The Australian genius who gave the whole world a fever

You might think Saturday Night Fever begins with John Travolta and ‘Stayin’ Alive’, or with Barry Gibb’s right hand. But where it really begins – and ends – is with Robert Stigwood.

Where does Saturday Night Fever begin?

Maybe with John Travolta and “Stayin’ Alive” – a deeply defiant, life-affirming song about living in New York City. Travolta struts down a Brooklyn boulevard, paint tin swinging in one hand, at one with the rhythm of the city and the song and the spheres. It’s a title sequence widely regarded as one of the greatest in cinema.

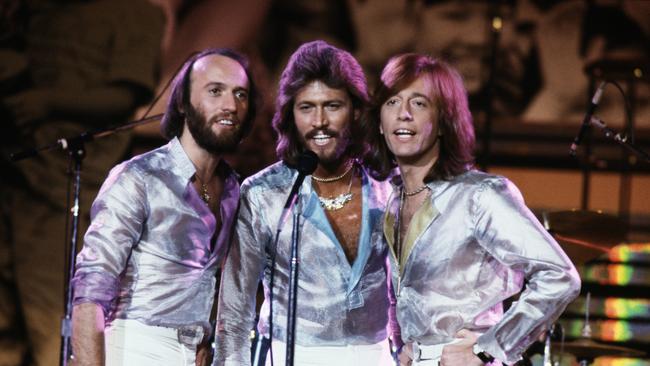

Maybe it starts with Barry Gibb’s right hand? The hand that always drove the Bee Gees. Even before he and his twin brothers Robin and Maurice began singing and harmonising, Barry had to first find the right groove on his guitar with its peculiar Hawaiian open-D tuning before they could do anything.

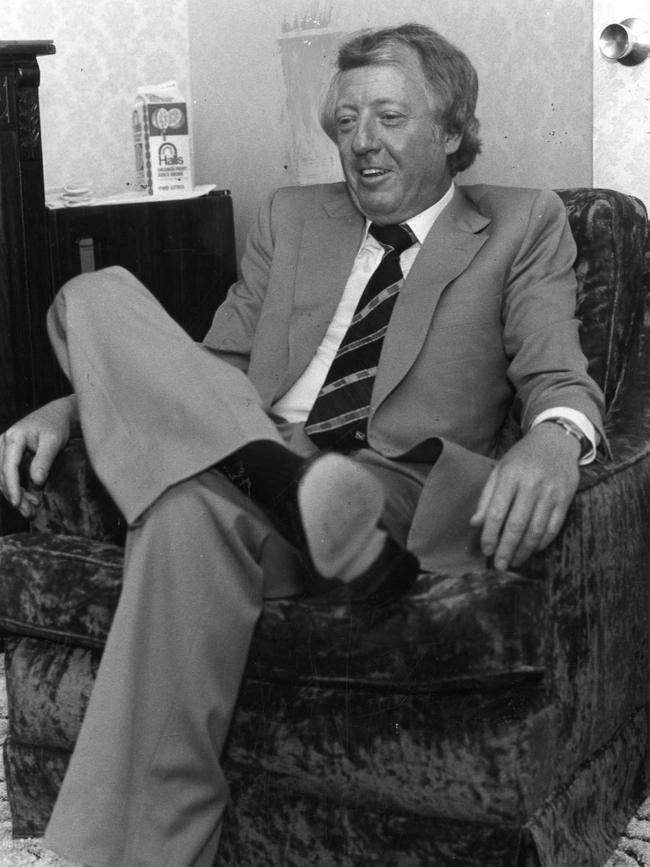

But where Saturday Night Fever really begins – and ends – is with Robert Stigwood. Stigwood was the expatriate Australian entrepreneur who was the Svengali/gay dad figure to the Bee Gees from the moment they arrived (back) in the UK at the start of 1967, who built a corporate structure around them and doted on them and was always looking for the exactly perfect film vehicle that would do for them what A Hard Day’s Night did for the Beatles.

Who took 10 years to find or create that vehicle, Saturday Night Fever, which would become one of the biggest film musicals and soundtrack albums of all time.

Well, one of the biggest-ever albums bar none, next to Grease, of course, which was the extraordinary other punch in Stigwood’s extraordinary one-two volley of punches in 1978 that amounted to what Newsweek magazine called “the hottest streak in the history of showbusiness.”

Saturday Night Fever was a masterpiece, certainly Robert Stigwood’s masterpiece, a great, great film/soundtrack that hijacked pre-punk pop to give definition to a generation lost in narcissism or diminishing expectations, depending on which of Christopher Lasch’s iconographic epithets you prefer – and it reinvented the Hollywood musical along the way.

Stigwood was the man who bridged the gulf between Hollywood and the music industry. Prior to him, Broadway producers, Hollywood studios and record companies all tended to regard each other with suspicion. It seems hard to imagine now, but back then they all thought the others were going to eat into their business. “Cross-promotion” was not a term in currency, let alone “synergy”. Stigwood changed that, and after him neither music or movies – nor the stage musical – would ever be the same again.

Modestly pitched by distributor Paramount’s PR as “a film that deals openly with the restless and explosive generation growing up in the 70s”, the critics loved Saturday Night Fever; and not just film critics but rock critics too. Audiences all around the world flocked to see it, and buy the records. In Australia, on Countdown every Sunday night, host Molly Meldrum was beside himself at the gumnut invasion of the American charts, Our Olivia, Our Bee Gees and Our Andy, all under the presiding spectre of “Mr Stigwood”, as Molly deferred to Our Quiet Giant.

But as soon as Saturday Night Fever seemed as overweening as all this, the backlash hit, and it set in. For the first three decades of Fever’s long, long tail, it got shot by both sides and demonised. On the left, its critics thought it was nothing but the corporate co-option of an underground subculture that belonged to a very gay/black caste in downtown Manhattan. On the right, rock-heads just thought “disco sucks”. “Death to disco” arose as a rally-cry as dumb and odious as the contemporaneous “Punk’s Not Dead”.

But the audiences never stopped dancing. Saturday Night Fever didn’t take disco to the suburbs, it was already there; it didn’t whitewash and straightwash disco, the scene in Brooklyn it so evocatively portrayed did so with all its racism, homophobia and misogyny. Social realism it’s called.

Fever was inexorable and the impact of Stigwood’s bold example was prompt. By the turn into the ’80s it was certainly established that never again would a blockbuster movie not have a soundtrack and that soundtrack keyed in to a marketing synergy, and/or vice versa. Much of a breaking wave spun directly out of Stigwood’s orbit: Grease co-producer Alan Carr’s car-crash Village People vehicle Can’t Stop the Music; John Travolta going on to a Fever for country music, Urban Cowboy, as if a counterpoint to RSO’s own new wave Fever, the now-cult Times Square; Olivia going on to the roller-disco Xanadu; and RSO also going on to handle the soundtrack for Fame, which finally yielded Hollywood-outsider Stiggy the Oscar he should have already snaffled for Superstar, Fever or Grease, or all three.

The Great Australian Camp tradition extended through the ’80s with film musicals including Starstruck, Shock Treatment, The Return of Captain Invincible, Young Einstein and even Sons of Steel, before the watershed of the ’90s and Priscilla, Muriel and Strictly Ballroom.

For the Bee Gees, Saturday Night Fever was both a blessing and a curse. But they outlived the hate, or at least the songs did.

For Robert Stigwood, after Times Square and 1981’s Gallipoli, which he co-produced with Rupert Murdoch, he got out of the game. Unlike so many in showbusiness, he knew when to fold ’em. He sailed off into the sunset, quite literally, aboard his yacht the Serina, and settled in the Caribbean island tax haven of Bermuda. He spent most of the ’80s having one big long lunch, before coming out of retirement in 1996 with his final salvo, Evita. It was fitting that Evita’s chief rival as the year’s best musical in ’96 was Romeo + Juliet, the second in what Baz Luhrmann called his Red Curtain Trilogy, in between Strictly Ballroom and Moulin Rouge. It was like the old master passing the baton on to the young apprentice.

I saw the solo Barry Gibb play live at Sydney’s old Entertainment Centre in 2013, and though by then both his twin brothers Maurice and Robin had died – and though his right hand was a little less driving due to arthritis, and his voice a bit creaky at the top of its falsetto – the show still had a lot of magic and that magic will probably never stop reverberating.

Stayin’ Alive turned out to be a self-fulfilling prophecy.

This is an edited extract from Soundtrack from Saturday Night Fever by Clinton Walker (Bloomsbury) out now.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout