Something to crow about

A cross-cultural bromance between an Adelaide historian and his Mongolian translator puts a fresh spin on Australia-China relations.

When in August 1962, Li Yao set off from his village to enrol in Inner Mongolia National University, the bookish 17-year-old had fried oatmeal (a Mongolian staple) and steamed buns in his luggage and the dream of becoming a writer in his head. IMNU wasn’t a top-tier university, and the Party had deemed that he would be studying English, not Chinese, as he’d hoped. But Li, who had a landlord grandfather and other “bad elements” in his family, knew he was lucky to be getting a higher education at all.

The Cultural Revolution began four years later. Its storms buffeted Li and his family. But he survived, and Australians have reason to be grateful. Thanks to some unpredictable career twists and a random gift of a Patrick White novel, Li is today the premier translator of Australian literature in China, with almost 40 books to his credit.

David Walker, like Li, was born in 1945, the year of the Rooster. He grew up in South Australia, at a time when not even Australians took Australian writing very seriously.

While Li was poring over Pride and Prejudice in the Inner Mongolian capital of Hohhot, David, a history major at the University of Adelaide, was searching for Australian texts among the predominantly British and other volumes in his state library’s history section.

Later, as Walker worked on his PhD at the Australian National University on the “search for Australian cultural identity”, Chinese people his age appeared a mass of fanatical hysterics, waving Mao’s Little Red Book and burning others. If you’d told him that one of them might devote his career to translating the likes of Henry Lawson, Patrick White or – most fantastical of all – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander writers – and that that person would become one of his closest friends, he’d probably have thought you mad.

Happy Together is a cross-cultural bromance, a richly textured double autobiography, a travel memoir, and a quest for identity.

Along the way, it illuminates two very different nation’s distinct paths to modernity. Rendered with the historian’s eye for deep story and the translator’s feel for cultural texture, it is a complex and deft weave of a book. Frequently moving, sometimes funny, occasionally corny, it is unfailingly absorbing.

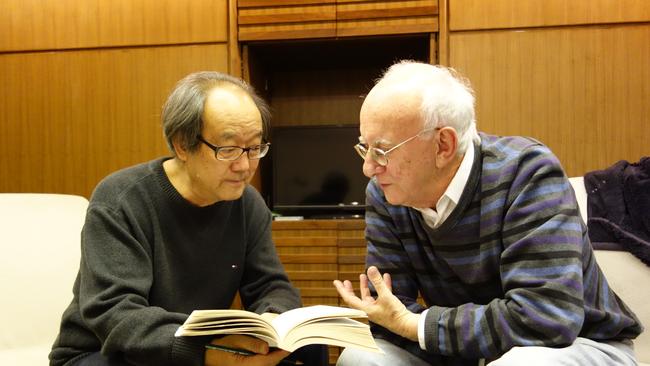

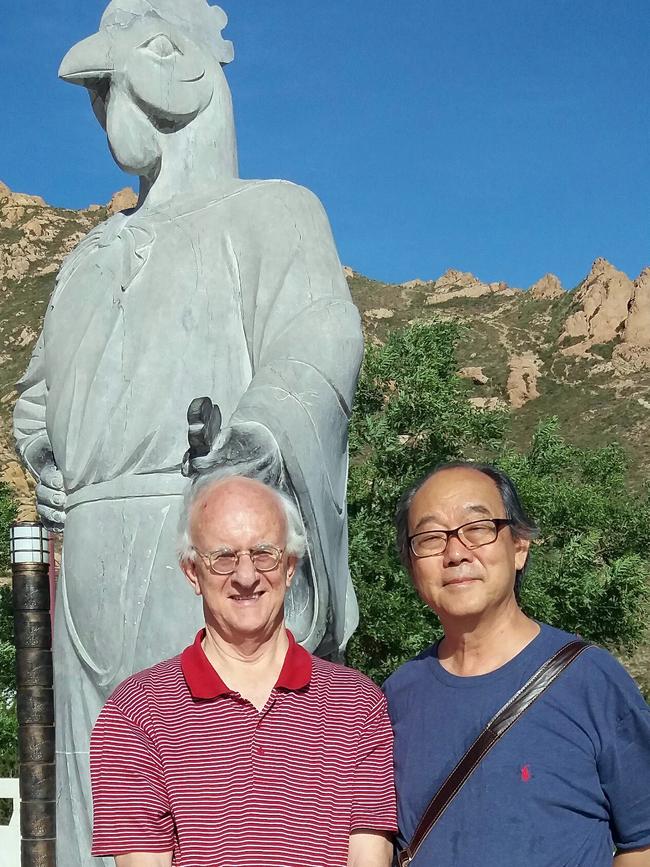

The “two roosters”, as Li and Walker refer to themselves, explore difference while seeking resonance. They find this in aspects of their families’ stories, the vast open landscapes they knew as boys, their senses of humour, and keen interest in history and literature. They share amazement at their own good fortune: the boy from the “bad class background” now the celebrated holder of an honorary doctorate from two Australian universities, the other the mischievous boy whose high school aptitude test pointed to a reasonable shot at a job as a wool classer, now a professor and doyen of Australian Studies.

The pair met in 2012. Li was preparing to translate one of Walker’s books, and Walker was about to settle in Beijing for three years as the BHP chair of Australian Studies at Peking University. They began a close and generous friendship. Their curiosity about one another’s lives and backgrounds presents the reader with detailed and intimate vignettes of life in both Australia and China – though Li’s more dramatic story understandably dominates.

One of my favourite anecdotes describes the time Li, as a young reporter, was sent to cover the story of an Inner Mongolian woman lost in a snowstorm while herding the commune’s sheep. Her desperate mother had gone searching for her. Both suffered frostbite; the mother lost a leg. Li’s touching story of mother-daughter love didn’t make the grade. He watched as another journalist re-interviewed the semi-literate pair, asking leading questions about the role of Mao’s wisdom in their survival. The rewritten article, splashed across the front page of the Inner Mongolia Daily, turned the pair into revolutionary heroes for being inspired by Mao to risk their lives guarding state property (the sheep).

Relations between Australia and the People’s Republic of China haven’t always been an easy ride. Today, they are more deeply strained than at any time since the normalisation of diplomatic ties 50 years ago, including 1989. Serious, even grave challenges lie ahead as China’s aggressive military signalling to Taiwan intensifies, and we are forced to deal with such incidents as that of a Chinese fighter jet’s interception of an RAAF surveillance plane over the South China Sea in June.

It’s not the purpose of Happy Together to provide critical analysis of the bilateral relationship or its politics. It is a timely reminder, however, that as people we will always have more in common than our differences suggest. It is also an admonition, as the authors write on its final pages, that “Listening is both an act of courtesy and a way of learning.”

Happy Together: Bridging the Australia-China Divide

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout