Storyteller Ken Burns is in top form with The American Buffalo

Documentarian Ken Burns captures the casual demise of the buffalo – and the people who revered them – by America’s white settlers.

“I am a filmmaker, but first and foremost, I’m a storyteller, and I happen to work in American history the way a painter might work in oil as opposed to watercolour, or concentrate on still life as opposed to landscape,” documentarian Ken Burns says.

Stylistically recognisable – he practically invented the pan and zoom effect imparting action to still photographs – and cinematically audacious, his memorable documentaries include The Civil War, Baseball, Jazz, The War, The National Parks, The Dust Bowl, Prohibition, Country Music and Hemingway.

His last series was The US and the Holocaust, prickling with outrage, which examined just how much evidence was accessible to Americans during that terrible time, and asked why rescuing Jews was no priority, except for those few individuals who took the risk to help.

Now he returns with The American Buffalo. But don’t be put off by the title. This is no simple elegiac nature documentary. Instead, it’s the story of the way America’s national mammal, the huge, shaggy bison, sustained the lives of Indigenous people, whose cultures were intertwined with the animal.

Burns illustrates in his inimitable narrative-driven way how this noble creature he calls “an improbable, shaggy beast”, running wild for 10,000 years, was commercially exploited and heartlessly defiled.

It’s the story of how, in a momentously short period, the buffalo – the terms are used interchangeably – was almost destroyed by newcomers to the continent bringing with them a different view of the natural world.

Then driven to the brink of extinction, they were brought back by a movement that in time became a conservation success story.

The two-part series is the biography of an animal, which, as Burns dramatises so poetically and evocatively, found itself at the centre of many of an emerging America’s “most thrilling, mythical, and sometimes heartbreaking tales”. And as is always the case with Burns, his four-hour film is also a window into a broader American history.

He presents this resonant story as a morality tale about the ease with which we can destroy the beauty of the natural world. Burns likes to quote Mark Twain’s line that “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes”. And for him the series carries a warning about climate change and “the possibility that many, many large charismatic mammals will go extinct”.

As his series documents America’s Great Plains once possessed one of the grandest wildlife spectacles of the world, equalled only by such places as the Serengeti. Less than 200 years ago pronghorn antelope, packs of gray wolves, vast herds of bison, coyotes, wild horses, and grizzly bears roamed alongside the bison. They existed in such profusion that in 1843 naturalist John James Audubon famously wrote to his wife, “It is impossible to describe or even conceive the vast multitudes of these animals that exist even now, and feed upon these ocean-like prairies.”

The series is directed, and executive produced by Burns, written by Dayton Duncan, and produced by Julie Dunfey and Burns, and Hollywood actors, again part of the Burns’ style, provide the voices of the historical figures giving voice to the off-screen texts – diaries, letters, and official records.

Among them are Jeff Daniels and Derek Jacobi, Hope Davis, and Emmy-winner Paul Giamatti voicing Teddy Roosevelt.

The stories of Native people anchor the series, and Julianna Brannum, a member of the Quahada band of the Comanche Nation of Oklahoma is consulting producer.

And like so many of Burns’ films, its narrative is recounted in that mesmerising way by Peter Coyote, who Burns calls “God’s stenographer”, coolly authoritative, finding sonorous counterpoints in the text, carrying us through those complicated sentences without getting lost in the many subordinate clauses.

Early in the first episode, Blood Memory, Duncan describes the series this way: “It’s not just the story of this magnificent animal – it takes us into all the different corners of our history and how we interact with one another as human beings. It is a heartbreaking story of a collision of two different views of how human beings should interact with the natural world.”

The first episode begins with a splendid evocation of the lost splendour of a luminous country rippling with vast tracts of grasslands and the huge inhabitants of the plains. And Coyote explains how, for more than 10,000 years, the buffalo evolved alongside the Indigenous people who relied on them for food and shelter and “in exchange for killing them, they revered them.”

We’re given the facts about the buffalo, the way it can clear a six-foot fence, or hit running speeds of 35 miles per hour, how they’re, “a souped-up hotrod of an animal hiding in a minivan shell.”

But then the Cheyenne prophet Sweet Medicine warns his people. “There is a time coming,” he tells them. “Many things will change. Strangers will appear among you. Their skins are light-coloured, and their ways are powerful. These people do not follow the way of our great-grandfather. They follow another way.” He tells them these strangers will keep coming, riding round-hoofed animals and will keep pushing forward.

And they come on their horses and then their trains, settlers, hunters, and traders, inspired by the notion of Manifest Destiny, an ideology including the belief that white Americans were divinely ordained to settle the entire continent of North America. And Burns shows how piles of sun-bleached bison skulls were left in their wake to give direction to those that followed.

The Indigenous inhabitants of the plains become mere impediments to the forward march of racial and industrial progress. The slaughter reached astonishing heights, the number of bison collapsed from between 30 and 50 million to just a few hundred, and the lives of countless Native Americans who depended on the animal for existence were destroyed.

“There is a phrase that as settlement moved west, they were redeeming the land from wilderness by the hand of man – by ploughing it, cutting the trees down, by killing the wild animals and replacing them with domestic cattle or hogs,” says Duncan.

As always with Burns his new film is crammed with resonant stories, photographs, and paintings. And great characters. There’s the first European to see bison, Spanish explorer Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, who stumbles across them in the early 1530s, in what is today Central Texas. He described the creatures as “hunchbacked cows”, drifting from the Rockies to the Appalachians.

There’s the nobleman Sir George Gore, who in a single hunting trip to North America from 1854 to 1856 killed 2000 prairie buffalo, as well as thousands of mountain sheep, coyote, and timber wolves. Their carcasses were simply left on the prairies to rot. His trip took him into Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, and the Dakotas. Along the way he shot at just about everything that moved with his 75 rifles and more than a dozen shotguns.

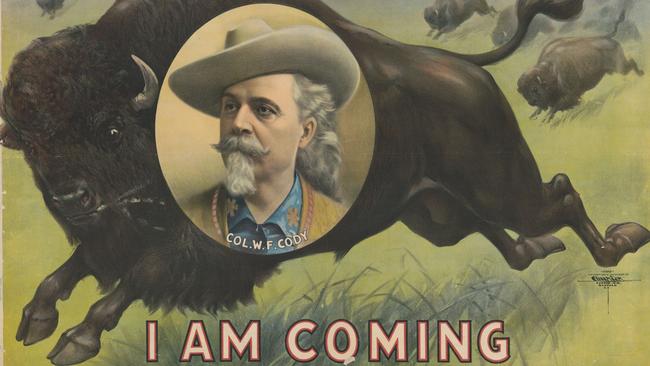

William Cody makes an appearance, hired by the Kansas Pacific Railway to kill buffalo to clear a pathway for the tracks and to feed the workers. He became known as “Buffalo Bill” Cody because he was so good at it, lionised in dime novels.

As always, the photographs, set to subtle motion, impressionably capture moments in time, allow us to slow down and think and reflect. But there are many that disturb, especially those of piles of rotting buffalo corpses that make their way into many of the scenes or the towers of skulls reaching to the skies often with hunters perched high on them.

The modern interviews, the voice over, and the mixing of still images with motion picture footage is smooth and seamless. Burns and his many collaborators immerse us in his aesthetic, developing characters and arranging details around their stories. And then there is the music, thematic melodies on fiddle, guitar, and mandolin, infusing the story and inspired by the landscape.

Professional historians still scorn Burns’s work. They see the films, the immense series, as too elegiac, not enough professional historians among the talking heads, his positions generally too centralist, and remain largely immune to the so-called Burns “magic”. He pulls critical punches, they argue in high disdain, and leaves out more extreme points of view. He’s just a middlebrow populariser, obsessed with putting through his many shows about American disappointment into the record.

“We are delighted to see so many people interested in the past, of course, but we tend to view the documentaries themselves as little more than historical melodramas, long on misty nostalgia but short on critical analysis,” historian David Harlan says.

The fact is they really can’t abide the way he tells such good stories, and how they have become such an important part of the making of history.

The American Buffalo streaming on SBS On Demand.