Tabitha Carvan’s book about Benedict Cumberbatch is captivating for all the wrong reasons

Australian science writer Tabitha Carvan’s fixation on the British actor known for his interpretation of Sherlock Holmes is the strangest memoir I have ever read.

When I say that Australian science writer Tabitha Carvan is obsessed, I do not mean it in the colloquial sense, where one’s thoughts return, with amusing regularity, to teriyaki salmon, Sudoku, or to Megan Fox and Machine Gun Kelly, but where one is in the grip of a compulsion.

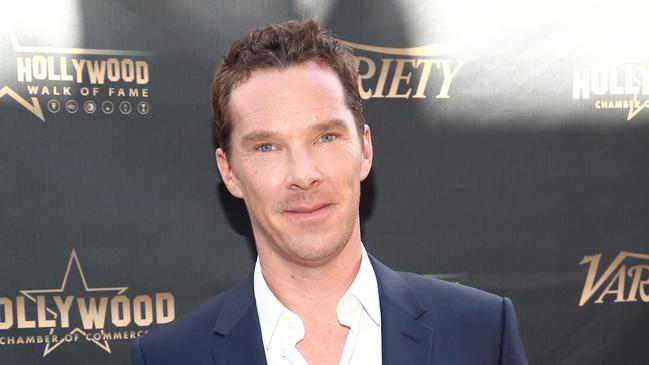

The focal point of Carvan’s fixation is Benedict Cumberbatch, the graceful, privately educated British actor known for his interpretation of Sherlock Holmes, whom her mother unforgettably describes as looking “like the underside of a stingray”.

This Is Not a Book About Benedict Cumberbatch, the by-product of this obsession, is the strangest memoir I have ever read.

Fogging up the windscreen, Carvan begins: “I am writing this between thoughts of Benedict Cumberbatch, and I am writing this under photos of Benedict Cumberbatch, including that Vanity Fair cover where he has one arm behind his head and the other tugging at the waistband of his trousers. It is the most horizontal that a man could look in a vertical portrait.”

It soon becomes apparent that Cumberbatch symbolises everything Carvan, in her floral frocks and footless tights, feels she will never have – artistic glamour, high society verve, sexual sophistication.

But then it starts to get weird. Carvan, you realise, isn’t just being cute. The tenor becomes shrill.

This is not literary froth but a document of fixation over which Carvan seems to have nominal control. She has a not quite breaking-into-Cumberbatch’s-house-to-sniff-his-glove stalker-grade fixation, but somewhere in the ballpark.

“I’m writing a book about how I fell in love with Benedict Cumberbatch HAHAHAHAHA,” she tells a group of writers. “I wanted to make sure they knew I was in on the joke. It seemed natural to me – no, it’s more than that – it seemed necessary to me to recognise the not-rightness of my obsession; to get in first and acknowledge that it is … almost negative HAHAHAHAHA.”

It’s as if the book were an attempt to manage or justify Carvan’s Cumbermania, the dimensions of which had, perhaps, come to feel unnerving.

Carvan’s husband shrugs it off. “Have fun with Benedict!” he shouts on his way out. He bakes her Cumberbatch cakes for her birthday. The ratio of his mentions to those of Cumberbatch is, however, something like 1:10. And then there are their two children, about whom Carvan writes, “I’m sorry this story about such a momentous occasion is so boring, but that’s motherhood.”

In an earlier essay, Carvan, a “hostage” to motherhood, wrote that it was Cumberbatch, rather than either of her babies, who “reached inside of me and restarted my heart”.

Without any consciousness of the ideological foundation of her priorities, Carvan puts her infant daughter in her bicycle trailer and “drags” her to daycare, where the baby is deposited, leaving Carvan “unhindered. Nothing would weigh me down! Nothing would hold me back!” When there is an outbreak of gastroenteritis at the daycare centre, Carvan’s concern is not that her child may be ill but whether she will have to sacrifice her work to play “carer”.

Carer? When did motherhood start being understood through the legal prism?

To the emotionally adolescent Carvan, motherhood is something like being “stuck in an interminable holding pattern, circling the airport and dumping fuel. And the in-flight entertainment is broken. It just goes on and on, tediously. I was praying for something to hit me, just to break up the monotony.”

Nervously, she backtracks (“I love my kids!”, “They are the absolute greatest kids”, “I wouldn’t swap them for anything”, etc), but the contrast to the forensic specificity with which Carvan recalls Cumberbatch (“I note the impressive accuracy in the placement of [his] neck freckles”), the generic nature of these few endearments tells its own story.

Carvan, far from being the jolly suburban superfan of her publicity shots, is, in fact, a woman who desperately needs to be distracted from elisions she does not know how – or want – to face. Captivating for all the wrong reasons, This Is Not a Book About Benedict Cumberbatch is her cri de Coeur. It reads like a tightly-crafted monograph by a troubled mother whose increasingly frantic attempts to suppress her despair demanded attentional rerouting.

Antonella Gambotto-Burke’s new book, Apple: Sex, Drugs, Motherhood and the Recovery of the Feminine, can now be pre-ordered.

This Is Not a Book About Benedict Cumberbatch

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout