Stephen Sondheim musical paints a picture on love and the art of living

STEPHEN Sondheim's musical about a famous painting holds a lesson.

EVERYBODY knows Stephen Sondheim as the bloke who wrote Send in the Clowns, plus a bunch of far less sentimental songs for shows so obscurely cerebral they make the brain sweat.

It's all I knew about him until 2007, when I reviewed a broadcast of Sondheim in conversation with Jonathan Biggins for The Weekend Australian. Intrigued by what he said about his stories of the human condition, I asked a Sondheim admirer, Sydney actor Warren Jones, to tell me the backstory.

The shows he explained and the songs he described signed me up to Sondheim, which is why I am intrigued and excited to be seeing the Victorian Opera's production of his Sunday in the Park with George, which opens in Melbourne this weekend.

Because Sondheim is a storyteller of extraordinary imagination. He dissects humanity, with our obsessions and aspirations, loves and fears, lusts and follies, through characters who are variously engaging, appalling and appealing. And even with the big ideas, his work is great fun.

"The unfortunate thing is that people assume Sondheim is art, not entertainment," Stuart Maunder, who directs the VO production, says.

His creations aren't your average high school musicals (although it seems just about everybody in theatre who can sing played in Sondheim at school). He creates novels with songs, plays with music, a genre he did not invent but certainly transformed.

"Sondheim started at the end of the golden age of musicals. People thought the genre peaked with West Side Story, for which he wrote lyrics, but in the 70s he re-imagined musical theatre," Jones says.

"Sondheim kept musical theatre alive for four generations," Maunder agrees.

But he did more. He "re-imagined the genre", as Jones puts it. "People saw him as cold and heartless, an understandable attitude for anybody who grew up with shows which wore hearts on sleeves. But Sondheim said there was more, that musical theatre could do what Pinter and Stoppard were doing."

As in all his shows, there are songs in George that explain aspects of just about everybody's life (certainly mine), generally in confronting ways.

Many consider it his masterpiece. "It's a once in a lifetime opportunity to see a great work," says Alexander Lewis, who plays George. It's a work that even the acutely critical Sondheim once conceded has a first act "as good as anything I've seen in the theatre".

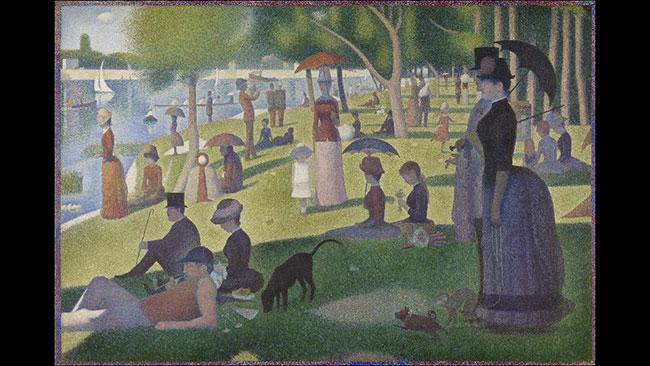

The show is based on Georges Seurat's famous pointillist painting, set in an island park in the Seine A Sunday on la Grande Jatte (1884). It is a remarkable work that captures Belle Epoque Paris, an era of elegance between the past humiliation of the Franco-Prussian War and the future horrors of World War I. "I defy anyone to say they have never seen the painting," Maunder says.

But while easily remembered for its beauty, the pointillist technique Seurat developed in the painting was devilishly difficult, requiring myriad tiny brushstrokes in contrasting colours. One of the strongest songs in the show, Finishing the Hat, is about the obsession required to complete just one element of the painting.

"We all have a specific moment in the show that relates to us as a true artistic experience and Finishing the Hat is the moment that resonates with me," Lewis says.

The first act is about Seurat and the people around him as he spends Sundays in the park obsessively painting a fashionable young woman while ignoring the girl in the dress who is modelling, his lover Dot. According to Christina O'Neill, who plays Dot, "She understands this but wishes it was different. She can't accept that he will not let her into his life."

George will not, or cannot, make room for Dot in his interior life, and she is bewildered that neither her sexual power nor her willingness to become whoever George wants can seduce him. But he is less cruel than incapable of accommodating anything other than his work, just as he will not crumple before the criticism of his revolutionary painting.

For me, George is one of Sondheim's solipsistic successes, a character demonstrating what self-obsession can do, for good and ill. George looks at life and chooses art. Maunder does not agree, arguing George speaks to us all. "Whether we are butcher, baker or candlestick maker, we all think of ourselves as artists," he says.

However, whether you admire George or empathise with Dot, there is no doubting that Sondheim and James Lapine, who wrote the book, created a psychologically complete work about the failure of individuals, ordinary and artistic souls both, to be open with each other. "It is about love and people trying to connect," O'Neill says.

And that's it - a beautifully constructed story of failed love and overwhelming obsession featuring one of Sondheim's greatest songs, We Do Not Belong Together, cruelly familiar to everybody who has lamented an inevitably lost love.

And that looks like it, with the cast singing Sunday, which describes the way George's obsession with light has made his painting and shaped their lives.

Except it isn't over. One of Sondheim's tropes is to present a self-contained story, only to add an entirely new dimension in a surprising second act. On a first listen to the soundtrack of his fairytale Into the Woods (with the best song ever about being a witch), it is difficult to grasp that the show has a second act that turns the first one on its head.

George also has a second act, which explores the same themes a century later in the US. While Sondheim is not one for happy endings, this has an optimism, of sorts, while making a poignant point.

"There is something about its composition; the way Sondheim sets it out is moving and vulnerable. It will be a struggle to get to the end of the second act, it is such a moving piece," Lewis says.

And so it is, but while the need to connect with love and family, life and work infuses all Sondheim's work, George is utterly original. After West Side Story Sondheim had a string of hits, notably my pick for his masterpiece, Sweeney Todd (Johnny Depp is fantastic in the movie version). But success soured with Merrily We Roll Along (1981), which closed after 16 performances. It is hard to understand why. With Company (a single bloke defies his married friend's expectations of how he should live), Merrily presents Sondheim's strongest songs about creative people comfortable in affluent America. Perhaps it was too scarily familiar for Broadway audiences because the tastemakers loathed it. "People were gleeful that it failed; Sondheim was badly burned," Jones says.

Eighteen month later, he less replied to than overwhelmed his critics with the lyrics and music for George. Significantly, George is a show about an insider sticking to his creative guns.

A serious subject to be sure, but blessed with beautiful songs about love and loss and ultimately the power to make our own lives.

The songs are glorious indeed; reason enough to see the VO's production. "Go and see George for the breathtakingly beautiful music," Jones says. "It is a once in a lifetime opportunity to see a great work," Lewis agrees.

And unlike most musicals, it combines beauty with art and adds a life lesson. "Sondheim explains you need to get out and do it - to move on," director Maunder says.

Not that I needed convincing. I can hardly wait.

Victorian Opera's production of Sunday in the Park with George, today to July 27, at the Playhouse, Arts Centre, Melbourne.