Tasmanian journalist Charles Wooley considers Tasmania’s violent past

A new account of Tasmania’s violent and bloody history forces all Australians to confront our cultural amnesia.

I grew up in Tasmania having never heard of a man called Tongerlongeter (let alone knowing how to pronounce his name) and I was not alone. I can confidently assure mainland readers that before the publication of Tongerlongeter: First Nations Leader and Tasmanian War Hero, the number of Tasmanians who had even heard the name might have held a meeting in the smallest alcove of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery.

The authors, Henry Reynolds and Nicholas Clements, have worked some powerful historical magic to conjure out of a dark and foggy Tasmanian past, the image of a tall, handsome, noble warrior named Tongerlongeter, whom their book subtitles as a “First Nations Leader and Tasmanian War Hero”.

From the moment I started to read this disturbing book I almost wished I had never picked it up. In Tasmania we have a preferred narrative: a comfortable historical amnesia concerning our violent and bloody history on this beautiful island. I grew up in a time when respectable Tasmanian families found it convenient to forget their convict ancestry. That heritage was often referred to as ‘the stain’.

Only relatively recently has it become fashionable to have a transported scallywag in the family. But what has remained is an even darker secret: the role played by the white invaders, the convicts, soldiers, government and free settlers in the systematic killing of those other Tasmanians, the Palawa, who had been here for 40,000 years.

We don’t even know how many there were; estimates vary between 3000 to 15,000 so there is still plenty of room for further historical scholarship. But such inquiry will always reveal a dreadful ignominy, so much worse than the convict stain. And there are no cleansers and sanitisers powerful enough to remove the foul blotch of genocide. Relentlessly Reynolds and Clements sift the historical evidence to lay their charges. They quote John West, an early authority, describing a common enough campfire ambush to punish Tasmanian natives who might have taken a sheep.

“No one will question the atrocities by commandos, first formed by stockkeepers and some settlers, under the influence of anger and then continued from habit. The smoke of a fire was the signal for the black hunt. The sportsmen having taken up their positions, perhaps on a precipitous hill, would first discharge their guns, then rush towards the fires and sweep away the whole party. The wounded were brained; the infant cast into the flames; the musket was driven into quivering flesh; and the social fire around which the natives gathered to slumber, became, before morning, their funeral pyre.”

Such attacks were so commonplace that an east coast settler’s account from 1830 is unsettlingly casual.

“We all six noiselessly approached to within a few yards of the wretches, when all of a sudden the dogs gave the alarm… the natives were on their feet like electricity, but they looked stupefied and made no attempt to run. It would have been all the same if they had, for we had them nearly all under the cover of our guns, which we discharged at once, and dropped some eight or ten like crows. Then there was a jolly scramble to make off, but we dropped a few more as they bolted away into the scrub.

“Our night’s sport made a dozen less natives, whom we left there to rot, and we sent away several wounded.”

From the first contact with Tasmanians in 1804 the British colony in Van Diemen’s Land quickly descended into what would now be considered ‘racist’ barbarity. Reynolds and Clements chronicle the infamy with detailed first-hand accounts of murders and decapitations, abductions, rape and torture of the Indigenous population.

Inevitably there would be payback. Nemesis when it came was much in the form of a Hollywood R-rated revenge movie. Indeed Tongerlongeter (if we can all agree on the pronunciation) would make a great Australian “get square” film.

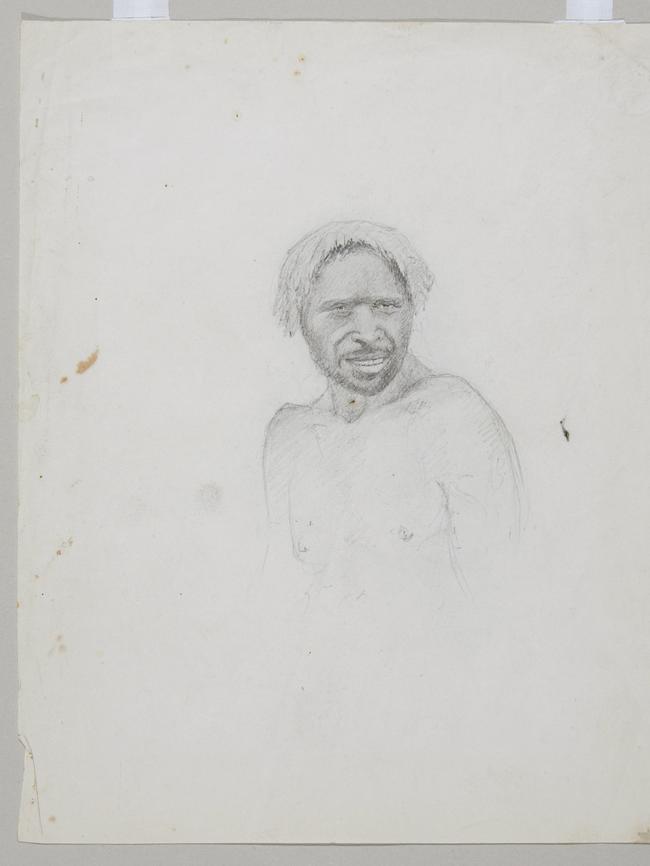

The book even comes with illustrations of its hero in the form of an 1832 pencil sketch and watercolour by the convict artist Thomas Bock. Broad browed, firm jawed and athletic looking, the image is of a freedom fighter from central casting.

In a sense the illustration has to say it all. Tongerlongeter of course wrote no manifesto, no Jerilderie Letter, nor did he preach a Sermon on the Mount. Remembering what has been deliberately forgotten makes for a most cryptic history.

Professor Reynolds and his one-time PhD student Nicholas Clements have gleaned far and wide for scraps of information, from newspapers of the time, settler’s journals, letters and government records to pluck their hero out of total obscurity. Appropriately at the beginning of this 268-page account, they declare, “We have done our best to provide an accurate picture of Tongerlongeter’s life, but in some respects, he remains as elusive to us as he did to the colonists.”

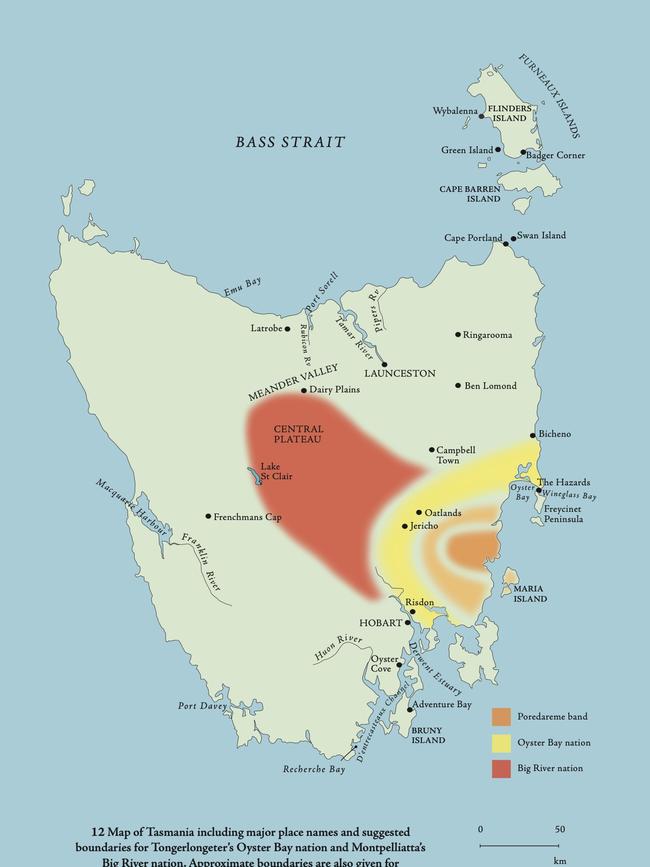

As the authors tell it, Tongerlongeter raised a guerrilla force from the island’s two major tribes, the Oyster Cove (East Coast) and the Big River (Central Tasmania), and by the late 1820s he was creating havoc and fear among the colonists.

Combining stealth with an implicit knowledge of the bush, the native Tasmanians murdered and plundered the settlers and attacked the military. The authors suggest the intention was probably “to exact revenge proportionate to the numbers of their countrymen who had been killed”. Tongerlongeter’s Tasmanian warriors soon figured out the white men had only one shot in their muskets and needed time to reload. After the first volley the guerillas would rush to engage in close combat and the authors remind us, “It is likely the advantage would have been held by the warriors, who were bigger, stronger and fitter than the British defenders.”

Henry Reynolds is one of Australia’s foremost authorities on what are now known as ‘the Frontier Wars’. These occurred in every state but nowhere so fiercely as in Tasmania where, until recently, history told a different story.

I grew up learning that it was a contest between the most primitive people on earth, who couldn’t even boil water, up against invaders who had invented the steam engine.

I was always taught that Aboriginal people were victims rather than serious combatants. I was also told the first Tasmanians had entirely ‘died out’.

At school we somehow had to reconcile our history lessons with an everyday contradiction. Among our mates were a cohort of dark-skinned and curly haired kids who were exceptionally good at sport.

Eventually I came to realise the Tasmania of the Sixties in which I grew up wasn’t idyllic for everyone. For the descendants of the first Tasmanians my home state was indeed the “Deep South”.

One day after sport, the proprietor of a Launceston milk bar, near my high school, said to us white kids, “Youse are OK, but not your mates. I won’t have any bloody abos in my shop.”

Back in the Sixties Launceston was Alabama, without the Civil Rights Movement and the music. It has always remained a personal regret that I didn’t stand up for my darker-skinned mates in that milk bar. I must have known it was wrong because I still remember it so vividly.

But I was 13 and I knew nothing. For me and hopefully for all Tasmanians, Reynolds and Clements provide some redemption by resetting the blackest history with a disturbing but uplifting book.

As the authors note in their introduction: “Admiration for people like Tongerlongeter transcends race, culture and creed – he is someone we can all look up to.”

To my surprise the book has become a Tasmanian bestseller and I hope those kids who were so long ago shamefully chucked out of that milk bar, now get to read it.

Although this book is a work of imagination as well as historical plodding, I am sorry to say there is no happy ending. But even if until now you’d never heard of Tongerlongeter, I am sure you have already guessed it.

This is a story that ends badly.

Charles Wooley is a writer who lives on a Tasmanian beach.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout