‘Teflon Don’: the violent, glamorous gangster who couldn’t be caught

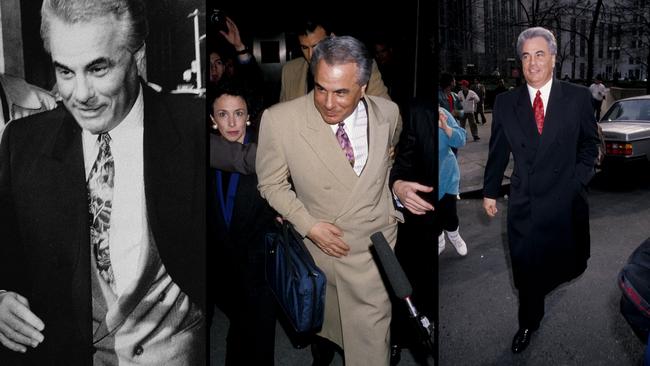

Few gangsters have been admired and envied more than the infamous John Gotti, who with his expensive suits, lavish parties, and illegal dealings, was a media celebrity in 1980s New York.

Just what is it that fascinates us about the American gangsters and the way they remain a kind of social symbol? Why do they still act as a complex image of the American myth of access and social mobility, even as typically they overreach themselves and fall to destruction? Just why are they still treated as celebrities and not criminals worthy of our contempt?

In films, novels and TV shows, we love these monstrous figures and the melodrama surrounding them, often working-class characters motivated by a desire for power and the acquisition of enough wealth to impose their will on the world. Is it maybe our fascination with power itself, and the way gangsters seem to possess an uncanny, almost supernatural organising ability that being outside the law seems almost limitless?

“We grant mobsters dignity because we enjoy contemplating the general principles by which they are supposed to have lived: omertà, standing up to unfair authority, protecting your own,” writes Maria Konnikova, author of The Confidence Game, her forensic examination of the dark art of the scam.

And few have been admired and envied more than the infamous John Gotti, who with his expensive suits, lavish parties, and illegal dealings, was a media celebrity in 1980s New York. Initially dubbed “The Dapper Don”, he soon became known as the “Teflon Don”, the violent, glamorous gangster who couldn’t be caught.

He’s the subject of the fascinating new Netflix true crime series Get Gotti, which follows the way this mobster, who’d grown up on the streets of New York – in and out of prison several times in his early career – arrogantly worked his way up to becoming the most powerful man in New York.

Get Gotti is another entertaining and very stylish series from innovative genre-hopping British production company RAW, who also produced the popular Don’t F**k with Cats for Netflix, the story of one of Canada’s worst murderers, Luka Magnotta and how a global mob of digital vigilantes tracked him down.

And more recently Fear City: New York vs. the Mafia, which investigates the initially tardy, and somewhat inept, but then highly successful attempt by the US government to pursue and convict hitherto largely untouchable mobsters in the early 1980s.

This time the show is directed by Sebastian Smith, mainly known for his exceptional editing skills, having cut numerous high-end documentaries and docu-dramas for major broadcasters on both side of the Atlantic including BBC, C4, Five, Sky, The Discovery Channel, National Geographic, and The History Channel.

His producer is up-and-coming former lawyer Phelan Glen, fast making a name for herself in the burgeoning TV factual world for her ability to gain sensitive access and gaining the trust of key contributors who have broken both new and old stories open.

And she and Smith provide a wonderful cast list of Runyonesque characters with funny nicknames who beat people to death with hammers, their peroxided girlfriends, and the scrounging tabloid reporters who idealised them. And, of course, the cops and feds who eventually brought them down after a long cat-and-mouse chase, smiling tiredly with nostalgic pleasure, their ethical attitudes evoking the chivalric code of the feudal past.

Like Fear City, the new three-part series is part riveting mob story, part police procedural and part courtroom drama. And it’s centred on the way the ghostly presence of New York’s Mafia was given a fleshly solidity and vitality in the presence of gang boss John Gotti. Aided and abetted by a supplicant tabloid press and the presence of a new sensationalist approach to TV news coverage.

The Mob, aka the Gambino family, was supposed to be a secret society – despite the scintillating glimpses of shootings and shakedowns and those photos of bloodied, bullet ridden bodies – but the beautifully coiffed Gotti flaunted it. He acted like a film star, and the public loved his nihilistic outrageousness. As reporter Barbara Nevins Taylor says, he was the perfect character for New York at that time, likening him to a “Marvel superhero before there were Marvel movies”.

He represented a criminal enterprise that dominated the city, “its hand in the corporate glitz of the 1980s and its heart in the sentimental sepia of a bygone era”, as the New York Times wrote at the time. The newspaper described an organisation “with all the accoutrements of a global business cartel, with sophisticated operations to move drugs and swallow enterprises, with Swiss accounts to launder money and elaborate legal, financial and technical adjuncts.”

Andrea Giovino, described as a “Gotti Associate” in the series, says with some delight, “New York in the 80s was a great time to be a criminal, like you could get away with anything, you could get away with murders, drug deals, extortion. We owned New York.” She and her cohorts were making millions in the streets, she says. “Everything was about mink coats, jewellery, everything about it reeked glamour.”

Avuncular Anthony Ruggiano Jr, who acts almost as a narrator diverting us with stories from inside the organisation at the time, puts it like this: “We started out our day with some danishes and coffee and then we went out and pillaged and plundered New York City for the rest of the day.” (A ranking member of the crime syndicate at the time, Ruggiano later flipped sides to save his own skin.)

Gotti’s ascendancy begins on the evening of December 16, 1985, when, with grand impudence, he orchestrates the murder of 70-year-old-mafioso Paul Castellano – the apparent successor of recently deceased Gambino family boss Aniello Dellacroce, the Gambinos the most powerful of the criminal groups running the Mafia.

Sparks’ Steak House, a popular hangout for major criminals, was the scene of the crime; Castellano gunned down along with his number two in command, Thomas Bilotti, in front of the restaurant. “That’s like shooting the President, who would have the balls to kill the boss of bosses?” says Giovino in the series.

Gotti takes charge but quickly becomes the most surveilled man in the city. And the series juxtaposes Gotti’s reign as the Boss with the efforts of both the FBI and the New York City-based Organized Crime Task Force (OCTF) to investigate him. It’s beautifully handled, too, by Smith who gives us the inside story of just how a criminal investigation is put together, not always harmoniously, the two agencies fiercely competitive. Every legal jurisdiction wants Gotti.

The interviews with the various detectives and agents, still excited with having been part of history, are inventively filmed, each of them placed in diners or coffee shops that featured in the original investigations. Some happen in period cars, the old-timers driving, as if the cops are still on surveillance or tailing the bad guys.

They chronicle their efforts to videotape the crims and the painstaking process of somehow producing audio recordings, largely from their favourite haunt, the Bergin Fish and Hunt Club in Ozone Park, a pair of nondescript brick storefronts secretly connected on the inside, where Gotti held court.

It’s a treat to watch for the show’s exciting visual aesthetic, loaded with the prestige sheen that characterises the Netflix true crime boom, the interviews cleverly tailored to maintain a sense of theme and character.

Smith uses a heightened audiovisual style with a hyperkinetic aesthetic, flashing neon signs, almost psychedelic chyrons carrying pieces of information, chronology and grabs of newspaper stories, split screen in which contemporary imagery is contrasted with nostalgic shots of the same things, dynamic aerial sequences of New York itself, and loud blasts of period pop songs.

At times it’s all like a symphony of excess mirroring the feel of the eighties, a witty sensory surfeit that never lapses into incoherence or discontinuity, tightly controlled by editor Hugh Williams.

Get Gotti, streaming on Netflix.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout