The brutal truth behind Australia’s most famous arrest of ‘Succulent Chinese Meal guy’ Jack Karlson

The 'star' of one of Australia's most-watched arrest videos, Queensland man Jack Karlson, has died aged 82, after a reported battle with prostate cancer. Mark Dapin recalls meeting the man who launched a thousand memes.

This story was first published in 2023.

When I was 20 years old, I was bashed in a police station in England. Much later, I wrote a newspaper column about unusual places I had been beaten up – including a bookshop, a bus stop, and Wales. I didn’t mention the police station, perhaps because I didn’t consider it unusual.

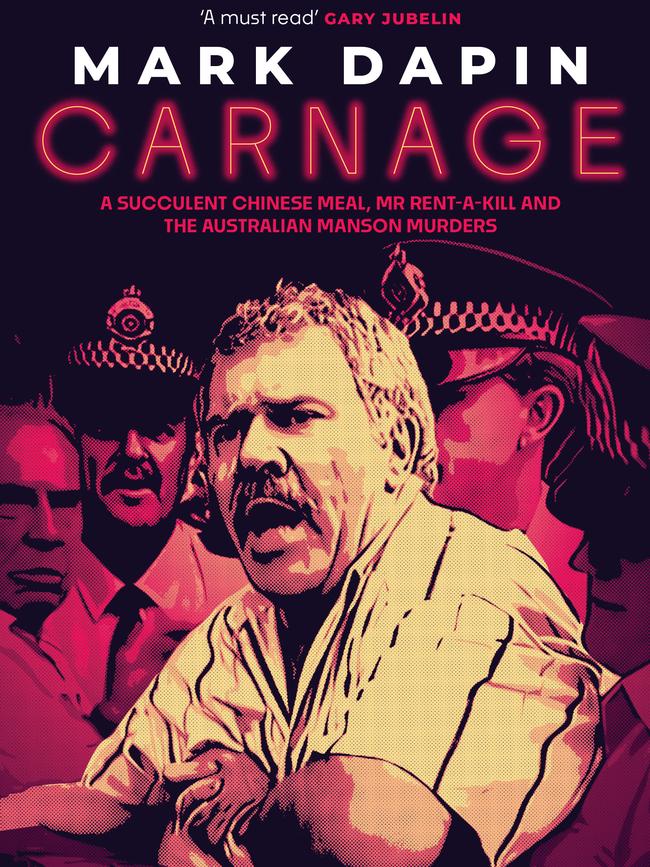

I’ve never written about the bashing, and I’d hardly thought about it until I started working on my new book, Carnage: A Succulent Chinese Meal, Mr Rent-a-Kill and the Australian Manson Murders.

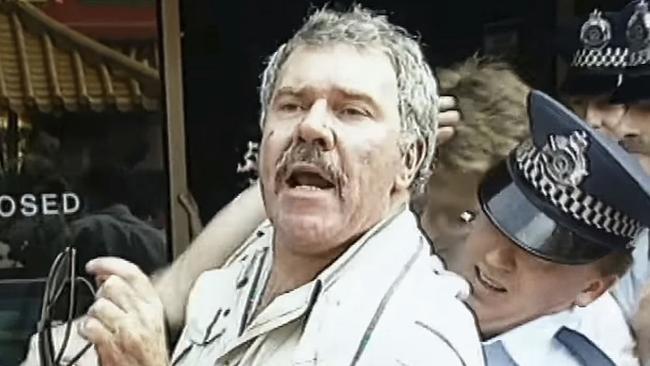

It features Jack Karlson, who is the “star” of the most-watched arrest video in Australian history. He called me just as I was boarding a coach to Canberra. I didn’t know who he was, but it turned out that more than 3.2 million people have to date viewed the clip that appeared (somewhat mysteriously) on the internet in 2009, in which a burly, outraged diner is apprehended by police at a restaurant in Brisbane in 1991.

While plainclothes and uniformed officers struggle to load their prisoner into a car, he creates a spectacle of magnificent defiance for the waiting television cameras. “Gentlemen,” he proclaims, stentoriously, “this is democracy manifest!”

He demands to know the charge: “Eating a meal? A succulent Chinese meal?”

As the police struggle to subdue him, he bellows, “Get your hands off my penis!”

And so a legend – or, at least, an internet meme – was born.

I had never seen the video, variously known as “Democracy Manifest” and “A Succulent Chinese Meal”, though I later found out that my son had studied the clip in English lessons at school.

Over the phone, Karlson told me he had heard that I was writing a book about prison breaks, and he felt that his own escapes from custody deserved to be included. I told him I’d finished the manuscript for that book, but he insisted I visit him in Queensland anyway. He was persuasive – charming, self-deprecating, with a brutal bonhomie – but I was busy with other projects.

A little later, I received a call from an ex-prisoner I know, who described Karlson as the most interesting criminal I would ever meet. And so, the next time I was in Brisbane, I went to visit Karlson. He was living at the end of a dirt road, on a bush property that featured an unplumbed spa bath (it looked as if it had fallen out of a plane) and a partially plumbed shipping container.

He told me about his prison time, and his prison escapes, which were creative, non-violent and wildly unlikely.

On one occasion, he had been taken to court with his co-offender and, while they were both in a holding cell, he had disguised himself as his own arresting officer and escorted his mate out of the building to freedom.

It was fascinating and funny, but I only realised who Karlson actually was towards the end of our meeting, when he told me that his wife had been murdered.

I knew from my research for my prison escape book that a young woman named Eve Karlson had been killed in 1978, after aiding the escape from custody of Barry Quinn, a criminal sometimes known as “Australia’s Charles Manson”.

I knew that Quinn’s escape and Eve’s death had led to a string of further murders involving at least two serial killers. Some time earlier, I had resolved never to write the story because none of the living characters seemed to have any good in them at all.

In my life, the decision not to do something is generally the best predictor that I will do it.

■ ■ ■

I mentioned earlier that I was once bashed in a police station. It happened after I was arrested in England in 1983, late in the evening after I’d had an altercation with security guards who had called the police, who wanted to charge me with being drunk and disorderly (unfair, since I was not drunk, merely disorderly). When I refused to give a police officer my name, he grabbed me by the neck. I tried to push away his hand and he punched me in the mouth.

My head bounced off the station wall and I fell to the floor. My lip burst like a water pipe.

I asked the cop how he was going to explain what he had done to my face. He told me I would be charged with assaulting a police officer.

Many years later, my mum was going through my things when she found a photograph of me after that bashing.

“Who’s this?” she asked.

His own mother didn’t recognise him. Some months after I met Jack Karlson, I began work on Carnage, which features the story behind the Democracy Manifest video, Karlson’s prison escapes, the murder of his wife and the barely believable human destruction that followed.

When I was researching it, and criminals spoke to me about being bashed by police, I usually believed them. Because they’ll take you down a peg or two, the cops will. They’ll show you who’s boss.

Or, at least, they would back in the day.

On the night I was arrested, I was locked up alone in a bare police cell, bored and uncomfortable and out of cigarettes. I realised I might be looking at a jail sentence for the imaginary assault, but I was more angry than scared. All night long, I leaned on the emergency buzzer and asked the police for more smokes.

So when I was researching Carnage and ex-prisoners told me about unlikely acts of defiance committed in jail by men such as Christopher Flannery, the reputed assassin who became known as “Mr Rent-a-Kill”, I was inclined to give credence to their stories because I knew that even a coward like me found it difficult to back down when somebody was trying to make you feel helpless and subdued.

Flannery was a former friend of Karlson, as were a great number of other identities in the criminal world – as well as many writers, artists and actors. Karlson had led a startling life and, I was to discover, it was at least possible that he had anonymously contributed to the writing of a famous play and the creation of some moderately well-known paintings, as well as being shot in the leg by one of Australia’s best-known gangsters.

In the days when Karlson was an active criminal, police routinely verballed suspects whom they believed to be guilty of serious offences. That is, detectives fabricated confessions that they swore that the offender had made but subsequently refused to sign.

Any author could tell from the identical syntax and vocabulary in statements attributed to an entire generation of professional criminals that they were reading a piece of creative writing, populated by stock characters mouthing set phrases to predictable effect. Jack Karlson claimed to have been often verballed. Chris Flannery seems to have been sometimes verballed. Barry Quinn, “Australia’s Charles Manson”, was comically verballed, his false confession to a double murder carefully constructed so that he could make no successful defence.

And I was verballed in court both by the police and the security guards. They made me sound like a deranged moron. They said I’d called them f--king c--ts, which is what they had called me, which is why I had refused to give them my name in the first place.

They made me sound like them.

So when I heard that someone had been verballed, I knew how they felt to face jail on account of something they had never said.

Because I could have gone to prison for assaulting a police officer, back in 1983.

In the end, however, I wasn’t charged with assault – just drunk and disorderly. I accepted a bond to keep the peace; if I were to be arrested again within the year, my case would come back to court.

I stood up in court and tried to tell my side of the story – how the police evidence had been fabricated and I had been bashed – but that wasn’t part of the deal.

When I read a trial transcript of Karlson attempting to do the same thing – as prisoners often did – I felt for him. Sure, he was probably lying about his offence, but everybody else in court was lying too. Why should Karlson be the one who wasn’t believed, just because he was moneyless and powerless and had no rank or uniform?

That night of mine in Tile Hill Police Station in Coventry in the West Midlands, in the same year that a man named James Davey died after a struggle in another Coventry police station, could have wrecked my life. But it didn’t change anything. I didn’t even draw any lessons from the experience. I didn’t come to hate the police. I didn’t join the Justice for James Davey campaign. I didn’t become any more respectful to security guards.

The only thing I have ever done is use it to help me write Carnage. So, almost 40 years after the police officer dropped me with a practised right hand, I’m thankful that it happened.

Carnage: A Succulent Chinese Meal, Mr Rent-A-Kill and the Australian Manson Murders by Mark Dapin (Scribner) is out August 2. Mark Dapin is a journalist, author and screenwriter whose books include Spirit House, which was longlisted for the Miles Franklin. He also writes crime, and military history.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout