The Blak Infinite’s art installations explore First People’s futures as part of the annual Rising festival

Dynamic cultural figure Tony Albert will take centre stage with a work resembling a comical alien invasion ... until you look closer.

Tony Albert has been fascinated by sci-fi since he can remember. He was infatuated with aliens during high school; in the early 2000s he took part in a football carnival and named his team “the Austra-aliens”, and an obsession with The X-Files and the pop culture image of the large-headed green, almond-eyed alien inspired his conceptual research at Griffith University where he studied visual arts. Soon enough, playful images of otherworldyly beings and sci-fi began regularly appearing in his work as a practising artist.

So when senior curator and Yorta Yorta woman Kimberley Moulton invited him to take part in The Blak Infinite, a large-scale collection of art installations in Melbourne’s Federation Square that explored First People’s futures, connections to the cosmos and political discourse as part of the annual Rising festival, Albert didn’t need to think twice.

“It’s outside, it’s part of a festival, and with everything being tough at the moment I wanted something people could interact with, something that was really fun and that I could transform into this abduction site. I was completely keen from the get-go,” Albert says.

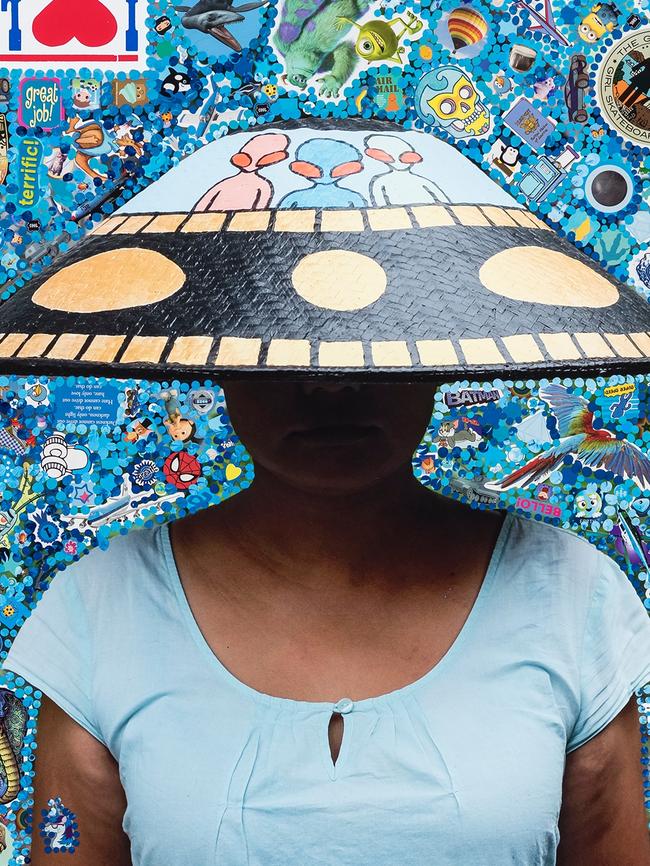

Albert’s multidimensional work, Beam Me Up The Art of Abduction, resembles a comical alien invasion that will see a flotilla of 3m, two-dimensional colourful cartoon spaceships hung at rakish angles around the atrium, its triangular architecture lit to resemble rays of light emanating from the vessels ready to “beam up” members of the public (all of it very Instagrammable, of course). Albert is also creating a large-scale video piece for the live screen, an edit of various works from his back catalogue.

It is all fun and playful and inclusive until you go a bit deeper and appreciate the themes Albert is exploring: the idea of first contact, colonial takeover, destroying planets, the question of belonging and who the alien really is.

The highly respected Brisbane-based artist and ambassador for Indigenous culture and community has a multidisciplinary practice, creating art that regularly tackles the cultural misrepresentation of Aboriginal people, typically through humour and optimism.

“One of the biggest things in my work is the idea of equality being the acceptance of difference. Things don’t have to be the same for them to be equal,” says Albert.

“I hope people know and can understand and grapple with that in their own way. It’s not about yelling and screaming, it’s just about planting these seeds.”

In programming The Blak Infinite, Moulton was keen to include Albert not only because of the vast body of aligned work he could draw upon, but his ability to spark conversations through his art.

“Tony’s earlier work that features aliens looks at ideas of belonging and citizenship and what it means to be alienated in your own country,” Moulton says. “There’s a lot of play within the work but provoking that very important conversation we continue to have in this country, especially post-referendum.”

A writer and Rising’s artistic associate, Moulton has programmed The Blak Infinite with curator and artist Kate ten Buuren (Taungurung). The free two-week exhibition and public program will feature as a centrepiece Richard Bell’s EMBASSY, an installation inspired by the Aboriginal Tent Embassy pitched at Parliament House in 1972 that has since toured the world in various iterations, from London’s Tate Modern last year to Documenta, in Germany, in 2022. EMBASSY will be accompanied by politically driven daily film screenings and weekly artist, activist and community talks.

Other artworks include Sky Country by young artist Tarryn Love and Indigenous animation company Studio Gilay that will light up the night sky with projections focusing on the connection between Country and the cosmos and two new text-based works written by prolific writer and thinker Ellen van Neerven, responding to the themes of The Blak Infinite, that have been animated and will be screened.

There will also be various works by Kait James inspired by Albert’s work that take a critical but good-natured look at the sort of 1950s Aboriginalia found on tea towels and other touristy paraphernalia as well as exploring sci-fi, projected on big light boxes; alongside fantasy worlds created by Michael Cook that re-create the idea of invasion, flipping the script to depict scenes of Indigenous people, possums and lizards taking over London.

“It’s speculative fiction, there’s lot of humour and play and it provides a different perspective on history,” Moulton says. “We wanted to take over Federation Square, and profile and amplify First Nations art and voices … looking at the infinite possibilities of who we are as Indigenous people.”

Moulton is in a prime position to know what she is talking about. A former curator at Museums Victoria, she was last year appointed adjunct curator of Indigenous art at Tate Modern as part of its ongoing strategy to explore new perspectives on global art histories. Her appointment, she feels, is just the latest move to rectify the absence of Indigenous voices: within global exhibitions, within art history and within institutions themselves.

And not before time.

“There’s a genuine commitment from the Tate, and it’s building globally, to address (this) absence and to genuinely form connections with the people who have the expertise and the lived cultural experience,” Moulton says, pointing out her remit at the Tate extends beyond merely Australia and the Pacific to the world’s Indigenous people, from Norway to North America. “It’s not tokenistic, we’re seeing genuine change. Change takes a long time, it’s not just going to take one or two people getting hired to make that happen, it’s long-term, long-game strategy.”

Moulton was at the Venice Biennale at the very moment Kamilaroi/Bigambul artist Archie Moore was awarded the Golden Lion for Best National Participation for his work kith and kin, the first Australian artist to win what is regarded as one of the international art world’s highest honours.

“Everyone was overwhelmed, not just the Australians,” she says. “It feels like a shift, with the representation there (of an Indigenous artist) and the inclusion of Indigenous artists within the curated exhibition and pavilions, countries themselves bringing and highlighting Indigenous practice. It’s a pertinent issue right now, to be looking at Indigenous knowledge, not just for climate and the environment but the social situations we’re having to consider.”

Next year Tate Modern will host a solo exhibition of artist Emily Kam Kngwarray, the first large-scale exhibition of the late artist’s work in Europe. “This (exhibition) encapsulates what Tate Modern is all about: celebrating the world’s most significant artists – those who shape international art history, speak to our times, and imagine new futures,” Tate Modern director Karin Hindsbo said when announcing the exhibition; while in late 2022 the Indigenous Brisbane art collective proppaNOW – of which Albert and Bell were founding members in 2003 – was awarded the esteemed Jane Lombard Prize for Art and Social Justice in New York.

Albert, too, is cautiously optimistic, not only about Indigenous arts and culture being broadly acknowledged and celebrated but that Indigenous people are gaining a voice through institutional representation. Albert was the first Indigenous trustee at the Art Gallery of NSW, a position he continues to hold; while last year he was appointed the inaugural Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain First Nations Curatorial Fellow.

The result of a partnership between the Biennale of Sydney and the Fondation Cartier (a private cultural institution whose mission is to promote contemporary artistic creation to the international public), the role means Albert will advise on and help promote future First Nations artist commissions and collaborate closely with visiting First Nations artists.

There were 14 new works by First Nations artists commissioned for the current iteration of the Biennale. “This partnership reflects our belief in empowering First Nations communities to share their truth and underscores the crucial role of listening to their voices as we navigate the challenges of our planet,” said artistic managing director of the Fondation Cartier Herve Chandes.

“First Nations artists bring their rich cultural heritage and unique artistic tradition to the contemporary art scene.

“Their innovative approaches and storytelling techniques can enrich the artistic landscape and challenge conventional norms in the art world.”

Just as Tate Modern has done, AGNSW has appointed a curator of First Nations art (local and global), Erin Vink; while Brenda Croft was in 2022 appointed to the prestigious Gough Whitlam and Malcolm Fraser chair of Australian studies at Harvard.

“We haven’t got it right yet but it’s pretty amazing to see within the realms of global Indigenous art that it’s Australian people who are having these roles internationally,” Albert says. “When we have big international conferences and get-togethers, as much as we feel behind and that there’s much to be done, other countries are in awe of what’s being done. We have penetrated major institutions and are working and are involved.”

“There’s been immense progression over the years,” says Moulton. “But there’s still a long way to go.”

Moulton and Albert agree there needs to be educational and institutional support at the grassroots level, encouraging, nurturing and supporting future Indigenous leaders.

“Curation is just one of hundreds of different opportunities within the art world. We have to go to an educational level,” Albert says. “Our children are pushed into trades, no one looks at the arts as a viable (career) and I think it’s the exact opposite. But we need to nurture them and make sure they know and understand the long-term engagement they can have.

“Our whole structure and way of thinking needs to go back to the drawing board. Yes, there is a groundswell – but we need to learn from it and understand where we’re going.”

The Blak Infinite, free, runs at Federation Square from June 1-16 as part of Melbourne’s Rising Festival.