100?”’

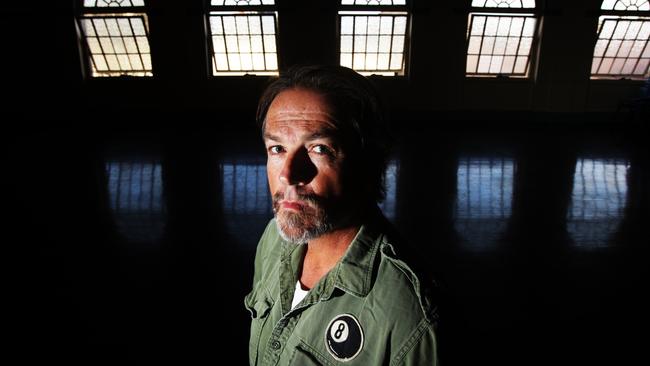

It’s an understatement to describe Steve Kilbey as a gifted conversationalist. The tanned, silver-haired 58-year-old radiates intensity and engagement in the topic at hand. He is articulate, self-aware and funny. He uses simple adjectives such as “idiot” and “ratbag” at unexpected moments, which add to the humour of his storytelling. After he lets me into his bright, two-storey apartment off a quiet street in Bondi on a Thursday morning, I cast my eyes across his full bookshelves and striking artwork hung on the walls. Besides being known for his music, Kilbey is also a talented painter, with a small studio in his upstairs bedroom. Out the window is a view of the nearby hills; the ocean and Bondi Beach can be seen from the balcony.

Kilbey soon makes clear his problem with the volume of my voice. “Listen, after 40 years of rock and roll, I’m a bit deaf,” he tells me as we sit down in the living room. “So speak loudly if you can, ’cause my ears are ringing so loud that to me you sound like …” — he mumbles incoherently to illustrate the point. “All the consonants are disappearing between my woooooo,” he says, imitating the high-pitch noise that he now lives with.

“Tinnitus?” I ask, loudly.

“Screaming tinnitus,” he replies. “Oh well. They told me I’d go deaf, and I did.”

His slow erosion continued throughout 1991. “At the beginning of the year, I was a confident, smart-arse, moneyed-up guy; by the end, I had a lot of people starting to realise I was on the gear,” he says. “I was attracting a lot of ratbags. I’d used up a lot of my money. I’d gone through my “easy cash” — whatever was lying around — and then I started to cash in my super, and my long-term savings. I started rapidly running out of money and hocking guitars.

“Within a year, I was starting to go downhill; within two years, I was a mess, and everybody knew it. I was f..king up tours, borrowing money — stuff like that. It just went down, and down, and down.”

Heroin addicts share an adage among themselves: every habit is worse than your last. Every time you try to quit, then relapse, the effects will be felt more deeply and strongly than ever before. Kilbey tried to quit. He’d tell himself that he wasn’t going to use any more. Then he learnt what heroin withdrawals felt like. “It’s a nightmare,” he says. “There’s not much worse that you could find, probably, other than chemotherapy or something like that. They’re just the most terrible thing. Whatever you fear, whatever you were running from when you were using, that f..king devil comes back in spades when you’re hanging out, feeling bad in every single way, that’s what happens when you’re hanging out. You’re so anxious and desperate to make it stop.”

This stark contrast between the highs and lows of addiction fascinated Kilbey. He’d be desolate in the absence of the drug, clutching his aching head and body, thinking to himself, “The whole world’s going to end, my girlfriend and children have left me (his partner took their identical twins to Sweden at the end of 1993) — I’ve got no money, I’ve hocked all my guitars.” But then he’d “fix” himself, fully aware of the irony of that term. His eyes would brighten. The dark cloud would lift. Watching him act out this seesawing emotional state, a by-product of chemical dependence, I’m struck by his vivid portrayal of the agony and the ecstasy.

Friends and family tried to stop him. There were attempted interventions. At one point, his mother — “an old English woman, who’s drunk ten cups of tea every day of her whole life” — phoned with an offer: she’d give up drinking tea if he kicked heroin. “She was looking for an addiction trade-off,” he says. “But even that — nup. Nothing was going to stop me.”

A move to Sweden, to be closer to his twin daughters, didn’t help the situation: it was easier than ever for Kilbey to score. “In Australia, you had to know a dealer,” he says. “It was always this hassle; you’d have a dealer, but they’d (eventually) get busted. Or you could go out to Cabramatta (in Sydney’s southwest). But in Stockholm, I bought a flat right in the middle of the city. One train station away was Central Station. You just turned up at Central and there were always like a dozen dealers down there.”

He had a few run-ins with the local constabulary there, too.

“I got busted in Sweden a couple of times. They didn’t really know what to do with me.”

Luck doesn’t last forever, though, as Kilbey found out while on tour in New York in October 1999. “I wasn’t even a junkie at this stage,’ he says. “I was in an in-between stage.

“A friend of mine rang me up and went, ‘Man, there’s some good smack down in Alphabet City!’ So I went down there, I bought some smack, and a cop (saw) me buying it. I went to jail for the night.”

As a result, Kilbey missed a Church show on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. “More than 200 fans waited at the Bowery Ballroom on Delancey Street for the 10pm start,” wrote Michael Cameron in The Daily Telegraph on October 7. He went on: “At 10.35pm lead guitarist Marty Wilson-Piper nervously walked up to the microphone to reveal the news. ‘I’m not sure how to say this, but we have a problem,’ Wilson-Piper said. ‘Steve isn’t here. In fact he won’t be available tonight. He’s been arrested.’ ”

The following day, Kilbey had a court appointment. His legal aid was evidently a fan of the Church. “He came in and said, ‘I know who you are, mate. I’m going to sort you out,’ ” Kilbey tells me. “He went up and told this sob story: ‘My client’s a musician, he’s under a lot of pressure, he’s away from home, he’s become addicted to drugs as an entertainer, he’s really sorry …’ The judge was like, ‘Well, Mr Kilbey, I know they don’t like heroin down in Sydney either, so I don’t know why you’re coming to New York and using drugs. This is your first offence here, so I’m just going to give you a day’s community service.’ ”

Kilbey maintained a sense of humour about the incident: a Daily Telegraph article from October 8 describes him emerging: “from room 103 of the Manhattan Criminal Court slightly dishevelled but otherwise unfazed over his experience with the US legal system … He said being picked up for drugs in New York was a rite of passage for Australian musicians. ‘A drug bust is something every aging rock star should have under his belt,’ he said. ‘Nick Cave and I are in great company.’ ”

“That’s right!” he says. “It wasn’t bad for business. I made the second page of The Australian.”

How Kilbey shook off his 11-year addiction is a curious tale. While planning to leave Sweden and again set out for America, he stopped injecting the drug and switched to snorting, and bought a bottle of methadone that he mixed with cough syrup. “When I got to America, I tapered down on the methadone until I was just having an eighth of a teaspoon full,” he says. “When the methadone ran out, my body had tapered off enough so I didn’t get any of the severe physical effects; I just had a long period of profound depression and anxiety. I felt like I was a hundred years old. Just to stand up and walk up a step was so much effort. I was so tired, but I couldn’t sleep — insomnia. But my last withdrawal wasn’t that bad, because of the methadone.”

While in the US, living in a small town with the mother of his second set of twins, Kilbey couldn’t find heroin. He didn’t expect to, either, which is why he’d planned ahead with the methadone. Upon returning to Stockholm four months later, though, he immediately visited Central Station, took the drug home. Something strange happened. Instead of the warm, “cushiony” feeling he’d known for over a decade, he felt the opposite: itchy; restless; headache; sickness. It was the first time that he’d had a bad reaction to the drug. “It was almost like the smack had said, ‘I’m tired of you’.”

“Something happened. After my eleven years in hell and purgatory, it’s like the universe went, ‘All right, we’ve knocked a few rough edges off you. Right, you can come out.”’ He describes this outcome not as his decision to give up heroin; instead, he says, ‘heroin gave up me’.”

Since that moment, around 2002, Kilbey has had the occasional taste. ‘I think probably last year I had a snort,’ he says. ‘And nah, it doesn’t do it for me. I have no temptation. I’m just not interested anymore. If you put a bowl of it on the table, I’d go, “Oh, I don’t know what to do with it.”

As our eighty-minute conversation starts to wind down, talk turns to other substances. ‘I think there’s only one drug on this earth I haven’t tried yet,’ he says. ‘And that’s ibogaine, which is a drug that’s made from a bark in Africa that pygmies take at their initiation. I think that’s the only substance I haven’t had.’ We discuss dimethyltryptamine – DMT, for short. It’s a psychedelic drug.

He opens his laptop and begins showing me an art exhibition that he staged in Yellow Springs, Ohio, in 2008, entitled The Empty Place: A Modern Australian Psychedelic Vision.

The twenty-one paintings were inspired by taking DMT and ayahuasca, he says, the latter being a psychoactive brew that originated in South America. I’m no art critic, but I like what I see: bold, colourful borders, striking human faces – including a few more self-portraits – and a recurring theme of blue, human eyes that surround the characters, all-seeing.

It strikes me that I’m in the presence of an unrepentant drug fanatic. Kilbey’s enthusiasm for the topic is so bald, his experiences so vast, his ability to articulate altered states through art and conversation so refined, that it’s fascinating to be in his presence as he narrates a lifetime of drug use.

‘We let people have booze, cigarettes, wars,’ Kilbey continues. ‘We let them have fluoride in the water, and all the rest of it. Why not let them have smack? People used to take it, and it wasn’t seen as a problem. If you lived in 1890 and you were an opium fiend, that was your problem: to take it, and to find out how to stop taking it. It was nothing to do with the law.

There weren’t people wagging their fingers at you. It’s just something that you embarked upon. It had its joys and perils, just like anything else.

‘Now, I’m not going to sit here and go, “Oh, kids, look what I did to my life because I was a drug addict. Please don’t be like me. Please be Mister Straight.” I don’t believe in that, either. I think we have to grow up and look at why drugs are illegal.

“I’m a pretty model citizen. I’ve written the most popular Australian song of the last twenty years’ – ‘Under the Milky Way’, that is, as voted by music critics and fellow musicians in The Weekend Australian Magazine in 2008 – ‘I play shows all around the world. I donate my money to charity. I’m involved in the community with the school. I’m a trustworthy guy, a good guy. And I happen to take drugs.”

He pauses, choosing his words carefully. “I just don’t want people to believe the hype, that if you take drugs you’re necessarily an evil villain. You might be a silly person, or a weak person. But you’re not a bad person.”

Talking Smack, by Andrew McMillen, is published by University of Queensland Press.