Review, Ethan Hawke’s A Bright Ray of Darkness

As this ‘fictional’ famous film star prepares for the most stressful role of his life, he is dumped by his even more famous rock star wife, with whom he has two young children.

Set in New York, where the Oscar-nominated actor and screenwriter lives, it centres on a 32-year-old film star who is making his Broadway debut. He has been cast as Sir Henry Percy aka Hotspur in Shakespeare’s Henry IV (as was then 32-year-old Hawke in 2003, though it was not his Broadway debut).

As this fictional famous film star, William Harding, prepares for the most stressful role of his life, he is dumped by his even more famous rock star wife, with whom he has two young children. He’s been caught, in the tabloid media, fooling around with other women while on set in South Africa, making another blockbuster.

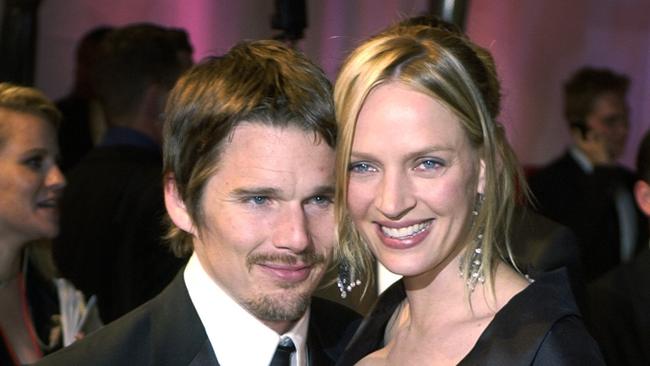

In 2003, the real famous film star about to play Hotspur separated from his just-as-famous film star wife, Uma Thurman. His infidelities were cited. They had two young children. It’s difficult, therefore, not to read William’s thoughts without thinking of his creator.

“Coming back to New York,’’ he thinks on arrival at JFK Airport, was like placing my head in the center of a well-made noose.” He checks into the Mercury Hotel, drinks, takes drugs, chases women, sees his kids and reads Shakespeare. His wife announces a new round of gigs, the Piss on Your Grave Tour.

However, for this reader, it’s not the possible links to Hawke’s own personal dramas that are most intriguing. It’s the discussion of moving from film to the stage and working with a great, demanding theatre director and a great, condescending theatre actor, the real star of the show, who is Falstaff.

Here’s the director, JC Callahan, addressing the cast on day one. “There are only two kinds of Shakespeare productions: ones that change your life, and ones that suck shit. That’s it. Because if it doesn’t change the audience’s life... the production has failed.”

Having stunned the actors into silence, he continues: “We’re going to come down on this city like God’s f..king fist and do the greatest American Shakespeare ever.”

JC is in his 60s, bald and wears bow ties. Look up photographs of Jack O’Brien, who directed Hawke in Henry IV.

Any reader will wonder how much of what happens is true, and will also do their own casting. There’s a hilarious scene when an older film star, who is even more famous than William, and perhaps madder, arrives in his limo and takes the younger man out to dispense some advice, and some cocaine, which he has in a Tardis-like bag. I have an idea of who this might be, but best not say so in print. Other readers will come up with other names.

Then there’s the moment when William is in a bar, trying to memorise Hotspur’s opening soliloquy, and he meets Eugene R. Whitman, “America’s greatest living playwright”. The winner of two Pulitzer prizes is drinking heavily and chatting up a woman about 40 years his junior. “My hero,’’ William quickly realises, “was blitzkrieg drunk”. Again, some names popped into my head.

Yet it is Falstaff who is the most fun to think about. It’s fascinating to read of the hierarchial nature of stage acting, even if it’s assumed and not stated. Virgil Smith is an Oscar winner, a Tony winner, “probably the only legitimate American film star who was also a universally celebrated and respected theater actor. He was everything I’d ever wanted to be, since I was old enough to want”.

When they first meet, William thinks, “since I was kind of famous and he was superfamous, I guess he figured we should hug”. Virgil is arrogant but not unkind. He advises his Hotspur to work on his consonants, especially “your t’s and d’s”, and adds that overall he would be better off with Chekhov, “who gives the actor the leaves — and we must build the tree”. Shakespeare, on the other hand, “provides the whole tree — only the leaves are ours’’.

This can only be a nod to Hawke’s real Broadway debut, in 1992, as Konstantin Treplev in Chekhov’s The Seagull. That’s amusing, but the overwhelming question is who is this Falstaff? It was Kevin Kline in Hawke’s real life, but I don’t think it’s him. Several names popped into my head — remembering the actor must be American — before I settled on one I am confident about: Al Pacino. I think The first Godfather movie is alluded to.

This is a very funny, very well-written novel that can be read on several levels. The title, by the way, comes not from Shakespeare but the Bible. The novel’s final Act (rather than Chapter) starts with this quote from Psalm 139:12: “The darkness is not dark to you; the night is as bright as the day, for darkness is as light.”

I think the haunting final lines of the novel speak to this, but I may be wrong. Perhaps it’s relevant to a bit early on, when William understands there can be dark and light at the same moment: “Everyone hated me so much these days, I was sure a spectacularly humiliating Broadway failure would please the world immensely.”

-

Yes, I am back. Yes, that means I did not win Lotto in the past month. Yes, I know I’ve said that before but it remains true. I want to start 2021 with a recent novel that has mental health at its heart: Meg Mason’s Sorrow and Bliss (4th Estate, 346pp, $32.99).

Mason is a New Zealand-born, Sydney-based journalist turned author. The novel is set over 2017 and 2018 in England, where the author lived and worked for the Financial Times. This is her third book, following her 2012 motherhood memoir Say It Again in a Nice Voice and her 2017 debut novel You Be Mother.

The main characters are Martha, an acerbic 40-year-old journalist who writes a “funny food column”, and her sister Ingrid, who is 15 months younger. Martha is married to Patrick. They have no children, for reasons that will become heart-rending. Ingrid and her husband Hamish have children, regularly. As the novel opens Ingrid is pregnant with her fourth child.

The sisters’ father is a poet. When he was 19 his first poem was published in The New Yorker and someone described him as a “male Sylvia Plath”. Their mother, a “minorly important” (according to The Times) sculptor, was his girlfriend at the time. She allegedly asked: “Do we need a male Sylvia Plath?” Though she now denies having said that, “it is in the family script”. Their father has been working on a book of poems ever since.

Martha’s relationship with each of her parents, who live in a bohemian mess at Shepherd’s Bush, becomes important as the story develops. Fans of the TV series Fleabag may see similarities.

Martha is the narrator and the novel opens after she and Patrick have split after eight years of marriage. As we learn the histories of each character, we understand that Patrick has been in love with Martha since their childhood. However, her first, short marriage was to “Jonathan F..king Annoying Face”, as her sister called him.

Martha remembers, at “a wedding shortly after our own”, talking to another woman, someone she does not know. She recalls telling her that Patrick was “sort of like the sofa that was in our house growing up”. She continues, “Its existence was just a fact. You never wondered where it came from because you can’t remember it not being there. Even now, if it’s still there, nobody gives it any conscious thought.”

Soon after, thinking to herself, she decides that “an observer to my marriage would think I made no effort to be a good or better wife”. Yet what that observer could not know is “that for most of my adult life and all of my marriage I have been trying to become the opposite of myself”. This is the first strong hint that Martha suffers from mental illness. The author does not name the illness. I think she does not want her character — or people in the real world — to be defined by words such as schizophrenia or bipolar.

As the novel progresses, weaving between archly comic moments of ordinary life and deep, dark places in one woman’s unordinary life, readers will make their own diagnosis. They may think of the aforementioned Sylvia Plath, or of Virginia Woolf, who Martha reads from start to finish at one point when she moves back in with her parents. As she peruses her father’s library she decides on a threefold selection criteria: “books by women or suitably sensitive/depressive men who had made up their own lives [and] any book I had lied about reading”. There is a wryly funny caveat to the third: “except Proust because even with everything I had done I did not deserve to suffer that much”.

This is one of the best novels about marriage that I have read, and that is a large field. When Martha thinks of breaking up with Patrick on their fifth wedding anniversary, which they are spending in Venice, she sees him in bed, marking up a Lonely Planet guide to the city: “as ill and as scared as I was, I couldn’t bear to disappoint someone whose desires were so modest they could be circled in pencil”. What a sadly beautiful image that is.

This is also one of the best novels about mental illness I have read. As we learn about each of the characters, we feel closer to Martha, in a sympathetic sense, and we feel further from her, repelled by her. It is her sister and her mother who are the straight talkers; the first from the outset, the second later on, in an explosive outburst of honesty about her eldest daughter and about herself. She tells Martha that she has no idea what her husband wants, and has never tried to have any idea.

“Sometimes I wonder if you thought it was going to be easier to just blow everything up. Tip, tip, tip, kerosene everywhere, match over the shoulder as you walk away. Incinerate the lot.” Then her mother talks about herself in a way she has not before. It is here that we perhaps have answers to questions we have been asking for much of the book.

I read Sorrow and Bliss this year but I am adding it to my list of the best novels of 2020, alongside Andrew O’Hagan’s Mayflies, Sofie Laguna’s Infinite Splendours and Douglas Stuart’s Shuggie Bain, which won the Booker Prize.

Ethan Hawke’s fourth novel, A Bright Ray of Darkness (William Heinemann, 256pp, $32.99), is tantalisingly autobiographical.