The case for the small but real worth of strange daily routines

When ill health and family drama stopped philosopher Damon young from competitive fencing he committed to a unique daily ritual to surprising results.

You finally finish your day at work, weary and hungry. Walking home down the hill, you enter the park. The river’s lapping will calm you. The bright, distant hills will offer a holiday from your cubicle’s drab corkboard.

You cross the little bridge over the rivulet, watch the ducklings swimming and then ...

You’re confronted by a man swinging a sword.

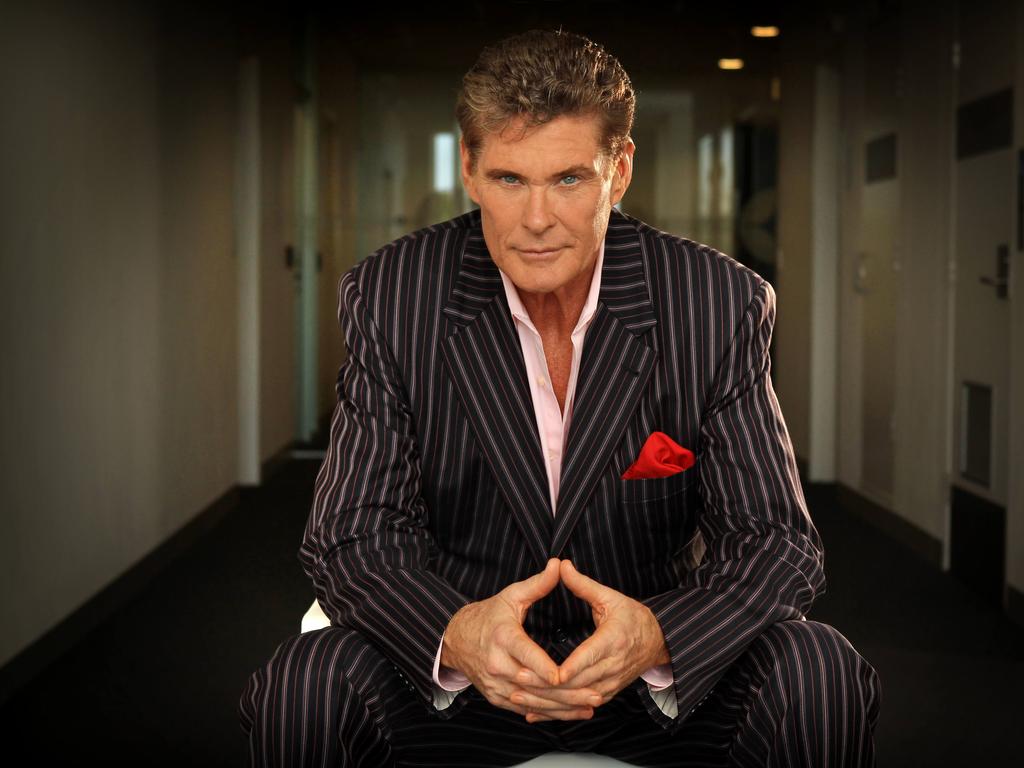

Hello, that’s me. I’m the man swinging a sword. But why?

This story began when I was a teenager. Thinking that I needed to defend myself, my parents sent me to a karate school. And I did defend myself over the years, though not always perfectly (I still have the scars).

At university I studied philosophy, fighting less with fists and more with syllogisms. But I continued studying martial arts because they were physically and intellectually stimulating. I enjoyed the collaboration, practising violence without malice. I enjoyed the cardiovascular jolt of sparring and drilling.

I valued the martial virtues: courage from facing danger, perseverance from enduring pain, humility from suffering failure.

So, training to fight has had at least two clear benefits for me: protecting myself from harm and cultivating my character.

I’ve been thinking about both for much of my adult life, even editing two books on philosophy and the martial arts. I’m intrigued by the craft of combat.

And this is why I was hoisting steel by the river. For some years now, I’ve been training in historical fencing.

Like modern fencing, this involves simulating duels with consenting opponents. But the emphasis is much more on surviving melees rather than scoring points.

Yes, we wear padding and use blunt blades. Yes, we have competitions. But the tactics, strategies and lexicon are taken from historical European manuals, written when duels were a fact of life for gentlemen (and some ladies).

My chief style is from a how-to guide written by George Silver, a Renaissance Briton who loved the English broadsword and loathed those fancy, rapier-wielding Italians.

Over a year ago, I had to take a break from historical fencing for various reasons: wounds, ill health, family drama.

And I felt that my sword arm was losing its strength and suppleness. So I set myself a challenge: every day of last year, I had to make at least 35 cuts in the air with a sword. This covers most of the cuts on both sides: descending, rising, horizontal.

I could use any of my swords: broadsword, rapier, longsword, sidesword, and so on. I could do it morning or night, outside or inside. (Only one lampshade was broken.) And I could add parries and thrusts.

But I had to do this every day, regardless of whatever else I was doing.

And I did. Over 12 months – and two homes, four manuscripts, various crises – I performed a minimum of 12,775 cuts. Probably double this, as I often did my drills twice over. But what did they do for me?

Most obviously, my sword arm did seem to keep its force and agility, even when I wasn’t training.

Yes, I had tendinitis and bursitis before, and I have them after. Yes, I grow old. But I returned to training for the weekly competition and came equal second – not bad after so much idleness, and against those who had been training regularly. (Alas, I also hurt my shoulder foolishly in the last bout. More of that humility I mentioned.)

Yet I learned more in my year of cuts than merely how to keep up my sword arm. And what I learned had value beyond the martial.

Most basically, my daily cuts left me more lucid. They offered a holiday from the cumulative fuzziness of work.

I gave myself over to the effort and returned with clarity and enthusiasm.

I also felt freer after my cuts – less weighed down by torpor. The logic was this: if I could wrench myself from the couch to swing around a kilogram of steel in the rain, then I was capable of all sorts of agency. Yes, I laboured, showered, cleaned, cooked. But doing the utterly superfluous took more liberty.

I gained a better idea of habits, and how responsive they can be. Yes, I did my cuts daily. But I varied them considerably.

I changed my pacing: sometimes fast for a workout, sometimes slow for better form. I shifted my distance: short, tight grapples and long, loose cuts. I trained on smooth floorboards, soft carpet, squishy grass.

And I noticed how these were affected by, and affected, my moods. On bad days, I wanted nothing more than to hack and slash – the clumsy frenzy of stifled hope. My cuts became a fleshy archive of my states-of-mind.

I also realised people are far more curious than afraid. Strangers approached me enthusiastically – and not just the dogs who thought I was throwing a stick.

A mum brought her two kindergarteners to watch, the kids bouncing on their toes and begging for a turn with the brass-hilted knightly sword. A muscular guy borrowed my longsword and performed a tight, twirling form. International students from Europe and Asia asked where they could train too.

A ballerina in her 70s compared foot positions with me: hers with toes turned out, mine with the toes tucked in.

In this way, my movements became prompts for conversations: about the markers of class and status, the felt beauty of performance, the ethics of violence as play. My physicality invited everyday philosophy.

I’m not proselytising for swords here. Well, I am – always. But my points (so to speak) are also about secular rites, domestic rituals. I’m making a case for the small but very real worth of strange daily routines.

They’re not just about practice, they’re about how this practice fits into a changeable life; how it encourages some thoughts and feelings and not others; how it gathers small revelations around it.

Sometimes the best thing after a long day at work is the edgy pursuit that awaits you.

Damon Young is a philosopher and author. His latest book is On Getting Off: Sex and Philosophy (Scribe)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout