Sven Lindqvist’s Terra Nullius: a problematic view of Australia

Sven Lindqvist’s Terra Nullius has emerged as a defining account of Australia’s place in the wider world.

A decade ago, the veteran Swedish writer and connoisseur of colonial oppressions Sven Lindqvist released Terra Nullius: A Journey Through No One’s Land, his bleak account of a season spent travelling the highways of remote Australia and turning over the half-forgotten history of the Aboriginal frontier in his thoughts. The book remains in print, and influential among foreign readers.

It has recently been republished in handsome new editions by Granta in Britain and the New Press in the US and, much like Bruce Chatwin’s The Songlines or Marlo Morgan’s contentious Mutant Message Down Under, is on the way to becoming a classic of antipodean journey literature, a canonical introduction, at least for international audiences, to the Australian past: one of the handful of touristic memoirs that define this nation’s image in the wider world.

But the brief reviews of Terra Nullius by Australian critics when it was published here in translation in mid-2007 were, for the most part, sharply, scornfully critical. The expatriate writer Peter Conrad diagnosed a bad case of political correctness in Lindqvist, and even hinted at a moral cowardice in the book’s perspective. The historian Inga Clendinnen, widely seen as an arbiter of fine-honed judgments, felt Lindqvist had come to Australia with his mind closed and eyes wide shut.

There is a pattern here, and a problem. Mainstream Australia’s idea of itself and the local literary intelligentsia’s widely shared conception of a modern, progressive Australian nation-state are at variance with the view of the country that prevails abroad. Australian voices and Australian accounts of the colonial past usually do not carry weight with general audiences overseas — with the sole exception of that perennial favourite of rip-roaring, journalising history, that catalogue of foundational atrocities, Robert Hughes’s The Fatal Shore. The prominence of Australian writing in the world has declined over the past four decades despite the spreading popularity of exotic literatures in Western markets, and despite the best efforts of Australia’s state-funded cultural promotion agencies.

Books such as The Songlines and Terra Nullius have, of course, something in common, something that lies at the core of their appeal for foreign readers: they are principally about Aborigines and their cultures, and the harsh story of the colonial frontier and its modern consequences. Despite the substantial, nuanced and deliberative Australian literature and history dealing with these themes, local writers are inevitably viewed by foreign readers as suspect authorities. Outsiders, though, can be seen as independent, veridical, well placed to see the buried patterns in the history of the continent.

Hence the particular importance of a book such as Terra Nullius, and the significance of its longevity and its emergence as a standard work. Hence the need, now the initial flash of its first release is done, to sift its presentation of events and its arguments anew: the claims Lindqvist makes, the analogies he draws, the abrupt shafts of light he sends down into a past Australian historians see in a more fine-grained frame.

Over the course of his career Lindqvist has developed a distinctive style. His extensive Saharan travels paved the way for his best-known book, Exterminate All the Brutes, an account of European colonial cruelties in Africa. He runs three components together in staccato fashion: an eyewitness account, usually sketchy, of the places he passes through; a scatter of reflections drawn from his childhood; and excerpts from the scientific writings on race and anthropology that shaped the colonial enterprise. This is the method employed in Terra Nullius: the parallel drawn between the African and the Australian record is explicit — indeed, the new US edition, published by New Press, includes his Australian travelogue as a kind of sequel in the same volume as his chief Saharan narrative, under the joint title of The Dead Do Not Die.

Lindqvist begins his tale as he means to continue: with a combative and artfully managed presentation of the evidence. He checks in at the South Australian Museum, the greatest repository of anthropological expertise on the continent, and elicits a blank from the information desk when he asks about Moorundie, the site of an early massacre. From here, the road leads up towards the Stuart Highway and Port Augusta, where Lindqvist meets his first Aborigine, a woman changing money in the gaming hall of the Pastoral Hotel: “We avoid eye contact.”

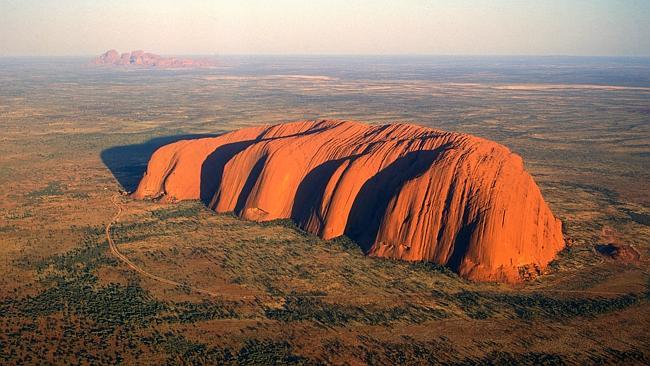

The way stations from then on are the standard ones: Woomera, where he seeks to draw analogies between contemporary treatment of asylum-seekers and past treatment of Aborigines, then Ayers Rock and Alice Springs, which makes a poor impression. “Aborigines are to be found working in private and government offices, as shop assistants, janitors, and parking attendants, and as troublesome drunken layabouts in the parks. I see them as clients at court, as hospital patients, as artists in art galleries, and occasionally as restaurant guests, usually in the company of white people. I practically never encounter an Aborigine in any situation offering an opportunity or reason for ‘meeting’, ‘talking’, ‘going for a coffee’ or even acknowledging one another’s existence.”

And how hard it is to get permission to go to remote communities! “Well,” muses Lindqvist, “why should a long-despised people, now it is no longer faced with certain annihilation, go about longing to socialise with its former annihilators and despisers? Why should a long-exploited people be prepared to offer itself as an exotic, unpaid bait in the tourist traps?”

There is much in these surface observations that is perceptive and accurate, and much that is subtly out of true, as is the case with a number of Lindqvist’s interpretations and conclusions, and as would be the case if a traveller from a different culture made a trip through Sweden or any other Western country and tried to provide an anatomy of its most complex social issues after a brief look round.

Of course the fresh, unknowing eye sees things the local can never see: the naive perspective has its value. But when it comes to history and the thought-world of today’s Australia, first impressions are a less certain guide.

Lindqvist’s views inevitably reflect the limitations of his reading matter, which he draws on constantly and lists at the back of his book — and the book reads very much like an accretion of all these guide points. The characters who loom in its narrative are the usual anthropological suspects: Daisy Bates, Spencer and Gillen, Theo Strehlow, Radcliffe-Brown. The villains are also the familiar ones — the West Australian chief protector of Aborigines and architect of child removals, AO Neville, the Kimberley grave-robber Eric Mjoberg, even William Willshire, the vainglorious Central Australian commander of native police. These figures are all examined against the backdrop of the particular landscape where their words and the memories of their actions still resonate.

Indeed the route Lindqvist follows is in essence the one laid out in John Mulvaney’s essential guide to frontier meetings between cultures, Encounters in Place. Hence visits to the park where Kahlin Compound once stood in Darwin, to Roebourne jail and to the site of the Pinjarra massacre are dutifully ticked off — the must-see destinations on the disaster trail. Lindqvist also passes close to a number of remoter points of conflict, and dwells on their histories: Wave Hill, on the edge of the Victoria River District, the scene of the 1966 walk-off by Aboriginal stockmen, and Bernier and Dorre Islands, isolation hospitals where Aborigines with infectious diseases were kept in harsh conditions a century ago.

Like many outback travellers, he is overwhelmed by the country. Here he is, driving the featureless Great Northern Highway on the 600km stretch between Broome and Port Hedland, and tempted to equate the seeming desolation of the plains around him with his view of the continent as a realm stripped of its heritage, a no man’s land: “There are no roads leading out into the desert, no roads leading down to the sea; nothing happens along the road except the grubby and dilapidated little Sandfire Roadhouse, totally free of any redeeming features. There’s a turn-off down to an equally charmless campsite by the beach, from which you are grateful to return to the main highway.”

A defender of the country might argue that Sandfire is full of history, and Eighty Mile Beach full of fascinating, slowly revealed beauties, while the desert inland off the highway is Australia’s most majestic dunefield parkland, alive with lovely sights and mysterious sounds — but Lindqvist is hurrying through, absorbing only what the eye in its first scan sees.

Here he is overflying the southern desert in a light plane, looking down on salt lake country, bound from Ceduna to Alice Springs: “I see black fern patterns in light sand. I see light ribs on a dark background — an opened chest cavity … The ground is striped and fingered, full of riverbeds without rivers. Crisscrossed by innumerable runnels that aren’t running anywhere, traces of water events that used to happen once but aren’t happening any more. A history wholly characterised by its landscape. A landscape wholly characterised by its history or, to be more precise, its water history. You feel you could read the ground as Sherlock Holmes reads the scene of a crime. The bulldozers have left behind a few straight red tracks in the ash-gray sand and white salt. Wind and water have left behind innumerable meandering tracks, branching and rejoining each other, in nature’s marshaling yard.”

Bleak analogies, but active ones, the products of a questing, inquiring eye and mind — which makes Lindqvist’s reluctance to report any impressions from his field trips to remote Aboriginal communities all the more puzzling. Even the academic Robert Manne, in his broadly favourable overview of Terra Nullius, remarked in some perplexity that Lindqvist “appears to have taken almost no interest in contemporary Aboriginal societies” — though, by the book’s own testimony, he made road trips to such tangibly indigenous places as Laverton in WA and the Northern Territory communities of Hermannsburg, Papunya and Yuendumu. It may be that these brief visits yielded insufficient material for reflection, or that the locals were indeed unwilling to offer themselves to him as “exotic, unpaid bait”, and it may also be that Lindqvist prefers the dark history of the colonial era to the messy, complicated attempts at ground-level social development under way in the bush, where Aboriginal people of traditional accent can be found subsisting within the Australian nation-state.

Instead he presents the bush settlements of the recent past as places of horror, close cousins to the carceral institutions he knows from other continents: “Papunya was the jewel in the crown of the little gulag of native internment camps set up to implement the policy of assimilation.” He believes desert nomads were rounded up and herded into controlled communities “where they were kept while their culture was soaked off them, like removing paint from old wooden furniture with lye”.

Rather than providing direct testimony to support this fantastical interpretation of the flow of events, he falls back on his staple source material, the literature, selectively sampled, and above all the best known and most highly coloured record of the dawn of the Aboriginal desert art movement in Papunya. Lindqvist makes a special pilgrimage to Taree in NSW to visit the ailing impresario of the first bush acrylic paintings, Geoff Bardon, whom he finds tongue-tied and two weeks from death.

But the arc of the story is already set: Aboriginal art is the sole thing of weight and merit to have emerged from Australia. An “educated minority” in the modern cities of the coast is at last alive to this culture: “They are recognising that this supposedly doomed ethnic group is actually displaying exceptional powers of survival. Contempt gives way to admiration as they see the consistency with which the Aborigines have held fast to the foundations of their traditional culture and the flexibility with which they have been able to adapt it to modern technology and modern society.”

As is clear from his first pages, Lindqvist is clearly pursuing an idea in his account of Australia, rather than developing a portrait on the basis of things seen, felt and learned on the ground. Here it is, put plain in all its simplistic certainty: “Similar crimes were being committed around the world: in Canada and the United States, in South America and South Africa, in North Africa and Siberia, in central Asia and central Australia — in fact wherever European settlers were in the process of taking land from its original owners. The extermination of the Aborigines produced the no mans land, which according to the doctrine of terra nullius gave the white settlers rights to the land.”

The facts of the matter are not the point here — the point is the sweep of the thesis, and its appeal to Western audiences, and its capacity to entrench a particular view of Australia. Lindqvist goes through to his climax: the need for the new Australia to “face up to the crimes committed by the old one” and come to terms with its past. This redemption is to be accomplished by redress, by acknowledgment, by acceptance. “When the misdeeds of the past are brought to light, when the perpetrators and their heirs confess and ask forgiveness, when we do penance and mend our ways and pay the price — then the crime committed has a new setting and a new significance.” So Lindqvist, in his final flourish.

And here, right here, is the double bind. Books such as Terra Nullius, with their prosecuting zeal and their stark presentation, are viewed as preposterously unfair by Australian critics and readers, and dismissed — and that dismissal reads like denial to foreign eyes. Unfair, slanted, biased — but behind this wilderness of bias is a palpable mountain range. Lindqvist is writing about a great transition in history, the first, colonial globalisation and its attendant conflict. He deals with the one big, glamorously dreadful thing in the Australian past: invasion, extirpation, conquest — a record that, to some Australian eyes, seems gainsaid by the particularities of national experience, but that conforms, when viewed from outside, to a dark, plain charge sheet, backed by ample evidence.

The Lindqvist paradigm still casts a shadow. Australian writers, as sculptors and refiners of Australia’s image and aura in the wider world, work beneath this penumbra. Even today, national history is almost always tinged by racial history, landscape is purloined landscape, race is lurking everywhere. But the deeper drama is not where Lindqvist and outside judges of his kind would locate it, in a choice between defiance or sackcloth and ashes. It is in the long persistence of racial categories and concepts, which rule out the emergence of a Mestizo Australian culture on the lines of other postcolonial countries of the southern hemisphere — places where national narratives have begun to erode classification in terms of race.

How to write into this headwind, and face the past while escaping it, and escaping the stereotypes about Australia that circulate worldwide? Given the modern cultural establishment’s strong penchant for critique of the West and keen appetite for moralising judgment, this is a dilemma, not to say a curse, that will not be easily or soon lifted.

Nicolas Rothwell is a senior writer on The Australian.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout