Silver lining in John le Carré’s posthumous novel Silverview

What are we to make of this bald, simplified bit of fiction that has emerged a year after the spymaster’s death?

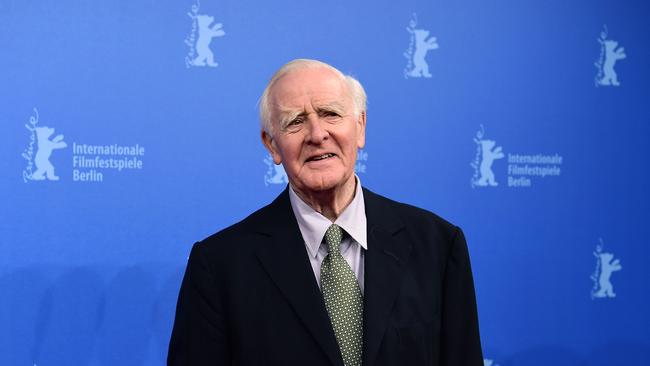

The publication of this posthumous novel by John le Carré is a reminder of the intense pleasure he gave us over 60 odd years. He’s the author of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, that most poignant of Cold War thrillers where the higher trash seems in danger of turning into something darker and more real. And of the Smiley novels where a masterspy of all but saintly tranquillity takes on a world of cutthroat treachery and infinitely divisible loyalties. It helped that Richard Burton gave one of his best performances as Leamas the heavy drinking anti-hero in the film of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold and that Alec Guinness as Smiley in the ITV version of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy transfigures his character so that David Cornwell (the author’s real name) said he realised he was writing a character the great actor had extended and revised. The best introduction to le Carré is in fact to watch a snippet of Guinness in Tinker, Tailor or its successor Smiley’s People. At some point, le Carré lost his primary subject when the Berlin Wall came down but he remained an incomparable entertainer and his highly accomplished yarns were forever lapsing into approximations to art as in the extraordinary portrait of his conman Dad in The Perfect Spy or the veils of self-reflexiveness in The Little Drummer Girl refurbished and revamped for television with Florence Pugh as was The Night Manager with Hugh Laurie, a great improvement on the original novel. So if le Carré was always open to improvement because his genius was so intrinsically dramatic what are we to make of this bald, simplified bit of fiction that has emerged a year after his death? It’s schematic, it’s cluttered, it lacks air and development but there’s enough of the old enchantment, the power to visualise, the power to divert, to fascinate and reward.

There’s a middle-aged witch hunter with a mild manner, easy to underestimate with a sidelong smile slightly reminiscent of Smiley and a figure of interest with just a remote hint of a middle European cadence who has had his apparent moments cheering for the Other Side but also doing obeisance to the Service. There’s his beautiful dying Arabist wife who has been a master of secret arts and a manner of such riddling composure and authority that we’re hooked from the start. There’s an Irish lady whose Trinity College skills are overtly dedicated to archaeology and a Manchester broad who becomes a halfway house for high and mighty (Ming or whatever) blue and white treasures.

And then, a bit improbably, right at the centre of this half-ruined jigsaw puzzle of a book in which the parts don’t quite add up, there’s a bloke formerly from the City, thirties, who knows nothing about books – not WG Sebald, master of the essay as fiction, not Noam Chomsky with his deep structures and political radicalism. He somehow falls into the hands of the Middle European mystery man who went to school with his former vicar, then atheist, Dad and adored him.

They set out together to run a bookshop that will have a strong line in literary classics.

The fabled home that looms over the book is a nod to the German villa Nietzsche spent his final years in: Silverview translates Silberblick.’ It’s a typical let’s go nowhere-for-the-sake-of-it touch in this haunted hulk of a book.

Things are helped along a lot in Silverviewby the fact that the daughter of the dying woman is a bit of a delight. Boyish hair, indecorous, she talks an utterly credible argot that seduces the reader and makes her thankful that the magister ludi, the master of this particular fictional game, should have been visited by a vision like this in the last days of his writing life.

Was it a crime against Cornwell’s masterliness to publish this draft which is not quite a fragment in the way his executors have? No, because there is enough of the old enchanter here to be getting on with even if the momentum and the variation, the command of tension and relaxation are in wild misalliance in this last sketch of a book.

It’s worth remembering that le Carré was almost always an imperfect writer and that he aspired, pretty successfully, to be a bit more than a literary artist because he had such a grip on the populaire.

What he embodied and carried to some kind of sunlit height was the paradox of highbrow trash. And even in one of the best of the later books A Most Wanted Man, filmed with Philip Seymour Hoffman – the one about the Germans and the Chechen – the writing is at its least successful when it’s at its most literary: we’ll enter the Scottish banker’s head and he’ll make a stump speech to highlight his sensibility. None of which necessarily gets in the way of le Carré’s readability though his books were always works in progress as the classics demonstrate by the superiority of the absolutely faithful dramatisations just as the elaborations of the lesser books do.

Silverview is an open provocation to elaboration. It is full of suggestive ideas as well as moments of irresistible realisation, as with the girl.

If the whole thing is a bit like the dream that summons up an acrostic simulacrum of a novel by the great spymaster that doesn’t matter because there is enough of a vision of the thing for the sorcerer’s apprentices to be getting on with.

Like its predecessor Agent Running in the Field, though in a less developed way, Silverview is a bit of a meditation on what makes a spy story and what reality can lie beyond the conundrum of the great game, as Kipling called it.

At his best, le Carré was a master of the mechanics of storytelling who combined an intoxicating sense of mystery (and a vertiginous complexity of articulation) with a deep and marvellous command of stereotypes that blended into archetypes – Jimmy Porter by the Berlin Wall, Father Brown gazing into the crystal ball of iniquity and mercy as he battled the KGB.

There are the novels that go haywire out of seriousness or sentiment like The Naive and Sentimental Loveror righteousness like The Constant Gardenerbut his stories are retrievable as the latest TV versions show.

And Silverviewis worth the fiddling with. There’s enough magic glimpsed here to make the journey.

Peter Craven is a cultural critic.

Silverview

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout