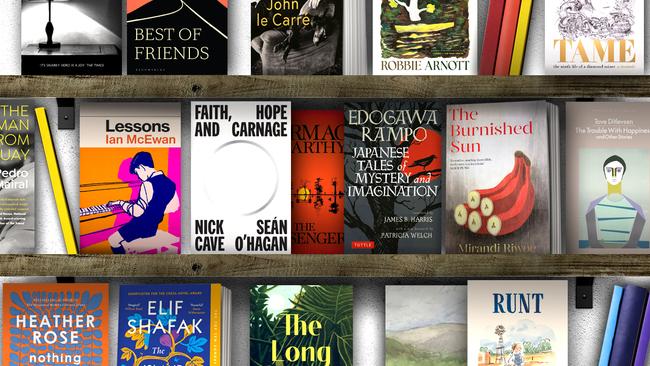

The Australian’s reviewers reveal their best books of 2022

Consider this your ultimate reading guide, where our reviewers reveal the books that moved, shaped, delighted and inspired them in 2022. How many have you read?

Welcome to our Books of the Year, where our critics reveal the books that moved, shaped, delighted and inspired them in 2022.

Caroline Overington, literary editor of The Australian

My favourite read was Sarah Holland-Batt’s The Jaguar (UQP) which is our Book of the Year. It’s a collection of poems about the death of Holland-Batt’s father, and the language is absolutely sublime.

In no particular order, I also adored:

Human Looking (Giramondo)

by Andy Jackson

Oh, this was astonishing. It’s a collection of poems about disability. Jackson himself has Marfan syndrome, which affects the skeleton, and a person’s appearance. Jackson constructs one poem from text from his own childhood medical file. Another is about parents who have to decide to keep their profoundly disabled daughter artificially small, so she will be easier to manage as she gets older. Another is about 19 patients killed in a “disability hospital” fire in Japan. Another is about people who become amputees by choice. This is … well, I said it already, it’s astonishing.

Patting The Shark (Penguin)

by Tim Baker

An award-winning surfing writer confronts stage four cancer, and the loss of his virility. He so loves his wife. He had loved being her lover. And that has been taken from him. An important conversation, by a marvellous wordsmith.

The Ninth Life of a Diamond Miner (Pan Macmillan)

by Grace Tame

This was unexpected. Tame was sexually abused as a schoolgirl and I guess I was bunkered down for a grim but necessary read. But Tame’s book isn’t anything like that. Her tone is warm. She is smart. There are surprises on every page. This is a bright, brilliant young woman, telling her story her way.

Faith, Hope and Carnage (Text)

by Nick Cave and Sean O’Hagan

This book presented in question-and-answer format, with trust between the two men, who are old friends, building as they approach the impossibly difficult topic of the death of Cave’s 15-year-old son, Arthur. Cave’s description of the physicality of grief – his panicked, vibrating heart – is mesmerising.

The Disappearance of Josef Mengele (Verso)

by Olivier Guez (translated by Georgia de Chamberet.)

What became of one of the world’s most evil men? He lived out his days paranoid, lonely and bunkered down, surrounded by wild dogs, broke, suspicious, hounded, in misery. Which is good. This book is based on the historical record, giving it real muscle.

Words for Lucy(Thames & Hudson)

by Marion Halligan

A poet writes about the life and premature death of her daughter, who perhaps shouldn’t have survived birth. But she did, and what a gift she was to those who came to know her.

A Message From Ukraine (Penguin UK)

by Volodymyr Zelensky

A little hardback, you’ll probably find this near the front of the bookshop. It’s a collection of Volodymyr Zelensky’s speeches, and you should buy it, not only because the words are beautiful – “We are all here” – but because a portion of the proceeds will go to Ukraine.

-

Geordie Williamson, chief literary critic at The Australian

In Fiona McFarlane’s new novel – a poised, subtle and ferociously intelligent reworking of that perennial Australian tale of the lost child – the author gives an old story new life. The Sun Walks Down (A&U) begins as a photorealist recreation of Colonial era outback South Australia but concludes as a visionary poem of place and a stern indictment of White Australia’s still-unsettled relationship to this continent.

Rick Gekoski’s Darke trilogy, which concludes this year with After Darke (Hachette), is a masterpiece of negative catharsis. The novel’s antihero, Dr James Darke – a reclusive, misanthropic bibliophile, filled with general rancour towards the world – gives paradoxical pleasure by venting so biliously on our behalf. For readers weary of earnest piety and emotion easily bought.

If the thought of Trump 2024 gives you pause, the best novel about Trumpism has already been written. Alexander Maksik’s The Long Corner (Europa Editions), set largely in a writers’ colony on a tropical island, is a grim fable about the ways power can co-opt culture and even warp our sense of reality.

Finally, Phil Christman’s How to be Normal (Belt Publishing) might be regarded as the non-fiction pendant to Maksik’s novel. His essay collection brings a rare voice of sanity and decency to our current overheated debates over religion, gender, race and so on. Imagine George Orwell grew up in the American Midwest and you’ll have a sense of Christman’s mix of plain English and radical critique.

-

Antonella Gambotto-Burke, author and critic

When not reviewing, lecturing, home educating, recording my first album for Mama feat. Antonella or navigating the British publication of my own book, I found myself mesmerised by the writing of Tove Ditlevsen, a Danish writer who fatally overdosed on sleeping pills in 1976.

(Why is the work of so many female literary suicides so compelling? Discuss.)

The dreary title, The Trouble with Happiness and Other Stories, memorably dismal cover, and the author’s suicide did not suggest delight.

But then I started reading.

Deceptively simple, Ditlevsen’s sentences uncoiled, extending their tendrils throughout the text as they both altered the meaning and texture until the stories began to reverberate, continuing to pulse long after the last word had been read.

“The child of an old man, it occurred to her, as she remembered a phrase from some poem: born of tired loins,” she wrote. “Her own thought shocked her so much she was compelled to go and kneel in front of him, put his head in her hands, and observe his beautiful mouth and his tired eyes with the distant look in them, and his slim hands which could never be still, so were constantly fumbling with a pipe or cigarettes or searching for tobacco or change in all his pockets.”

In some ways, Ditlevsen is a miniaturist of her time but her worlds are, in fact, eternal. Rather than the overwhelmingly sad and beautiful half-life of the great Japanese modernists, the end effect is one of respect for the smallness of a human life, and in that, its preciousness.

I bow to her genius.

Antonella Gambotto-Burke‘s new book, Apple: Sex, Drugs, Motherhood and the Recovery of the Feminine, can be ordered online.

-

Stephen Romei, cultural critic, bon vivant, journalist, father and good friend of the Books pages

My best books: Cormac McCarthy’s The Passenger (Picador) and Stella Maris (Picador). This intimately connected pair, centred on a brother and sister who may be more intimate than the law allows, made me reconsider my life – but not for that reason!

Two other novels also made me dwell on the life I have chosen to live, the lives I have chosen not to live and the life ahead: Alex Miller’s A Brief Affair (Allen & Unwin) and Ian McEwan’s Lessons (Jonathan Cape), each of which explores paths taken and their untrod alternatives. Heather Rose’s Nothing Bad Ever Happens Here (Allen & Unwin) had the same life-questioning influence (I am of that age). This rocket of a book blasts through the Tasmanian author’s almost unbelievable life before she became the author of novels such as The Museum of Modern Love and Bruny. George Saunders’s Liberation Day (Bloomsbury) is an archly funny collection by the Booker Prize winner is a reminder that short fiction is where he’s at the peak of his powers.

For younger readers, Craig Silvey’s Runt (Allen & Unwin). This tale of a girl and a dog has something generous and wise in it for its target audience, their parents and grandparents.

Poetry: I’m in awe of Sarah Holland-Batt’s The Jaguar (UQP). In the poem My Father as a Giant Koi, the poet is with her dying father.

“He cannot trust the scratched headlamps/ of his eyes so he navigates by feel,/ angling his huge whiskered head/ mouth-first towards the fork, weaving/ like an adder charmed by smoke,/ then he bites down to find the world/ suddenly there again, solid as metal and bait.”

Each of these books made me think about my life. My book of the year convinced me to change my life. Faith, Hope and Carnage (Text Publishing) is a conversation between Australian rock star Nick Cave and Irish journalist Sean O’Hagan. I listened to an audiobook, narrated by the authors, and I recommend this approach. Hearing Cave speak is more personal than printed words on a page. He talks openly about everything, from his past heroin addiction to his present obsession with making ceramic models. Fans of his musical career will laugh as he talks, with a lot of love and a little fear, about his bandmates past and present. Yet this is not a rock ’n’ roll book. The 2015 death of Cave’s 15-year-old son Arthur is at its heart, as it is at Cave’s and his wife Susie’s. When he opens up about the sense of responsibility he feels it is heartbreaking. It’s not a matter of blame. It’s a matter of doubt. After listening to this book I bought a hardback copy. I will carry it as a sort of personal bible for the journey still to come.

-

Diane Stubbings, writer and critic

Two perennial Nobel-prize contenders proved they are still at the top of their game. Jon Fosse’s Septology (Giramondo) is a mesmerising novel about one man’s encounter with another version of himself. A daring and original examination of what it means to live, Fosse’s prose comes at you like gentle waves, but the impression it leaves is profound.

In The Singularities (Alfred A. Knopf) John Banville brings the themes and characters of some of his earlier novels to a thrilling culmination. Set in an alternate reality, Banville – his language exquisite – plays with ideas of time and space, the layering of past, present and future forcing us to question whether we can ever truly know what is real.

Irish writer Sara Baume’s Seven Steeples (Tramp Press) is a beautiful portrait of a young couple as their lives begin to map the rhythms of the natural world. Her writing is subtle and elegant, and she deserves a wider audience.

In The Ninth Life of a Diamond Miner (Macmillan), Grace Tame demonstrates that she’s not just a courageous and inspiring young woman, she’s also a stylish writer. She’s written an important book – one that both augments our understanding of what it means to be subjected to sexual abuse, and gives hope and strength to other survivors.

Finally, Marion Stell’s The Bodyline Fix (UQP) about the first women’s test cricket series between Australia and England, is a hugely enjoyable tale of plucky women having a grand and groundbreaking adventure, a story that’s begging to be dramatised.

-

Thuy On, writer and critic

With his third book, Limberlost (Text), Robbie Arnott cements his reputation as one of Australia’s most affecting storytellers. Unlike his previous efforts that skilfully braided mystical elements into its narrative, Limberlost is more grounded in realism but is no less powerful. It’s the tale of Ned whose life – from childhood to adulthood – is canvassed with Arnott’s sensitive eye. It’s the 1940s. Ned grows up on an orchard in Tasmania with his emotionally damaged father and taciturn sister. His brothers have been enlisted into war, and Ned himself is hunting rabbits to be turned into slouch hats for soldiers. What he’s really saving for, however, is a boat of his own. This simple premise is slowly expanded upon as Arnott uses the colours and creatures of the natural world to populate Ned’s world.

Mirandi Riwoe’s The Burnished Sun (UQP) is a collection of stories that brings to the fore the inner lives of women otherwise marginalised. She bathes Annah, one of Paul Gaugin’s models, in new light against the grimness of 19th century Paris and recasts the tale of a throwaway character in a Somerset Maugham short story, to tragic effect. The whole book is gifted with Riwoe’s characteristic sense for detail across wide ranging historical contexts.

Another collection of stories, and something completely different, is Chris Flynn’s Here be Leviathans (UQP). All bar one story is written from the perspective of a non-human entity, including a grizzly bear, a genetically altered platypus, a hotel room and an aeroplane seat. Initial worries that this technique is one-note gimmickry falls to the wayside as Flynn’s humour. dialogue and imagination fires up an experimental brew of pure wonder (remember he has form – his previous book, Mammoth, was narrated by a fossil). In Sarah Holland-Batt’s The Jaguar (UQP), the poet confronts her father’s illness and death with unflinching regard. In this eulogy, her words about decay and mortality are shot through with a lyric intensity as beautiful and ferocious as the titular beast.

Thuy On’s latest book is Decadence (UWAP)

-

Gideon Haigh, writer and critic

As the years pass, I grow less interested in the front window of Readings, and more absorbed in the darker recesses of Abebooks, so the best books I read in 2022 were mainly old. None was better than a 1956 collection of wonderfully dark short stories by Edogawa Rampo, Japanese Tales of Mystery & Imagination (Tuttle Shokai; translated by James B. Harris): think an orientalised Edgar Allan Poe crossed with Arthur Conan Doyle and Wilkie Collins. It starts with the tale of a man who has himself sealed in a chair in order to be closer to the object of his infatuation, and from there gets only weirder.

Re-reading Journey’s End sent me in pursuit of R. C. Sherriff’s The Fortnight in September, first published in 1931, and recently reprinted (Scribner). It’s the story of a family’s annual holiday in Bognor, with the author eavesdropping on all their hopes, disappointments, resolutions and resignations. It’s a heartwarming, intimate and humane novel: Ishiguro thought that “the beautiful dignity to be found in everyday living has rarely been captured more delicately”.

My favourite new novel was Pedro Marial’s deft and intriguing The Woman from Uruguay (Bloomsbury, translated by Jennifer Croft). Also recommended is Brian Dillon’s Essayism, a lively sharp-edged contemplation of the form, in history and in the writer’s life, with fresh perspectives on Woolf, Perec, Didion and Sontag. And I admired Chip Le Grand’s Lockdown (Monash University Publishing), an even-handed retelling of Dan Andrews’ bizarre social experiment.

-

Peter Craven, cultural critic

Les Murray’s Continuous Creation: Last Poems (Black Inc) shows the work of the most talented poet in Australian history and Charmian Clift’s Sneaky Little Revolutions (NewSouth) the work of our most sparkling essayist.

You don’t have to be a royal family tragic to find Tina Brown’s The Palace Papers (Random House UK) riveting even though she’s better on Diana and Charles and Camilla than she is on the younger members of the family. But what timing!

If you want a subtle and readable depiction of two Pakistani women, highly successful in London, who have known each other forever try Best of Friends (Kamila Shamsie, Circus) about the tragicomic nature of friendship which has a bewitching Jekyll/Hyde aspect.

Robert Crawford’s Eliot After The Wasteland (FSG) is a portrait of how the great poet promised marriage to a woman he couldn’t on religious grounds marry only to discover on the unexpected death of his first mentally ill wife that he could not face sex at all. Eliot remains utterly sympathetic through this wilderness of paradoxes – and then, astoundingly, the story ends happily.

A Private Spy: The Letters of John le Carre 1945-2020 (Penguin) is also thrilling in its confessionalism and has a marvellous juggling histrionic quality. It’s a collection full of warmth and contradiction which has the reader trying to keep up with the dark glass of le Carre’s introspection and bravura.

Robert Harris is another trashmeister who wants to flatter the highbrow inside the lover of ripping yarns. In Act of Oblivion (Penguin) we’re off with the runaway regicides of Charles I who had escaped to America. Harris is brilliant at sustaining a dual sense of truth and adventure.

With Cormac McCarthy’s two new books –The Passenger and Stella Maris (Picador) they’re parts of the one story – we get a supreme master of fiction luring us into clouds of unknowing and dark abysses. The books are riddling both in their narrative technique and in their endless discussion of mathematics and physics. Do they work? They’re at such a far extremity of literary elevation that their very obscurity seems the signature of their grandeur. Like Milton, like Joyce, like God knows what.

-

Stephen Loosley, Senior Fellow at the United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney

A visit, post-Covid, to a favourite bookstore, Heywood Hill in Curzon St in London, yields quite marvellous gems. The first is Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli (Simon & Schuster) by Mark Seal which is a highly engaging account of the making – now 50 years ago – of The Godfather by Francis Ford Coppola.

In Stalin’s Library: A Dictator and His Books (Yale University Press), Geoffrey Roberts explores the Soviet dictator’s wide taste in reading, and in so doing, shines a light into his intellectual curiosities.

Alex Joske has written a superb account of Chinese espionage, entitled Spies and Lies: How China’s Greatest Covert Operations Fooled the World (Hardie Grant).Joske works at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute in Canberra, where I am a Senior Fellow. This book is revelatory, marrying influence with espionage.

Niki Savva’s Bulldozed (Scribe) should be under every thinking Australian’s Christmas tree. It is raw-edged and remorseless in its assessment of the collapse of the Morrison government, courtesy largely of its leader, and the handing of the keys of the Lodge to Anthony Albanese.

Internationally, Harald Jahner’s Aftermath: Life in the Fallout of the Third Reich, 1945-1955 (Penguin) is a ground-breaking account of how West Germany emerged from the ruins of Hitler’s Third Reich and became a very significant European and global player.

Presidentially, Harry Truman’s reputation is confirmed by Jeffrey Frank’s The Trials of Harry S. Truman: The Extraordinary Presidency of An Ordinary Man, 1945-1953 (Simon & Schuster). The Jazz Age President: Defending Warren G. Harding (Regnery History) by Ryan S. Walters should cause some reconsideration of the 29th President’s usual rating as America’s worst.

The best reading for 2022, however, was an American classic in Willa Cather’s 1927 novel Death Comes for the Archbishop (Penguin). Set in Spanish North America prior to the absorption of the South Western territories by the United States, it is a convincing novel in its originality. The narrative is centred on the Catholic Church in the New World: the clergy; the Native Americans and the European faithful. Willa Cather deserves greater recognition, well beyond the orbit of Red Cloud, Nebraska.

-

Victoria Grieve Williams, Australian historian and Warraimaay woman from the mid north coast of NSW

Professor Margaret D. Jacobs fearlessly documents the violent takeover of America’s Native lands in One Hundred Winters: In Search of Reconciliation on America’s Stolen Lands (Princeton University Press). The history is shocking and astounding in the extreme. She reflects the consciousness of many settler and immigrant peoples who now wish to deal with this founding history in appropriate ways. Jacobs canvasses various approaches, including Australian initiatives. She is working with Americans who find ways to make amends, without waiting for formal government initiatives, with surprising outcomes.

In South to Freedom: Runaway Slaves to Mexico and the Road to the Civil War (Basic Books), Alice M. Baumgartner reveals the history of the tense relationship of the USA with the peoples south of the border where slavery was outlawed in 1837 and fugitive slaves were given sanctuary. The American settlers insistence on retaining and expanding the human trade into Mexican territories has been foundational in the fraught relationship with Mexico from then until after the Civil War. This is a powerfully documented and well-written history that reads like an unravelling drama – great read.

The Island of Missing Trees (Viking) by Elif Shafak is wonderful. Widely acclaimed as even better than her last triumph, Ten Minutes 38 Seconds in This Troubled World, this book confirms Shafak as a master of translating the emotion of human connection to a wide audience. The richness and depth of her human stories about the impacts of borders, classism and racism is breathtaking. In this novel she has a new take on star-crossed lovers, a transnational story in which she makes the movement of history and coincidence, intuition, love and despair simply magical.

All the best books on my list so far have been written by women – and here is one written by a woman about a woman writer and both of them Australian. Shirley Hazzard: A Writing Life (Virago) is by Brigitta Olubas, a professor of literature who has researched the writings of Australian expatriate writer Shirley Hazzard, and more recently researched and meticulously documented her transnational life. An extraordinary woman, Hazzard was brave, opinionated, forthright, canny and powerful. She created a salon that was rich with talent, reflecting her own. This book surprises and delights with amazing vignettes of her encounters with a host of public figures and even more writers, including Margaret Mead, Patrick White, Murray Bail, Saul Bellow, Sumner Locke Elliot. She was privileged and a sophisticated citizen of the world but reminded us – “Australia is not an innocent country. This nation’s short recorded history is shadowed, into the present day, by the fate of its native peoples …”

The White Earth Anishinabe poet Gordon Henry takes us into another country entirely in Spirit Matters: White Clay, Red Exits, Distant Others (Holy Cow Press). This is an uncanny encounter with lives and times too precious to disremember and a poetic voice that haunts the present. I enjoyed this beautiful reflection on the spirit and the movement of life and times immensely.

-

Ross Fitzgerald, emeritus professor of history and politics at Griffith University

My favourite book for 2022 is Grainne Cleary’s Why Do Birds Do That? (Allen & Unwin). If readers wonder why birds in Australia behave as they do, and what are their peculiar habits, the answers are to be found in this beautifully produced paperback.

As a wildlife ecologist who promotes citizen involvement, Cleary argues that the ability of certain species, “including some that are threatened, to thrive in our gardens means that gardens help to support and maintain their needs”. Hence it is incumbent on Australians to make our gardens more wildlife friendly. It is important not just to know which birds frequent our gardens, but to maintain and improve the habitats that support them.

Another brilliant book, Mike Carlton’s The Scrap Iron Flotilla (William Heinemann Australia) tells the story of HMAS Vendetta, Vampire, Voyager, Stuart and Waterhen, which were sent by prime minister Robert Menzies to beef up the Royal Navy in the Mediterranean.

Josef Goebbels contemptuously referred to them as a “load of scrap iron”.’ But after the Nazis invaded Greece in April 1941, the five old destroyers rescued thousands of Allied troops. When the Italian “Desert Fox”, Erwin Rommel, held at bay 14,000 Australian soldiers, they ran “the Tobruk Ferry”, bringing supplies of food, medicine, and ammunition by night and rescuing wounded soldiers. Although only HMAS Vendetta survived World War Two, this tale of naval courage and endurance is inspiring.

A highlight of Philip Deery’s Spies and Sparrows: ASIO and the Cold War (Melbourne University Press) is the story of one of ASIO’s most effective agents. In 1951, suburban Adelaide housewife Anne Neill joined the Communist Party of Australia. While working diligently as a CPA member, Neil penned hundreds of security reports about her comrades and their activities. She was so dedicated that, when her handlers suggested she take a holiday, Neill responded, “No. Communists don’t take holidays!”

In 1952, after attending the World Peace Congress in Vienna as a CPA representative, she visited Moscow. Having an ASIO operative, “inside the belly of the beast”, was a considerable coup.

In November 1953, Neill attended Soviet National Day celebrations at the Russian embassy in Canberra. There she had private meetings with Vladimir Petrov, who a few months later defected with his wife Evdokia.

Although the timing raised suspicion among some comrades, Neil continued work as a seemingly loyal communist and a devoted ASIO agent. But in 1958, after the mother of a CPA committee member expressed suspicions that Neill was working undercover, her handlers pulled the plug. The confidant was a secret ASIO agent herself!

John Howard’s A Sense of Balance (Harper Collins) deserves a wide readership. It is fascinating to learn that Howard thought that “Labor made a huge blunder” in replacing Kevin Rudd with Julia Gillard. He also argues that no coherent policy case was advanced by Malcolm Turnbull as to why Tony Abbott should be deposed as Liberal leader and thus PM.

The day after the 2016 election, Howard attempted to persuade Turnbull to make Abbott defence minister. According to Howard, this would have given the country an energetic and articulate minister, “with a deep commitment to our defence personnel. It would also have kept Abbott within the tent”.

This book does gloss over the widespread perception that, after Turnbull replaced Abbott as PM in September 2015, the Liberal Party seemed to stand for nothing.

But the older he gets, the better John Howard is as a writer.

Ross Fitzgerald’s most recent publication is My Last Drink: 32 stories of recovering alcoholics, coedited with Neal Price (Connor Court).

-

Helen Elliott, writer and critic

Why isn’t the name Beth Spencer on every Australian reader’s lips? One guess is that she is an early and Antipodean version of Taylor Swift: too talented, impossible to categorise because she sings, does audio, writes across time, space, genres and possibly genders. Spencer’s analysis of the original Bewitched is a miracle of barbed wit. Her analysis of Barbie (doll) another. The cover of her latest collection of dazzling tales, The Age of Fibs (Spineless Wonders) uses the word microlit and maybe that says it all; lit from within and without with a fractured magic that has given me great pleasure, shouts of recognition and laughter before pushing me over a cliff into new thought and understanding of what it is to be female, to be simultaneously stupid and smart and trying to take a sounding of her life. Bravura writing. Bravura woman.

Ian McEwan has called this last novel, The Lessons (Penguin) a whole-life novel because it spans a male life, and those connected with him, from 1948 until the beginning of this year. I am not always a fan of the often humourless, super-British McEwan but this is tender provocation displaying a new generosity of spirit. Completely absorbing, and the writing, oh the writing is a lesson in itself. THIS is how to do it. And here’s a relationship, father and son that details the sweetest gift Feminism can give to a man.

Abdulrazak Gurnah won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2021. Gurnah, was born in Zanzibar but has been living and teaching in the UK since the 1960s. His last novel Afterlives (Bloomsbury) set in an unnamed city in Africa spans the first half of last century. The country is a German colony but the Africans, not the colonisers are the focus of this novel. Afterlives imagines the lives of complex people who have the same human yearnings as people everywhere but colonisation means they are largely unseen by the colonisers. One German martinet decides to teach his “boy”, the tender-hearted Hamza, to read Schiller as a sort of intricate emotional and intellectual trick. Some novels have the composure to make readers realign entire belief systems, to make their eyes fly open. I read with my hand over my mouth. A novel, a devastation as well as a revelation.

Elif Batuman’s name is on every reader’s lips. Deservedly so. Either/Or (Penguin/Cape) taken from Kierkegaard’s 1843 philosophical inquiry about how to live one’s life, hedonistically or responsibly, aesthetically or morally allows for Batuman’s ironic and comic voice to question everything. Set in Harvard in the 1990s when Selin, a super-bright 19-year-old Turkish-American woman tries to figure out her own messy and unnaturally innocent life with the help of Kierkegaard and a hundred other canonical writers. Innocent because she, a perfect idiot, thought that books, especially The Great Novels by men, had all the answers. As witty as all get out and as casually erudite as Lucille Ball.

-

Carmel Bird, writer and critic

The Queen of England died. As a result, I re-read Dennis Altman’s recent book God Save the Queen (Scribe). There is a subtitle: “The strange persistence of monarchies.” Many Australians are probably inclined to think Britain when they think monarchy, but the book explores in vivid and engaging detail the institution itself in kingdoms across the planet. As a declared republican, the author is finally not optimistic for a republican Australia any time soon, but reading this book could just change the minds of local monarchists.

Then the Queen of feminist publishing died. Carmen Callil founded Virago Press in 1973. This year I re-read her Oh Happy Day (Jonathan Cape). It was published around Christmas 2020, maybe not the best year for reading a passionate account of the horrors of British imperial rule. While being a kind of family history, it documents the purpose and the result of the British invasion of Australia in 1788. This was no “settlement”, but was “theft and dispossession and murder”. British society in the 1900s was a pyramid that moved from the monarch down through eight levels to the paupers at the vulnerable base. All is told in a style that lights up the scene, and the whole narrative is a persuasive, fierce, beguiling argument for social justice.

Working in unusual concert with Oh Happy Day is Gregory Day’s Words Are Eagles (Upswell) a collection of essays. This book documents the disruption of land and language caused by the British when they invaded the ancient country of the Indigenous peoples. Meditating on the tragedies enacted on the Wadawurrung lands where he has his “corner of the world”, the writer seeks a language that is the “speech of the earth”. The scope of this book is vast and glorious, the poetry of its prose sweet, soaring, and seductive.

This Devastating Fever (Ultimo) by Sophie Cunningham takes the reader back to the Britain of Leonard and Virginia Woolf. These characters literally haunt the Australian protagonist in 2020 as she struggles to write about them during a pandemic. This is a very moving novel, laced with wit, pathos, and ferocious truths. It too has a comment to make on the atrocities of colonialism, this time in Sri Lanka. As in Words Are Eagles, the natural world emerges as the place where hope is possible.

This list is compiled in conjuction with the nation’s publishers. Every year, writers will say: why didn’t you include my book! Sometimes it’s because we didn’t know about it. And because we can’t fit them all in. There are so many great books coming in 2023. We look forward to reviewing many of them. In the meantime, choose something to take on holiday. We’re almost there — Caroline Overington