Suburbia, by Jeremy Chambers: dark vision of Oz life, not a fallen one

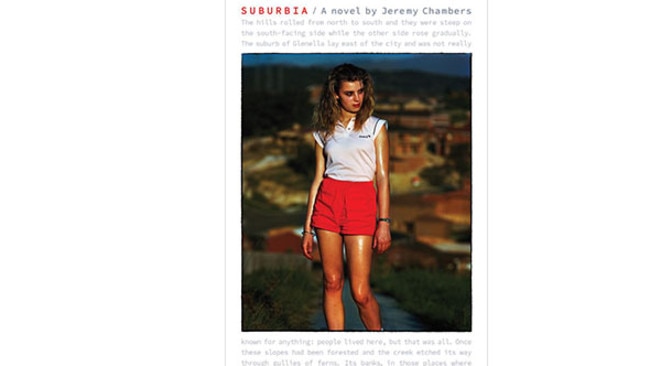

Suburbia paints the neon-hued, big-haired, acid-washed landscape of the 80s with Heidleberg School exquisiteness.

“It is an illusion that youth is happy, an illusion of those who have lost it,” Somerset Maugham wrote more than a century ago. “The young know they are wretched for they are full of the truthless ideals which have been instilled into them, and each time they come in contact with the real, they are bruised and wounded.”

The mode may be pensively Edwardian but the insight is durable. Jeremy Chambers’s second novel takes as its subject the worldly education of a boy coming of age in Melbourne’s outer-eastern suburbs during the 1980s.

Roland Arthurson — Roly — is the quiet, dreamy, watchful son of middle-class parents. He runs unquestioningly along the tracks laid down for him: studies hard, looks after his sister and is faultless in his dealings with adult neighbours who, over time, become family friends.

First among these are Reg and Carrie Noble. Reg owns the local car dealership and is a Vietnam veteran. He is loud, aggressively masculine and hard-drinking, though not lacking rough charm. His wife is also a slightly extreme version of an older Aussie type, favouring stiletto heels, pedal pushers and a generous, deeply tanned decolletage. The couple are vulgar and virile, and fascinating to the more dowdy, earnest, educated Arthursons (class and its subtle demarcations are closely marked but not lingered on throughout).

Most significant for Roly is the presence of Reg and Colleen’s daughter, Cassie, at the family’s rolling Sunday lunches. She is attractive, impetuous, astute, precocious: an utterly beguiling figure to a heterosexual boy about to enter his teens. It is by bearing witness to Cassie’s personal dramas in years to come that Roly realises the chasm that exists between the ideology of adulthood promulgated by these authority figures and the battering facts of lived experience.

As with his feted first novel in 2010, The Vintage and the Gleaning, Chambers is not single-mindedly concerned with the simple passage of narrative, though he manages to turn this slight domestic material into something engrossing. Rather, he is concerned with the micro-textures of time and place. His is an ecological imagination: it places humans within a landscape but does not automatically foreground them. In this approach, each aspect of the world demands an equal share of our attention. So it is that Suburbia describes UDL premix booze cans with the same sensuous relish as pittosporums in bloom. Packs of Alpine menthol cigarettes are lingered upon as naturally as cloud formations.

This is a democratic vision but a curious one. The author’s achievement is to paint the neon-hued, big-haired, acid-washed landscape of the 80s in Australia with Heidelberg School exquisiteness, and in doing so he brings an oddly formal, grave, elegiac air to a moment and a world that seems shallow and silly in retrospect. The registers don’t always mesh perfectly, though when they do the effect can be miraculous, a transfiguration of the commonplace:

The children walked to the pool through the sunlit empty streets, the miles and miles of concrete and bitumen, the rows of identical brown-brick houses that lined the rising hills, their orange-tinted windows blinding in the sun. The grass on the nature strip was lush from sprinkler hoses that ran all day long, thin sparkling arcs dampening the footpath and trickling down the rusty gutters to the stormwater drains. The roads melted, seethed; it turned to black liquid. It shimmered in the distance and made mirages at the rounded peaks and hollows. The children’s thongs slapped the footpath, echoing like rifle shots.

The fluoro orange bikini Cassie wears to the pool that endless afternoon does not escape Roly’s attention, nor the attention of others. Darren, lithe and 19, lives nearby the Arthursons and Nobles but at a lower social strata. His main occupations are tending, lovingly, to his motorbike and drinking by a fire in his yard. Through Darren, Roly will come into contact with a motley group of older boys and semi-criminal men utterly unlike the blond cricketers and perfect prefects with whom he shares a private school. For all their roughness, they offer him friendship and a glimpse of wider adult horizons.

When Darren and Cassie, now 14, get together, Roly is cast into a miserable role of confidant and voyeur to their affair. It is the fallout from this relationship that conclusively detonates the hypocrisy of his suburban elders.

Although we are seated firmly on Roly’s shoulder throughout the novel, we do see Chambers attempting to do some justice to the adults’ point of view. They are flawed, faltering figures whose unwillingness to attend to the experience of their young with the requisite empathy or urgency is damning, and ultimately destructive.

Yet they, too, suffer, as though adulthood came as a relief from an earlier, troubled, primal time, one so raw and scarifying that it, youth, must be forgotten as soon as it is escaped. Remember that it is Reg, the darkest figure in the novel — a man of disturbing, private and seemingly bottomless appetite — who went off to war. The houses in which the families live, the tidy suburbia they inhabit, seem designed to keep some potential anarchy or recurrent nightmare at bay.

These pages reflect a dark vision of Australian life but not a fallen one. They contain a critique of masculine violence while also constituting a modest hymn to male friendship. They acknowledge the drear curb and guttered landscape of suburbia, while finding beauty even in its mundanity. From Chambers’s sentences a picture emerges of the nation as an imperfect Eden: the sky’s endlessly replenishing light falling on the heroes and villains of the narrative alike with pure indifference. Indeed, beneath the hamburger wrappers and cigarette butts that litter the parks, unadulterated nature continues its slow work.

It’s an effect that recalls novels such as James Agee’s A Death in the Family, in which the blind processes of the physical world ennoble human ordinariness; in which evocation is so free-floating, lyrical attentions are dealt out in a manner so generously indiscriminate to all creation, that the result is a kind of agonised, universal tenderness. Bruised and wounded, absolutely, but all the more real for that.

Geordie Williamson is a writer, critic and publisher.

Suburbia

By Jeremy Chambers

Text, 272pp, $29.99