Terry Smyth’s Australian Confederates: our rebels who fought on

Australian George Canning, serving on a Confederate ship, likely fired the last shot in the American Civil War.

The most intriguing trivia night question on the American Civil War is usually this. Q: What was the last battle of the Civil War, and who won? A: Palmetto Ranch, Texas. The Confederates won.

It is memorable because the battle was fought on May 12-13, 1865, well after Robert E. Lee had surrendered the main Confederate Army (of Northern Virginia) at Appomattox, Virginia, in April.

Now Australian journalist Terry Smyth adds a further dimension to the closing months of the Civil War in his lively book Australian Confederates.

Smyth’s argument is straightforward and persuasive. An Australian seafarer, George Canning, serving on the Confederate States ship Shenandoah, likely fired the last shot in the war on June 22, 1865.

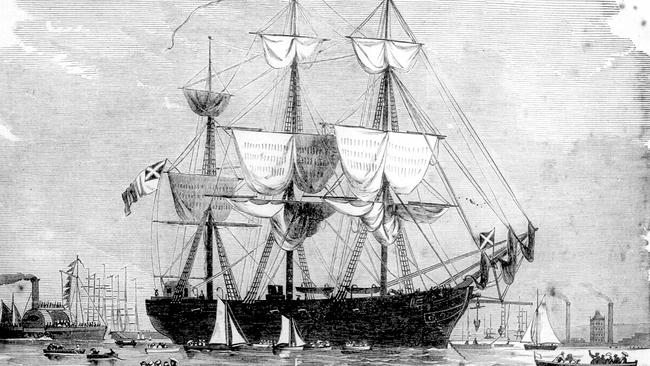

At the time, the Shenandoah was destroying the Yankee whaling fleet in the Bering and Arctic seas. Officially, the Civil War had ended months earlier; president Abraham Lincoln had been assassinated and Confederate president Jefferson Davis had been incarcerated.

Apparently unaware of these historic events, CSS Shenandoah, under the stoic command of Captain James Iredell Waddell, was still at war, flying the rebel battle flag. How the warship came to be in these waters, laying waste to the American whaling fleet, is the subject of Smyth’s enjoyable book.

The American Civil War is often assumed simply to have been a battle between opposing armies fighting on land. While bloody encounters across the American landscape, from Antietam to Gettysburg to Vicksburg and beyond ultimately determined the Union’s triumph, naval strategy played a pivotal role.

As devised by General Winfield Scott in the Anaconda Plan, the south’s ports were blockaded and the rebels denied diplomatic and material contact with the outside world. In reply, the Confederacy challenged the blockade, either by directly confronting the superior United States Navy, or by encouraging blockade runners to deliver vital war materiel by stealth. Finally, the Confederacy sanctioned privateers to raid and destroy US maritime commerce. The three most famous Confederate raiders were Alabama, Florida, and Shenandoah.

Smyth details Shenandoah’s conversion from the British cargo vessel Sea King to a formidable fighting ship. This was the product of the labours and creativity of the Confederate agent in Britain, James Bulloch, whose constant diplomatic struggle with the US ambassador to the Court of St James, Francis Adams (son and grandson of US presidents), is an engaging minor thread in Australian Confederates.

Shenandoah could travel either by sail or by steam. But there was one serious problem for the rebels. The vessel was chronically undermanned. Waddell needed continually to recruit extra men for his crew.

After a refitting in the Azores, Shenandoah began the journey to Melbourne, capturing or burning US ships encountered on the way. Wherever possible, sailors from captured American vessels were enlisted into service.

On January 25, 1865, Shenandoah arrived in Melbourne, to rest and refit. While neither Britain or France recognised the Confederate States of America, Britain had extended belligerent status to the rebels. Shenandoah was entitled to a brief stay in the Australian port, but not to recruit British subjects for war service.

However, there was no doubting the strength and warmth of Melbourne’s welcome. The ship’s assistant surgeon, Fred McNulty, remembered: “Never was conquering flag at peak hailed with half such honours as we were given upon that bright tropical morning. Steamer, tugboat, yacht —— all Melbourne, in fact, with its 180,000 souls, seemed to have outdone itself in welcome to the Confederates. Flags dipped, cannon boomed, and men in long thousands cheered us as we moved slowly up the channel and dropped anchor.”

Indeed, while there were sceptical and critical voices raised, Melbourne’s reception of Shenandoah and its crew was overwhelming. Invitations to every kind of social event were extended to Waddell and crew. They were feted and ostensibly observed all of the colony’s laws and customs. But quietly they had a secret objective, running in parallel to refitting and refurbishing: recruiting Australian manpower.

Smyth canvasses the reasons for Victorian sympathies resting with the Confederates. Perhaps there were enduring memories of the defiant American diggers at Eureka, or it was a just a matter of siding with the underdog. Perhaps Britain’s diplomatic antipathy towards the US coloured the colonial perspective. Smyth also suggests the racism inherent in the practice of “blackbirding” for the Queensland cotton and sugarcane fields may have encouraged a broader acceptance of the “peculiar institution” of the American south.

Smyth writes with an easy hand and Australian Confederates moves along confidently and clearly. Occasionally, the author descends to a colloquial style that is less than convincing, such as when the US consul, William Blanchard, is “fit to be tied”.

After considerable diplomatic manoeuvring, Shenandoah departs Melbourne. Magically, its manpower woes ease. Smyth writes: “As the Shenandoah rolls into international waters, the ship’s complement suddenly increases by 42. From their cramped hiding places in the hollow bowsprit, the water tanks and the lower hold, the Australian recruits emerge and muster on deck.” Thus, the Australian contribution to the doomed Confederate war effort becomes substantial.

This book is a well-crafted account of a largely unknown chapter in Australia’s maritime history and a valuable contribution to our understanding of Australian involvement in America’s bloodiest conflict. It appears undeniable that the American Civil War is the only major war in which some Australians and most Americans were on opposing sides.

Stephen Loosley is chairman of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute in Canberra.

Australian Confederates: How 42 Australians Joined the Rebel Cause and Fired the Last Shot in the American Civil War

By Terry Smyth

Ebury, 371pp, $34.99

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout