The best books of 2020 in time for Summer reading

It’s been a year to reflect and a year to read, so read we did! Here we present the 2020 reading lists from writers and critics.

Welcome to our annual Books of the Year, in which writers and critics name the books they read this year that they would most like to share with other readers. As always, the only rule is the book had to be read this year. Its date of publication is not a factor. Hence I can say one of the best books I read in COVID 2020 was from 1963: Pierre Boulle’s Planet of the Apes. I had not read it before and I was pleasantly surprised by how much funnier it is than the film adaptations. I also found a lot more, today, in rereading Albert Camus’s The Plague, an out and out masterpiece.

Here’s the rest of mine. The best novels I read in 2020 are Andrew O’Hagan’s Mayflies, Sofie Laguna’s Infinite Splendours, Trent Dalton’s All Our Shimmering Skies, Kate Grenville’s A Room Made of Leaves, Emma Donoghue’s The Pull of the Stars, Tom Petsinis’s Fitzroy Raw, Tom Keneally’s The Dickens Boy, Douglas Stuart’s Booker Prize winner Shuggie Bain, and Kevin Barry’s Night Boat to Tangier.

In nonfiction I loved Darleen Bungey’s biography of her father, Daddy Cool: Finding My Father, the Singer who Swapped Hollywood Fame for Home in Australia, Robert Dessaix’s wry account of ageing, The Time of Our Lives, and the essay collection Animals Make Us Human, edited by Leah Kaminsky and Meg Keneally. I was blown away by Christos Tsiolkas’s essay, Class, Identity, Justice: Reckoning With the Ghosts of Europe, in Griffith Review 69: European Exchange. I was deeply impressed by Alex Miller’s Max, as I am by everything he writes, and, as someone who does not know a lot about art, captivated by Julian Barnes’s The Man in the Red Coat. In poetry, I recommend Jaya Savige’s collection Change Machine, and Clive James’s essay on poems he loved, Fire in the Sky.

Having now read everyone else’s recommendations I realise my next must-read book is one I had not heard of (for which Geordie Williamson might demand my head): M. John Harrison’s novel The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again. And with that, it’s time to hand over the mic.

-

Carmel Bird, novelist

On March 24, quite by chance, I took from my bookshelf an old green book, Tales From Uncle Remus. It was a gift from an aunt when I was six, and was the first book I read from cover to cover, albeit with difficulty. It set me off on an adventure of reading the many books from childhood still in my possession. I then decided that during the lockdown I would read only books found in my house, letting one lead me to another in a random way.

I have broken the rule only once. In May I wanted to re-read The Bridge of San Luis Rey. I knew it was here, a little grey book, but it had disappeared. I called the local second-hand Book Heaven who delivered that night to the door like a pizza. A handsome old blue book with Thornton Wilder’s autograph engraved in gold on the cover. On November 10, an inconspicuous bright emerald green book manifested on a shelf, and yes, it was The Bridge of San Luis Rey. So much for memory. Oh, the things I have read. Everything from Gilgamesh to Thea Astley to old and new Martin Amis.

-

James Bradley, novelist

Despite the rolling chaos of the past nine months, there’s no question 2020 was a bumper year for books. Among the real standouts on the fiction side were Douglas Stuart’s wrenching and almost unbearably raw Shuggie Bain, Hilary Mantel’s extraordinary The Mirror and the Light, and Andrew O’Hagan’s beautiful exploration of youth and ageing and loss, Mayflies. But I also adored the final volume in Ali Smith’s magnificent Seasons Quartet, Summer, and M. John Harrison’s marvellously strange and hypnotically sinister Goldsmiths Prize winner, The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again, Laura Jean McKay’s gloriously feral The Animals In That Country, Kate Mildenhall’s The Mother Fault, and Jock Serong’s The Burning Island.

Of the nonfiction I read I hugely admired Merlin Sheldrake’s exploration of the wonderfully weird world of fungi, Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds and Shape Our Futures, Julia Baird’s simultaneously expansive and grounded Phosphorescence: On Awe, Wonder and Things That Sustain You When The World Goes Dark, Rebecca Giggs’ prismatic Fathoms: The World In The Whale, and Craig Brown’s delightfully witty biography of the Beatles, One Two Three Four. And finally three books of poetry: Felicity Plunkett’s A Kinder Sea, Hannah Sullivan’s Three Poems, and Claudia Rankine’s stunning Citizen.

-

Simon Caterson, writer and critic

One of my most anticipated books this year was Alex Frayne’s Landscapes of South Australia. There is a formal austerity, an astringent stillness about Frayne’s work that combines with the characteristic flat dryness of the terrain to conjure a hypnotic visual essay at once serene and sublime. The book confirms that Frayne, who uses old cameras and expired film in his artistic practice, deserves to be thought of alongside Ansel Adams and the other great landscape photographers.

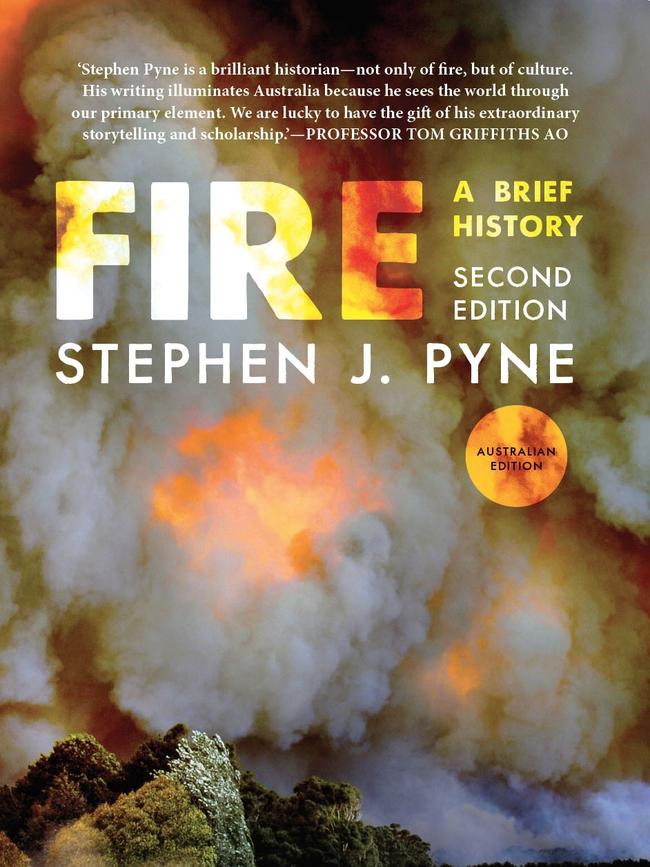

Another important event in my reading life was the publication of a new Australian edition of Stephen J. Pyne’s seminal Fire: A Brief History. Based in Arizona, Pyne is a leading international authority on the history of wildfire. The new edition includes a preface reflecting on the bushfires of 2019-20 that sent smoke drifting right across the world. According to Pyne, this catastrophe could mark the beginning of a new age he calls the Pyrocene.

He believes that Australia, which has a unique intimacy with fire going back millennia, has the ability to lead the rest of the planet in the effective management of this increasingly widespread and destructive global phenomenon.

-

Trent Dalton, journalist, author and critic

Maybe the most moving literary moment for me in 2020 occurred at the Northern Territory Writers Festival in October when writer Thomas Mayor gave a note-perfect memorised recitation of the Uluru Statement From the Heart. It was direct, it was electrifying and it was, indeed, from every bit of his heart. I bought his book, Finding the Heart of the Nation, about half an hour later and found it every bit as moving, and motivating, as his oration that day.

Mirandi Riwoe moved me greatly with Stone Sky Gold Mountain when she spirited me away to the world of Chinese settlers in late-1800s Queensland. Dervla McTiernan’s The Good Turn and Kate Mildenhall’s The Mother Fault thrilled me equally for wildly different reasons. My go-to cure for the coronavirus blues was Craig Brown’s One Two Three Four: The Beatles in Time, a collection of remarkable non-linear vignettes — the postman who killed John’s mum; the sad ballad of brief Ringo sub, Jimmie Nicol — that form a magnificent matrix tribute to Liverpool’s fabulous miracle.

-

Kate Holden, author and critic

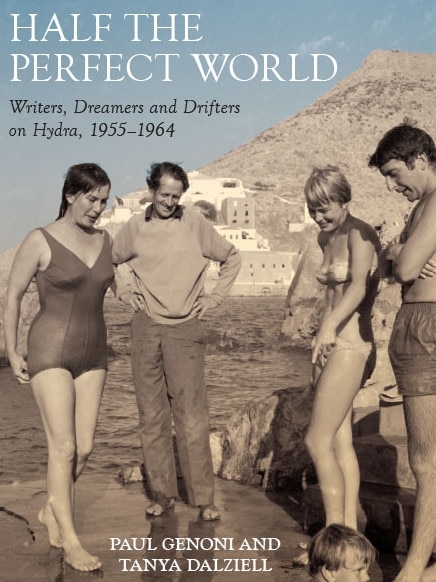

This year I spent a lot of time mentally far away and long ago, first in the expat dream of 20th century Greek island bohemia: Lawrence Durrell (Prospero’s Cell) and Henry Miller (The Colossus of Maroussi), and Robert Dessaix (his eponymous novel) in Corfu; Leonard Cohen, Charmian Clift and George Johnston on 1960s Hydra. I read their own works, and Half the Perfect World: Writers, Dreamers and Drifters on Hydra 1955-1964 by Australians Paul Genoni and Tanya Dalziell, and then Polly Samson’s new gorgeous fictional version of that clenched idyll, A Theatre for Dreamers.

Armchair excursions to the Steppes, to Russia and Mongolia, then I followed Cohen to 1960s New York with Patti Smith’s memoir Just Kids, and Sheryll Tippins’s account of the Hotel Chelsea. I dawdled in 1950s Paris for an obsession with Simone de Beauvoir, reading her enormous and surprisingly satisfying The Mandarins (1954) and three biographies of the woman. Winter was spent in Europe’s Middle Ages with Simon Winder’s implausibly entertaining recent Lotharingia, and Samantha Harvey’s medieval murder tale, The Western Wind. But I ended back in Australia, discovering the late Beverly Farmer’s lucid quietude, and inspired by Dumbo Feather magazine to plan for a lustrous future from the here and now.

-

Sarah Holland-Batt, poet and critic

2020 was a stellar year for Australian poetry. Among my top picks is Jaya Savige’s restless and brilliantly inventive Change Machine, in which the poet toggles between high and low registers with warp speed, pairing the laconic (“London, the sky sits on your face / like the distressed arse / of a XXXL pair of stonewashed overalls”) with the esoteric. In Savige’s intelligent, densely allusive poems, Leopold Bloom from Joyce’s Ulysses brushes up against the NASCAR Thunderdome, and surfers at the Quicksilver Pro jostle with Vikings and Tahitian kings in Teahupo’o. Indigenous poetry is celebrated in Alison Whittaker’s outstanding anthology, Fire Front: First Nations Poetry and Power Today, which pairs poetry with powerful and probing essays by leading Aboriginal scholars, writers and thinkers.

It was also great to see Martin Johnston’s selected poetry published in Beautiful Objects: an anthology that reminds us of Johnston’s singular perspective and style on the 30th anniversary of his death. I also loved PiO’s epic Heide, a poetic biography which launches the reader into the hedonistic orbit of Sunday and John Reed at Heidelberg, but which spins out to capture the history of colonialism, modernism, anarchism and much more in its glittering net.

-

Joy Lawn, regular reviewer of YA fiction

The finest YA novels I have read this year are Australian. Three are YA debuts. Two are speculative, genre-bending and prescient while two are #ownvoices stories of cultural minority groups. The End of the World is Bigger Than Love, by Davina Bell, is an audacious yet brilliantly balanced and sustained tale set on a remote island in an almost recognisable future.

The internet is obsolete and a pandemic is rife. Twins Summer and Winter have conflicting reactions to bear-like Edward. A bear is also a companion in Gina Inverarity’s Snow. Snow is a reimagining of Snow White set in a post-climate-change world. Told in a timeless style, it features an eponymous heroine who trusts and treasures the natural world. Tribal Lores, by Archimede Fusillo, and The F Team, by Rawah Arja, share rich family heritages — Italian Catholic and Lebanese Muslim respectively — through gripping insights into young men in working class suburbs. Fusillo achieves the extraordinary feat of revealing the fragility behind the bravado of young men who straddle two cultures. Arja writes for those who feel marginalised. Her authentic, charismatic, sometimes hilarious, characters are a rallying cry for visibility, understanding and respect.

-

Stephen Loosley, author and critic

It has been an outstanding year for cloak and dagger, beginning with Peter Edwards’ perceptive biography of the godfather of Australian spies, Justice Robert Hope. Law, Politics and Intelligence: A Life of Robert Hope is exhaustive and persuasive. On the global stage, Putin’s People: How the KGB Took Back Russia and Then Took On the West, by Catherine Belton, charts the astonishing rise of a humble KGB officer, Vladimir Putin, who never appears to have left the Lubyanka, from Dresden through Saint Petersburg to Moscow. Agent Sonya: Lover, Mother, Soldier, Spy, by Ben Macintyre, does not disappoint. It is a tale of a GRU colonel, who began political life in the pre-war German Communist Party and finished as an unassuming middle class woman cycling in Oxfordshire, passing the West’s atomic secrets to the Soviets.

Politically, the US has dominated, and Bob Woodward’s Rage set the standard, accompanied by a brilliant satire on the Trump administration by Christopher Buckley, Make Russia Great Again. Chris Wallace, in How to Win an Election, is aspirational and optimistic about Australia, while Volker Ullrich registers the calamitous end of a despot in Hitler: Downfall 1939-1945. First class efforts in crime writing include Michael Connelly, The Law of Innocence, and Don Winslow’s book of short stories Broken. Michael Robotham excelled internationally with Good Girl, Bad Girl.

-

Alex Miller, author

My picks are Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste: The Lies That Divide Us, and Billy Griffiths’ Deep Time Dreaming: Uncovering Ancient Australia. The greatness of these books lies in their unmasking of the inherently racist evils of hierarchical thinking about humanity. Griffiths undermines and collapses the hierarchical assumption that has informed works of history for generations when he challenges the claim that “‘progress’ – articulated as the move from foragers to farmers” represents a step up from a lower rung on the “ladder climbing upwards towards the ultimate destination of agriculture and industry” and reminds us “that there is no inherent value to a farming or a foraging way of life”.

Griffith’s argument lays bare the “colonial assumptions about evolutionary hierarchies” and claims respect for our common humanity as the basis of civilised thinking. After Griffiths, human history can never again be written as if it represents some kind of ladder of perfection. Wilkerson’s powerful unmasking of the American lie that it is the land of the free is essential reading. She illustrates the black/white basis of the lie when she tells of the young woman from Africa who told her, “You know, in Africa there are no black people ... They have to go to England or America to find out that they are black. In Africa there are just people.” The enabling of racism through hierarchy is the underlying enemy for Wilkerson too.

-

P aul Monk, author and critic

This year has been notable for the COVID-19 pandemic, Donald Trump’s electoral circus and the sharp deterioration in our relationship with China. Richard Horton, editor in chief of The Lancet, gave us The COVID-19 Catastrophe, an invaluable guide for the perplexed. Brittany Kaiser’s Targeted, Richard Stengel’s Information Wars, and Julia Ebner’s Going Dark were all good on the epistemological and political challenges of social media.

John Bolton’s The Room Where It Happened, Rick Wilson’s Running Against the Devil, and Neal Katyal’s Impeach: The Case Against Donald Trump were very rewarding and thought-provoking on the Trump challenge. But the book that scoops the pool in 2020, as far as American politics goes, has to be the first volume of Barack Obama’s presidential memoir A Promised Land. It was well worth waiting for.

Several other books, on diverse subjects, rated very high on my reading list this year: Tom Mueller’s Crisis of Conscience: Whistleblowing in the Age of Fraud; Brian Greene’s Until the End of Time; Daniel Chirot’s You Say You Want a Revolution?; and Sam Dagher’s Assad Or We Burn the Country. It’s so good to be spoiled for uncensored choice. It’s so rewarding to be a reader of (good) books.

-

Thuy On, poet and critic

It’s rare that a debut novel is so brazenly confident it swaggers but Vivian Pham’s The Coconut Children is one such book. Set in Cabramatta in the late 1990s, it’s an impressive synthesis of place and character, and the dialogue and set pieces between teenage sweethearts Sonny Vuong and Vincent Tran crackle with energy. In this pocket of western Sydney beset with poverty and its concomitant bedfellows, crime and violence, Pham draws deep from her own experiences, but the book is also adorned with poetic flourishes and irradiated with humour and warmth. Full of colour and detail and written with the bravura of adolescence that young Pham herself has barely left behind, The Coconut Children marks a new literary talent.

Great books have the power to change your thinking and so it was with Dutch historian Rutger Bregman’s Humankind. As a lifelong cynic, liable to believe in humanity’s predilection towards bin-fire polemics, I was nonetheless persuaded by Bregman’s reasoning and a raft of evidence throughout the ages that as a species we lean towards altruism. It’s an optimistic and reassuring read, particularly in the year that was 2020.

-

Felicity Plunkett,

poet and critic

The ‘‘gloriously winged / Angel’’ sweeping through Rowan Ricardo Phillips’ poetry collection Living Weapon might seem far from the fey uplifters who populate Ali Smith’s seasonal quartet, but the two works — Smith’s latest is Summer — celebrate the imagination and the angelic, variously defined. Phillips’ poetry balances a literary treasury with a catalogue of violence in celebration of resilience and creativity, as does the gloriously virtuosic Summer.

In The White Book, Han Kang wraps a splintery meditation on white around the evocation of a woman alone, delivering her stillborn premature baby. The effect is ‘‘white ointment applied to a swelling, like gauze laid over a wound’’. Fleeting and fragile life is the overarching theme of this lyrical work of consolation. Josephine Rowe’s On Beverley Farmer is luminous, wise and sustaining. Favourite Australian fiction includes Mirandi Riwoe’s Stone Sky Gold Mountain, Amanda Lohrey’s The Labyrinth and James Bradley’s Ghost Species, exploring in fiction the questions of Anthropocene loss and recuperation his also-brilliant nonfiction returns to. Works by Andrew Pippos (Lucky’s), Laura Elvery (Ordinary Matter) and Paul Dalgarno (Poly), dipped into with delight, await.

-

Mandy Sayer, writer and critic

This year I found solace in reading biographies, appreciating the many arcs and dips of a single, distinguished life — and how the art of biography can be further heightened through an original narrative voice and structure. The highlights were Ma’am Darling, by Craig Brown, an impressionistic and hilarious account of the life of Princess Margaret, told through a series of 99 anecdotes from a multitude of sources. Meg Stewart’s Autobiography of My Mother is a vivid account of the life of Australian painter, Margaret Coen, narrated in the first-person, as Stewart brilliantly ventriloquises her mother’s storytelling style. Conversely, in Daddy Cool, biographer Darlene Bungey inserts herself as a character into a story about a daughter trying to unravel the many secrets and scandals of her father’s past.

A more traditional offering came in the form of A Life of Barbara Stanwyck: Steel-True 1907-1940, by Victoria Wilson, a highly-researched study of a streetwise orphan who grew up to become one of Hollywood’s most disciplined and accomplished actors. In 2007, when American poet John Ashberry was asked where he turned to for consolation, he replied, “Probably to a movie, something with Barbara Stanwyck.”

-

Beejay Silcox, writer and critic

The last book I read before COVID drew a line across my life was Vicki Hastrich’s Night Fishing: Stingrays, Goya and the Singular Life. Unwittingly, it was the perfect primer for what was to come: an ode to quiet contentment.

Returning to a beloved stretch of Aussie coastline — the place her family holidayed when she was a child — Hastrich finds her sense of awe undimmed. But now she has a language for what she sees and feels, names for all the creatures. Her memoir is a literary rockpool, a little cavern of magic. I felt the same sense of wonderment reading Susanna Clarke’s new novel, Piranesi, the tale of a grand, crumbling house whose endless halls imprison an ocean. Perhaps the greatest pleasure of work as a critic is being up-ended by a book you would never have picked up otherwise. Piranesi’s captive tides swept me up this year.

-

Diane Stubbings, writer and critic

For me, the fiction highlight of 2020 was Emma Donoghue’s The Pull of the Stars. Set in Dublin during the 1918 pandemic, and featuring characters who might have walked straight out of a play by Sean O’Casey, it managed to transform a litany of death and despair into a powerful expression of hope. Close behind was Richard Flanagan’s The Living Sea of Waking Dreams, a passionate and evocative study of what it means to live and, more importantly, what it means to die. I loved the generosity of Clive James’ poetry anthology The Fire of Joy, and the intelligence of Olivia Laing’s essay collection, Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency. And I was intrigued by two timely allegorical novels: Don DeLillo’s The Silence, and M. John Harrison’s The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again.

The book I couldn’t put down was Woody Allen’s autobiography Apropos of Nothing. Although slightly overbalanced by his lengthy, but persuasive, defence against abuse allegations, it was nevertheless a fascinating narrative of his career as a writer, comedian and filmmaker, and, in his account of his breakthrough years, a brilliant paean to the craft of writing. There’s also the wonderful revelation that the man Allen most envies is Tennessee Williams — because it was Williams who got to write A Streetcar Named Desire.

-

Louise Swinn, writer and critic

Broadcaster Jacinta Parsons shows herself to be a gifted writer in Unseen, a gripping account of life with chronic illness, written with pathos and expansive humour. Her empathy makes her a warm, candid storyteller, and this is a very affecting story. I was happy that Maggie O’Farrell’s Hamnet won this year’s Women’s Prize for Fiction. It is a reimagining of the life of Shakespeare’s son who died aged 11, and it tells Hamnet’s mother Agnes’s story, as well as showing the way Shakespeare poured the grief and tragedy of his life into his art. O’Farrell is a truly transporting writer.

Fire Flood Plague, edited by Sophie Cunningham, is a collection of essays from many of Australia’s sharpest writers, wrestling with climate catastrophe, politics and personal calamity during a year of environmental chaos. It’s an expertly constructed document of an unforgettable year, with perspectives that remind us how best to live.

Kiley Reid’s Such a Fun Age is an impressive debut novel. It’s a funny but also quietly devastating satire, shining a light on very contemporary characteristics, dealing with significant current issues, and doing so through truly engaging characters. Such a fun book — but also incredibly incisive.

-

Karen Viggers, novelist and critic

For me, 2020 has been a rich one for books, especially with the increased reading time made available by COVID-19 restrictions. Several books moved, taught or uplifted me. Max Porter’s Lanny is short but laden with character, place, myth and refreshing experimental writing. How to be an Artist by Jerry Saltz led me back to writing during tough lockdown times. And Felicity Volk’s Desire Lines redefined the word beautiful in terms of prose, landscape and love story.

However, the book that rocked my foundations this year was Sofie Laguna’s novel, Infinite Splendours, the story of Lawrence, a sensitive 10-year-old boy, damaged by trauma, who finds meaning and solace in art.

This book is at times sad, stressful and devastating, but also intimate and moving with touches of unexpected humour. Nobody inhabits the headspace of character as well as Laguna. In her tender but unflinching style, Laguna explores the far-reaching impacts of childhood trauma, and delves into the elusive concept of how art is born within the artist. Through Lawrence and his experiences, she digs deep into sources of inspiration, the exploration of ideas through art, and those rare fleeting moments when an artist comes close to understanding life through creativity.

-

Robyn Walton, writer and critic

In fiction, I admired Kevin Barry’s inventive use of language and literary modes in Night Boat to Tangier. Barry gives us a touchingly co-dependent pair of washed-up Irish gangsters bantering with each other, remembering, waiting. It’s prose, poetry and performance script all in one. John Connolly is another Irish writer with a love of language, in his case at the more ornate and mannered end of the spectrum. When Connolly brings his skills to bear on grubby scenarios — most recently in The Dirty South — he makes something different of the crime genre.

In Australian-authored crime fiction I was most impressed by Natalie Conyer’s debut novel, Present Tense. With its action taking place in the complex, volatile and politicised society of Cape Town, where Conyer grew up, this is a police procedural that’s engaging on a number of levels.

-

Geordie Williamson, The Australian’s chief literary critic

M. John Harrison is best known as the author of the finest rock-climbing novel ever penned (Climbers, 1989), and as a central figure in British Science Fiction since the late 1960s. Though anyone who has read his genre works will know that they are as austere, formally experimental and sardonically self-aware as any strictly literary fiction being published today.

The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again, Harrison’s latest novel, also eludes pigeonholing. It is a ghost story of sorts, set between London and Shropshire. It combines strange internet conspiracies about a new species — literally, little green men — Charles Kingsley’s The Water Babies, and real people who disappear inexplicably into shallow ponds.

A tale of mystery, then, filled with uncanny moments and weird recurring tableaus. But it is also a state of the nation novel, albeit a nation seemingly in the grip of a bad acid trip. What ties these disparate strands is Harrison’s prose, micrometrically alert to the outer environment of 21st century England, as well as the psychological inscapes of his perplexed and perplexing characters. Author China Mieville considers it a scandal that Harrison hasn’t won the Nobel. That a book this good should pass with such scant notice in this country is another.

-

Gerard Windsor, author and critic

Publisher Everyman has been doing quality retrieval work. In 2019 they published Elizabeth Bowen’s Collected Stories. You don’t find the compassionate wisdom of Anton Chekhov or William Trevor, but the imaginativeness! The word juvenilia is redundant; the sophistication of the stories she wrote when she was 19!

I finally embarked on Vasily Hoffman’s Life and Fate. Yes, it’s an epic Russian masterpiece. But War and War this time — Russians against Germans, the Soviet state against its own citizens. The range of the piercing vignettes is extraordinary. Two strangers seduce one another over a meal — an unhurried variant on Albert Finney and Diane Cilento’s frenzied scene in Tom Jones. And then, and then, 18 harrowing, well-nigh unbearable pages from the opening of the cattle wagons to the final breath in the gas chamber. Read it, everyone.

By way of respite I went to Robert Dessaix’s The Time of Our Lives. Growing up (or not), growing old, dying. Dessaix is ruthless, with himself and his readers. You blench, you laugh, you think hard. As time goes by we need, he argues, conversation and a finely tuned inner life to be intimate with. He’s practised this out loud in all his books.

-

Clare Wright, historian and author

Many of my standout reading experiences of 2020 could be corralled as Revenge of the Literary Nerds. In The Dictionary of Lost Words, Pip Williams has geeky fun with the origins of the English linguistic canon, having her heroine playfully but pointedly ask the question: how would we understand the world if women curated the Oxford Dictionary? Throw in suffragettes, a world war and the British class system, and this historical novel is a delectable treat for word nerds. American writer Sara Sligar gives us an archivist as central protagonist in her stylish and compulsive thriller, Take Me Apart. Can the meticulous, monotonous act of cataloguing a dead woman’s papers become fatal? Research addicts will recognise the apprehension.

I never thought I’d get through, let along enjoy, a book about boxing, but Stephanie Convery has delivered a knockout read with After the Count, a fascinating blend of investigative journalism and memoir which dissects the brutal intersection between law, medicine, sport, gender and the culture of violence. Not so niche after all. Finally, Australian writers divulge their creature crushes in Leah Kaminsky and Meg Keneally’s edited anthology, Animals Make Us Human. A post-bushfire fundraiser for Australian wildlife, this collection of stories and photographs by a truly spectacular line-up of authors will appeal to nature aficionados young and old. (And keep an eye out for #literarycritters, a guerrilla group of crafters making knitted replicas of the animals featured in each story!)

-

Ed Wright, writer, poet and critic

The dystopian seems to be everywhere as we exchange dreams of social progress for those of a ruined future. However, there are many ways to ruin the future. Margaret Atwood’s classic The Handmaid’s Tale and its sequel The Testaments attest to the dangers and inevitable hypocrisies of moral extremism. Wise, witty and immaculately constructed, they’re superb. In poetry I liked Anne Carson’s 2001, The Beauty of the Husband, a stunning exploration of an unwise marriage framed by epithets from British Romantic poet John Keats. Jaya Savige’s Change Machine dazzled with its surprising turns and breadth of reference. I enjoyed Richard Anderson’s Small Mercies, Bryan Walpert’s Late Sonata and Philip Salom’s The Returns for their insights into the challenges of maturity. Elizabeth Tan’s short story collection, Smart Ovens for Lonely People, with its voyages into the anomie of the internet age, was the most original book I read this year.

Being a year that at least created some downtime for literary meandering, I found myself absorbed and curiously repelled by Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther. Gabriel Bergmoser’s The Hunted kept me awake until 4am because I simply couldn’t put it down.

-

Susan Wyndham, author, journalist and critic

Three works of nonfiction nourished me this strange year with their intersecting wisdom and fine writing. Julia Baird’s Phosphorescense mixes memoir, scholarly research and sensual responses into a study of nature and human nature. Turn outward, pay attention, she says, and find pleasure in impermanence, imperfection, friendship, dancing, silence, oceans, children and dogs. A favourite line: “Cuttlefish changed my life in quiet ways.” The Gifts of Reading: Essays on the joys of reading, giving and receiving books, curated by Jennie Orchard, has passionate personal stories and reading recommendations from writers such as Robert Macfarlane, William Boyd, Roddy Doyle, Jan Morris, Max Porter, Alice Pung, Sally Vickers and Markus Zusak. As a bonus, sales of the anthology support the global literacy organisation Room to Read.

The Time of Our Lives, by Robert Dessaix, applies his wit and erudition to ageing with grace and a wink of naughtiness. Contentment comes from a rich inner life, he writes, and Andre Gide’s advice: “Desire only what comes to you, desire only what you have.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout