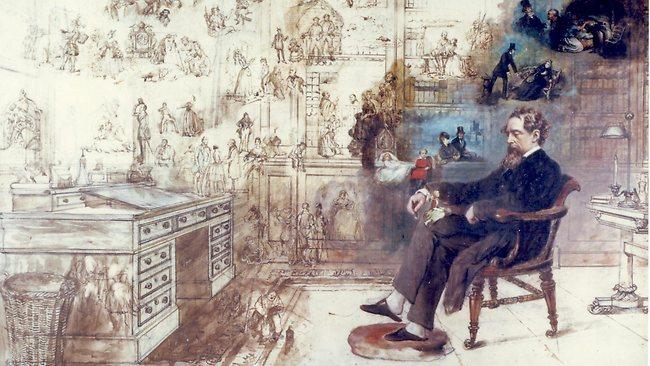

Solitary giant of literature, Charles Dickens

TWO new biographies of Charles Dickens are timed to celebrate the bicentenary of a writer second in line only to Shakespeare.

CHARLES Dickens's ascent to the sharp end of the canon, where he now stands elbow to elbow with Shakespeare, has been neither smooth nor assured. There have been moments since the author's death when his multifarious works looked set for history's dustbin.

The man was inseparable from the Victorian era he lived through, with its taste for sentimentality and melodrama, its death-fetishes and sexual taboos. Dickens didn't just bear witness to this age of social and economic extremes in a nation drunk on industry. He helped create the structures of feeling against which subsequent generations would rebel.

Conrad's novels, Shaw's plays, and Lytton Strachey's brutally witty biographies all worked to tear the lace from the lampshades of the Victorian worldview. Their modernist successors blew the whole balustraded edifice sky high. It was a shift in literary taste so total that, in 1939, critic Edmund Wilson could fairly report "of all the English writers, Charles Dickens has received in his own country the scantiest attention from either biographers, scholars, or critics". When Bloomsbury did deign to notice him, Wilson continued, it made Dickens "into one of those Victorian scarecrows with ludicrous Freudian flaws - so infantile, pretentious, and hypocritical as to deserve only a perfunctory sneer".

Of a slew of works about the man and his work timed to appear for the bicentenary of his birth, two English biographies - Claire Tomalin's Charles Dickens and Robert Douglas-Fairhurst's Becoming Dickens: The Invention of a Novelist - are exemplary instances of a stunning turnaround in Dickens's reputation.

If we date the founding of modern Dickens studies to Edmund Wilson's essay The Two Scrooges quoted above (giving due credit to George Gissing and G.K. Chesterton, who kept his flickering flame in earlier years), then the seven decades since have seen an expansion of interest in the author almost without precedent.

What happened between then and now? It was the discovery, as Angus Wilson wrote in 1970's The World of Charles Dickens, "that Dickens, with his extraordinary intuition, leaps the century and speaks to our fears, our violence, our trust in the absurd, more than any other Victorian writer".

Biography has been crucial to this reappraisal. Painstaking efforts to disentangle the author from his myth have led to the emergence of a very different Dickens: a less ideal specimen, certainly, but one whose flaws are magnetically human. We have discovered a man whose immense capacity for kindness did not extend to those closest to him; a dreamer with a shrewd eye for the bottom line; a sentimental comedian; and an industrious playboy. For all his gregariousness and fame, he emerges from these biographies a solitary figure. He stands apart, not just from his intimates, but also from the public whose adulation he sought.

The task of demythologising Dickens begins early, with the vast biography undertaken by his best friend and literary executor John Forster. His exhaustive The Life of Charles Dickens, published in the years immediately after Dickens's death (and recently reissued by Oxford University Press), is often a pompous and reverential account. But it is not unperceptive or uncritical. Forster admired the writer as a genius. But he saw the human wreckage left in the wake of those magnificent literary labours.

Dickens's imaginative constructions were a failed flight from the world, he observed. The control-freak novelist could impose order on his fictional creations. He could bind characters to his will; everyday life was more stubborn and less malleable. Dickens, wrote Forster, "had not in himself the resources that such a man, judging from the surface, might be expected to have had":

Not his genius only, but his whole nature, was too exclusively made up of sympathy for, and with, the real in its most intense form, to be sufficiently provided against failure in the realities around him. There was for him no "city of the mind" against outward ills, for inner consolation and shelter.

Dickens's friend quoted extensively from their correspondence. And while he writes only briefly of the end of Dickens's unhappy marriage to his wife Catherine, who bore him 10 children -- a cruel, public break engineered by the author (in cahoots with Forster, who drew up the legal papers) -- he made public the signal event of Dickens's childhood: a period spent working in a blacking warehouse when he was 12, after his father's debts had sent him to Marshalsea prison.

It is impossible to overstate how scarifying an experience this was for Dickens. His time spent lettering labels for boot polish was a humiliation that never faded; a goad to achievement that never failed; and a sympathetic education in ordinary life that stayed with him, even in the midst of wealth and success.

Every subsequent biographer of the author has returned to Forster's Life and mined it for data. But the other significant event in Dickens's biography is not to be found there. It was not until Edgar Johnson's magisterial mid-century Dickens: His Tragedy and Triumph that most readers learned of Ellen "Nelly" Ternan, the young actress with whom the author maintained a semi-secret relationship for the last 12 years of his life.

The American biographer's scholarship was wide-ranging and impeccable. So when Johnson's Dickens turned out to be a radical firebrand, hostile to the iniquitous society of his day - as well as a man who kept a mistress - readers accepted that their cosily familiar author would now on be seen in a new light. Those who came after, from Norman and Jeanne MacKenzie to Peter Ackroyd, refined and deepened this sense, of a darker and more damaged Dickens: one whose humanitarianism was distinct from the dull civic-mindedness we associate with the Victorians.

It was Tomalin, in 1991's The Invisible Woman, who used the available material to the most startling ends. Her biography inverted the usual process, by which Ternan (and other female satellites in Dickens's life, including his wife's sisters, Mary and Georgina Hogarth) were kept to the domestic sidelines. Instead it placed this much younger woman (Dickens was 45 when he met Ternan; she was 18) at the story's heart.

Tomalin's account was widely praised for its combination of research and imaginative reconstruction: a necessary fusion, since the women in Dickens's life were neither observed nor recorded in the same way as their male counterparts. If it did not settle once and for all the nature of the most important relationship in Dickens's later life (whether their affair was consummated, or even sexual in nature, remains contentious), the biography made visible the experiences of women who, with varying degrees of talent and success, carved out independent lives for themselves in a pre-feminist era.

Her new attempt at a life of Dickens is more traditional. It places the writer at the centre of events, though Ternan remains the most important person in his later years, and introduces little in the way of new material, aside from revisiting the fascinating hypothesis (first advanced in the paperback edition of The Invisible Woman) that Dickens collapsed in compromising circumstances, and had to be spirited back to his home in Kent, where he died.

Tomalin's genius for synthesis means she covers a furious amount of ground in little more than 400 pages of text, all the while bringing novelistic colour to portrayals of Dickens and his world. Her readings of his work are brief yet acute, and her responses to the man are sympathetic but not reticent when criticism is required.

The result, unsurprisingly, is a finely balanced appraisal. Every time the rising author stiffs a publisher or rewrites a contract in his favour, Tomalin finds a counter-story of Dickens's generosity to needy strangers. For each gallant gesture or statement of fraternal feeling there is a corresponding withdrawal of intimacy, or a frosty domestic anecdote. The ledger is totted up in such a way as to confuse our impulse to damn or praise Dickens, and this is presumably the point. Dickens is typical of his time in having a double life. But he is untypical in resisting our ability to render him a simple hypocrite.

Tomalin is equally fair and proportionate in the way she tackles Dickens's protean existence throughout the years. She touches briefly on each of the salient events of his childhood (raising the not inconceivable possibility that John Dickens, the author's father, was a child of a liaison between a servant in the house of Lady Crewe and the playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan): the golden early years, followed by a move to London and the family's descent into poverty and his subsequent time as a child labourer.

She marches swiftly though his minimal schooling and years as a legal clerk and parliamentary reporter, though she slows to examine his youthful love of the theatre and his apprentice writing efforts, culminating in the 1836 appearance of Pickwick Papers, when Dickens was still in his early 20s, that marked his arrival as a writer.

Most think of the subsequent trajectory of Dickens's life as a smooth, unbroken arc towards becoming the most famous writer in the world: a phenomenon, even an adjective. Tomalin shows that his course was more jagged. There were money problems during the economic downturn of the 40s - it was not until serial publication of Dombey and Son began in 1846 that his finances stabilised - and an ever-increasing army of family and friends to support.

His health suffered under a regime of massive workloads interspersed with regular late-night carousing. He smoked and drank heavily too (though he went riding regularly, danced energetically, and thought nothing of walking 10, 20, even 30 miles at a go).

The relative brevity of Tomalin's account means that every book, trip, theatrical reading, birth, death, and new publication must be treated with strict economy. On occasion, though, the biographer allows herself an excursion. Special attention is given to those instances where Dickens came to the rescue of a woman or women in distress. As a public advocate for reform he was eloquent and impassioned, but he was never so hands-on as when, say, a distant acquaintance died, leaving his wife and children penniless. More astonishing than Dickens's immediate practical assistance and generosity, is his long-term commitment: many of these wives and children were still in contact with him decades afterward. The chapter devoted to his work in founding a house for fallen women speaks volumes about the ways in which the author sublimated his sexual drives into aid and succour.

Evenhandedness is not always a virtue, however. It certainly wasn't one that Dickens possessed. Tomalin provides us with an intelligent, entertaining and broad overview of her subject from alpha to omega whose only weakness is that it is obliged to keep to the middle of the road.

Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, a brilliant young Fellow at Magdalen College Oxford, has taken a different track. His Becoming Dickens leaves off at point where the young sketch-writer known as Boz starts publishing under his own name. It ends where most biographies start to find their pace.

Douglas-Fairhurst has thought carefully about the chief problem facing the Dickens biographer today: namely, that all primary materials on the subject have entered the public realm. Barring some remarkable discovery, the letters have all been published and the author's single undestroyed diary found. Each new Life, then, is a restatement, with differing angles of inflection, of the same evidence. What links the many biographical accounts of Dickens's life is their assumption of the inevitability of the author's emergence; their sense that his genius was so profound, his determination so great, that he would have overcome any impediment to become the inimitable Charles Dickens.

Not necessarily so, argues Douglas-Fairhurst, who points out Dickens's works are haunted by the sense that his destiny could easily have been other than it was. Take David Copperfield. When Dickens opens with the line: "Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show", the biographer argues he "sets the scene for a novel that is full of speculation about how many possible lives are contained within each human life".

This elegant and intriguing thesis is pursued through Dickens's early years: a period when, in Douglas-Fairhurst's words, "the young man tried on several jobs for size, including actor, stage manager, journalist, and clerk. At one point he even considered emigrating to the West Indies." The counter-factual task of the biographer is, then, to follow the traces of these alternative lives in Dickens's fiction.

The result is an anti-biography that feels closer to the texture of Dickens's experience than many more expansive efforts, and one that gets closer to the enigma of his achievement. Dickens was loved in his own time for visions of domestic felicity, achieved in spite of drama and discord, that seemed to offer earthly reward for goodness. Douglas-Fairhurst shows convincingly how these happy endings were powerful inasmuch as they reflected the intensity of Dickens's wish-fulfillment.

Today, though, it is his dark shadows readers respond to: the paupers, drunks, con-men and criminals who bodied forth Dickens's lifelong fear of failure.

Charles Dickens: A Life

By Claire Tomalin

Viking, 527pp, $39.95

Becoming Dickens: The Invention of a Novelist

By Robert Douglas-Fairhurst

Belknap Press, 389pp, $40.99

Geordie Williamson is chief literary critic of The Australian.